Lima, Peru

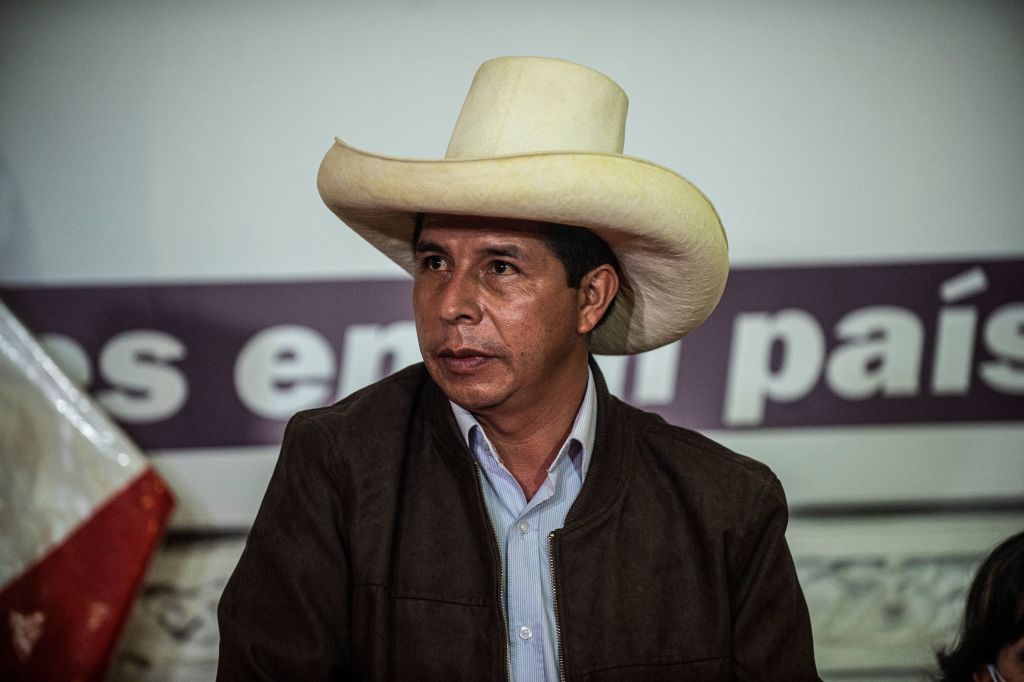

For the last 17 months, Peruvians have been wondering what it would take to see the back of Pedro Castillo, their staggeringly incompetent and deeply unpopular far left president.

On Wednesday, they got their answer — when Castillo made a botched attempt to metamorphise from an elected head-of-state into an even more inept version of that trope of Latin American history, the caudillo or authoritarian strongman.

Cornered by anticorruption prosecutors and facing an impeachment vote that evening, the 53-year-old former rural schoolteacher and wildcat strike leader decided to take the bull by the horns.

In an unannounced televised address to the nation shortly before noon, Castillo, his hands visibly shaking, declared that he was dissolving congress, restructuring the judiciary, imposing a national curfew and, for good measure, would be ruling by decree.

Normally, wannabe dictators confirm with the generals and admirals that they have the support of the armed forces before taking such a drastic and flagrantly unconstitutional step. Failing that, they might want to ensure that they have widespread public backing.

But not Castillo.

For reasons that have yet to become clear, but which almost certainly blend large doses of both desperation and a detachment from reality — from a president whose antipathy towards the free press led him to famously never read the newspapers — Castillo committed a miscalculation as glaring in its own way as Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine or Elon Musk’s $44 billion bid for Twitter.

The response to the authoritarian power grab was immediate and overwhelming. Condemnation rained down from everyone from the US Embassy and Castillo’s own lawyer to Peru’s Joint Command of the Armed Forces.

Lawmakers immediately brought forward the impeachment vote, which until that point had not been certain to achieve the necessary two thirds supermajority to oust the president. Less than two hours after his TV address, Castillo had been voted out of office with immediate effect by 101 votes to six.

The drama then turned to farce as Castillo, attempting to flee to the Mexican Embassy, became trapped in Lima’s notorious congestion. A SWAT team surrounded his black SUV and arrested the former leader.

Charged with ‘sedition’ and ‘rebellion’, he was interrogated by Peru’s chief prosecutor and spent his first night in the cells. Peru’s hard-charging judges may be unlikely to grant him bail and it could be decades before he is ever freed.

For most Peruvians, Castillo’s abrupt downfall could hardly be more welcome. He largely won the April 2021 runoff election by default, after facing off against Keiko Fujimori, the widely detested daughter of the jailed 1990s autocrat who faces her own corruption trial and potentially lengthy prison sentence.

In Peru’s splintered, dysfunctional politics, with more than a dozen equally unpopular parties vying to control the public coffers, just breaking into double-digit levels of support proved enough for these two deeply problematic candidates to face off against each other.

Once in office, Castillo quickly demonstrated that his stump messaging about being the president of the poor had been the empty posturing of a shallow populist who had previously proven incapable of even being elected village mayor.

Absurd campaign promises, such as spending 10 per cent of GDP on public healthcare and a similar amount on state schools, were swiftly forgotten. But so too was any genuine interest in Peru’s most marginalized citizens, the rural poor, who formed Castillo’s base.

With half of Peruvians experiencing food insecurity, double the pre-pandemic level, even before Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, one might have expected the Castillo administration to urgently seek to a find alternative sources for the 500,000 tons of fertilizer normally imported to Peru from the two Eastern European neighbours each year.

But Castillo was dismissive of the fertilizer crisis. On one occasion, he insisted that only the ‘lazy’ would go hungry. On another, he mused that the Incas had gotten by perfectly well without modern petrochemical nutrients.

Meanwhile, the corruption scandals came so fast that most Peruvians simply gave up trying to keep track. Castillo’s nephews, sister-in-law and presidential secretary were among the many from his inner circle who ended up in pretrial detention.

That presidential secretary, Bruno Pacheco, was caught with $20,000 hidden in his office toilet, next to Castillo’s own office in the presidential palace. His evolving explanations ranged from claiming the cash was to pay his lawyer to insisting that he was simply keeping his life savings in a safe place, despite his previous employment as a poorly-paid high school teacher and taxi driver.

Adding insult to injury, Castillo frequently came out with bizarre verbal gaffes, including during his occasional forays onto the international stage, to the intense embarrassment of many Peruvians. Once, while attending Chile’s presidential transition in March, he declared that he was enjoying his meeting with his ‘brother Santiago’ apparently confusing the name of the capital with that of his incoming counterpart, Gabriel Boric.

Predictably, his approval plummeted to below 20 per cent at one point, although it had recovered slightly, to around 30 per cent when he was impeached. Few Peruvians will lament his demise, although many will for years to come regret the lasting damage he did to public institutions and the economy.

Comments