There are times when a major drama in the House of Commons really does change the course of British history. The period 1974–79, dramatised in the play This House, was one such. The crisis over the Great Reform Bill was another. Not so long ago, every schoolboy knew that the 1832 Reform Act gave the vote to the middle classes. Nowadays, thanks to the collapse of history teaching, very few schoolboys or girls know anything about it at all. Antonia Fraser has written a compelling and timely book on this almost forgotten political battle.

The story begins with the election of 1830, which was called because of the accession of King William IV. The Tories, who had been in power for virtually 60 years, scraped in with a flaky majority. The Duke of Wellington, the Prime Minister, declared in the House of Lords that he was utterly opposed to any reform of parliament.

Wellington, as Fraser writes, suffered from ‘the isolation which haunts the very grand’. He was a poor speaker, and he badly misjudged the public mood, which strongly supported reform. His government fell. The mob took to the streets, and Wellington ordered armed men to defend the windows of Apsley House. The Whigs, who had been out of power for so long that they seemed condemned to permanent opposition, took office. Lord Grey formed a minority government, pledged to the reform of parliament.

Academic historians have analysed the complexities of the unreformed voting system, with its rotten boroughs and medieval franchises. Fraser wastes no time going down rotten burrows (as 1066 and All That described them), but cuts straight to the chase of the parliamentary drama. And what a drama it was.

The hero of this book is the Whig Prime Minister Lord Grey — who is usually portrayed (at least in middle age, after his scandalous affair with Georgiana Duchess of Devonshire) as rather an old stick. Fraser brings him to life as no one has done before. A lifelong advocate of the reform of parliament, Grey was a tall, elegant 66-year-old with a splendidly domed bald forehead. He groaned when he was forced to uproot himself from his beloved Howick in Northumberland and trundle down to London by coach. But this was a pretence; he knew that Wellington’s fall gave him the chance he was waiting for. Like an old war horse scenting battle, he was energised by the crisis.

His government was one of the most aristocratic and nepotistic ever formed. Grey gave office to one son, three sons-in-law and two brothers-in-law, not to mention numerous cousins. But these Whig toffs proved to be unexpectedly effective reformers.

One son-in-law, ‘Radical Jack’ Lambton, Earl of Durham, was put in charge of the committee of four which drafted the Reform Bill. Spectacularly handsome but emotionally volatile, Durham was a spoilt, coal-rich posh boy. During the crisis his beautiful 13-year-old son — immortalised by Sir Thomas Lawrence in the painting of ‘The Red Boy’ — was slowly dying from consumption, and this made Durham mad with grief, and even more foul-tempered than usual. But, as Fraser says, his title ‘Radical Jack’ was well-earned, as it was his sulking and goading in Cabinet which kept Grey on course for reform.

In the Commons, the bill was introduced by Lord John Russell, a tiny man with a huge head: he spoke in a high-pitched voice with a stammer and an old-fashioned Whig accent. The Leader of the House, ‘Honest Jack’ Althorp, heir to Lord Spencer, another member of the Whig cousinhood, seemed a bovine character; addicted to bull-breeding, he was always threatening to quit politics for the country. But, as Fraser shows, he was (like many Spencers) cleverer than he seemed. He had a first-class degree in maths, and his role in pushing the bill through the Commons was crucial.

The bill passed the Commons by a majority of one vote in March 1831, but the government was defeated shortly afterwards. The King agreed to dissolve parliament, and the election returned a House of Commons which was overwhelmingly in favour of reform, but the House of Lords was recalcitrant. In spite of a brilliant three-hour speech by the bottle-nosed Lord Chancellor Brougham, heavily fortified by alcohol (‘perhaps the allusion to a bottle was justified’), the peers threw out the bill. The mob exploded into violence, and in the Bristol riots as many as 400 were killed.

To get the bill through the House of Lords, Grey needed to persuade the King to create peers. William IV features as a shadowy figure in most accounts of the crisis, but Fraser characterises him vividly, and she is right to do so, as the role of the monarch has been underestimated. Aged 66, William was anxious to do the right thing, apt to fall asleep after dinner and, being an uxorious character, inclined to listen too much to his younger wife, the 38-year-old Queen Adelaide.

The latter presided over a dull, puritanical court — ladies who wore décolletage were ‘told sharply to cover up’ — and she had strong political views. Reared in the tiny German principality of Meiningen in the shadow of the French Revolution, she was a German princess with a horror of reform and little grasp of English politics. Vilified for her Tory sympathies and German accent, Queen ‘Addle-head’ did indeed attempt to hatch secret plots with the Tories.

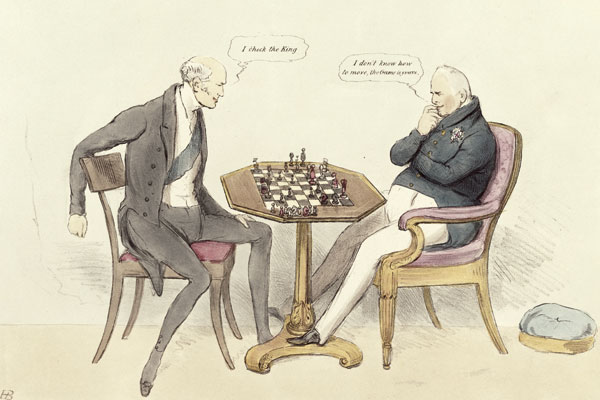

The final chapters of the book read like a thriller. The crisis came in early May 1832. Again, the House of Lords threw out the bill. But still the King refused to create peers. Would there be revolution? The demonstrations and uproar, orchestrated brilliantly by the radical tailor Francis Place, frightened the middle classes. The Duke of Wellington attempted and failed to form a government. Eventually the King gave way. Grey resumed office,William agreed to create peers, and the Lords passed the Bill.

Fraser gives credit for this firmly to Grey, whose strategy paid off. But this is not old-style, judgemental Whig history. On the contrary, it is a superb account of the human, as well as the political, drama. That a privileged elite could put its own house in order so effectively — cutting against its class interest — is a striking achievement by any standards.

The book should be required reading for today’s millionaire ministers who seem sadly lily-livered by contrast with Grey and his Whigs. This is history as it should be written: lively, witty and, above all, a cracking good read. I found it almost impossible to put down.

Comments