On page 532 of my preview copy of this biography of Philip Roth there is a footnote. In it, Blake Bailey quotes from Roth’s novel Deception, where the character of Philip Roth asks his mistress what she would do if she was approached after his death by a biographer. Would she talk to him? She replies she might, if he was intelligent and serious. Bailey then adds, with self-deprecating wit: ‘Emma Smallwood did not respond to my request for an interview.’ Emma Smallwood is the name of one of Roth’s many lovers. It is not her real name.

OK, so: a fictionalised version of the subject of the biography I’m reviewing is quoted in words written by the subject of that biography, speaking about an imaginary biography to a fictionalised version of an unnamed woman. Her identity is then revealed, although with a fictional name, by the actual biographer, but only in her absence, in her refusal to say anything about the subject; which plays out — or doesn’t — the scenario the fictionalised Philip Roth was imagining when ‘he’ asked ‘her’ the question in the first place. It’s possibly the most meta footnote in the history of footnotes.

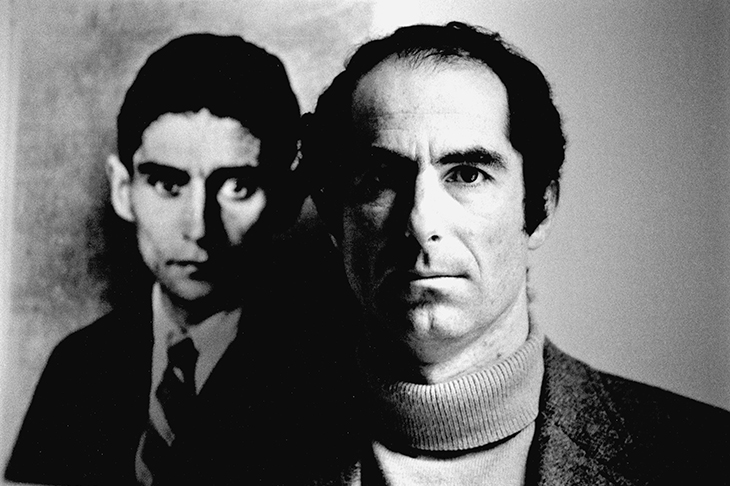

But then Roth was always the most meta of novelists. Philip Roth features as a character in six of his books, two of which (The Facts and Patrimony) are themselves biography. In nine other novels, the Philip Roth character is called Nathan Zuckerman. In four he is called Kepesh. In one (Operation Shylock) there are two Philip Roths. Many novelists debut with a roman-à-clef, and then leave their real life behind; but Roth’s whole oeuvre is a series of romans- à-clef. As he himself says in The Facts, his fiction is a process of ‘undermining experience, embellishing experience [and] rearranging and enlarging experience intoa species of mythology’.

Roth’s interest was not in the moral life, but just in life, lived, and then examined microscopically

Which might pose a problem for a biographer. Surely if you want to know who Philip Roth was, and how he lived his life and loves, it’s all there already, in the books, exhaustively (as Roth was often criticised for) mined? Well, that hasn’t bothered Bailey, whose double doorstopper of a book about Roth mines it again and again, in even greater detail than the man himself did over the course of that life’s work. In fact what Bailey is able to do, as a result of Roth’s insistent roman-à clefness, is continually trace the reality through the fiction. (Let’s call what Bailey is writing reality, despite Roth saying, elsewhere, correctly: ‘We are all writing fictitious versions of our lives all the time, contradictory but mutually entangling stories that, however subtly or grossly falsified, constitute our hold on reality and are the nearest thing we have to the truth.’)

Particularly, we learn who Roth the novelist is talking about other than himself — not just the avatars we all already knew, for example that E.O. Lonoff in the Zuckerman novels is Saul Bellow — but juicer info, such as the news that ‘the insatiable Drenka’ in Roth’s masterpiece Sabbath’s Theatre, is based on a neighbour who lived with her family near Roth’s country house in Connecticut and was originally his physical therapist. Oh, and who was Roth’s mistress throughout his marriage to Claire Bloom.

There are a lot of women who come and go in Roth’s life, talking not of Michelangelo but of Philip Roth and his various emotional and sexual issues. And herein lies the nub of the issue for Roth, and indeed all the men — Updike, Bellow, Mailer — who bestrode literary America in the latter half of the last century: they are being reassessed in the light of what I recently in a play called ‘the great correction’, and they are, as privileged, white men, targets (Jews, of course, don’t count).

Roth, as Bailey details, was always a target, initially in his career for the (absurd) charge of anti-Semitism — because he wrote Jews as real people, who told filthy jokes and masturbated and did various other lowly human things, as opposed to the somewhat hallowed, folksy way that Bernard Malamud and Leon Uris had chosen to depict them in the fragility of immediate post-Holocaust times. Roth’s comic honesty is important, now, at a time of great danger to the idea that literature should describe the world as it is, not as we would like it to be. As Zadie Smith is recorded by Bailey as saying:

I know that I stole Portnoy’s liberties long ago… He is part of the reason, when I write, that I do not try and create positive black role models for my black readers, and more generally have no interest in conjuring ideal humans for my readers to emulate.

The charge of how Roth treated, and depicted, women, however, is more threatening to his legacy, not least because he is a Jew, and not a woman, but more because maleness, along with whiteness, is where the cultural spotlight is presently being thrust away from.For me, the moment when the political tide turned against these ‘Great Male Narcissists’ as David Foster Wallace called them, was in 1997, when Wallace reviewed John Updike’s Towards the End of Time in the New York Observer, and said, of the main character in that book — but it could’ve been said of Updike himself, or Bellow, and certainly Roth: ‘He persists in the bizarre adolescent idea that getting to have sex with whomever one wants whenever one wants is a cure for ontological despair.’

It is true that a licence was granted between the end of the 1950s and the mid-1990s for male novelists to write excessively, and prize-winningly, about their libido, and that licence has now been revoked (not least, as it happens, for Wallace, whose legacy has recently been, for various types of uncovered misogyny, cancelled). Roth, who survived longest, dying in 2018, was the most aware of this, and most concerned about it, threatening to sue a prospective biographer, Ira Nadel (this biography, in its embrace of meta-ness, charts various attempts by other biographers to write this book before Bailey was anointed by Roth to do it properly). Because Nadel used as a reference point for Roth’s ‘anxieties about being emotionally engulfed by a woman’ Claire Bloom’s highly negative (and highly questioned, as fact, by Roth and indeed, Bailey) memoir of their marriage, Leaving a Doll’s House.

In a gentle, detailed, way, Bailey’s biography sides with Roth in most of his many travails. This is not the Albert Goldman version. Bailey says, in the conclusion, that his greatest debt is to Roth, ‘a person toward whom it was hard not to feel tenderly’. Even if that may not be something that would be said about him by either of his wives, I agree with Bailey when he adds: ‘He was all but incapable of dissembling his human essence.’ There is a stark, intense honesty to Roth. All this excavation of self over many books can only be done by someone prepared to stare the soul very resolutely in the face — and, unfashionable though it might be now, that makes me forgive him most things. These American post-war behemoths wrote unjudgmentally. They were not, like so many novelists now are, trying to teach the reader, and Roth is the most un-didactic of all. His interest was not in the moral life, but just in life, lived, and then examined microscopically.

He is also properly funny, and of course again unfashionably, for me funny forgives all. He wasn’t quite as great a prose stylist as Updike nor as garlanded as Bellow, but he was much funnier than either — the only high literary writer apart from Dickens who has ever properly made me laugh, the way proper comedy, Larry David or Chris Rock or Eric Morecambe, makes me laugh. I already knew this from the books; it’s there again in his life and correspondence. There are too many examples to list, but I laughed out loud at him saying, after Kafka’s niece,Vera Saudkova, turned down his proposal of marriage for a host of very serious sounding reasons connected to the volatile political situation in Prague at the time: ‘Or else she was just waiting for an offer from John Updike.’ I laughed even louder when, on hearing that his long coveted (and never awarded) Nobel Prize for Literature had gone in 2018 to Bob Dylan, Roth said: ‘It’s OK, but next year I hope Peter, Paul and Mary get it.’

And I forgive him sentence by sentence. Because that’s where the genius of these writers truly is, however much their gaze is snagged by their maleness. The bits in this book that made me stop and hold my breath and re-read were not the sexual revelations, of which there are many, or the gossip-bitchiness, of which there is more (we discover that in private Roth considered Salman Rushdie ‘a great writer’ and, as a human being, ‘an interesting shit’ ), or even the telling insights into his vulnerability that even Roth never used in his work, like the fact that he bought smart new shoes for a date with Jackie Kennedy but then walked all over Manhattan in them first so that it wouldn’t look like he bought new shoes just for the occasion — but simply, still, even though I’ve read them before, quotations from the books. When Bailey quotes Micky Sabbath opening a carton containing a few small trinkets memorialising his recently killed brother’s life and the author charts Sabbath’s suffering as ‘the passionate, the violent stuff, the worst, invented to torment one species alone, the remembering animal, the animal with the long memory’ it comes home to me how much Philip Roth, for all his flaws, for all that I know his legacy will continue to be judged in judgmental times and found wanting, deserves this riveting, serious and deeply intelligent biography: ‘Emma Smallwood’ was mistaken not to speak to Blake Bailey.

Comments