According to the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860), people prefer reading books about great thinkers rather than by the thinkers themselves because ‘like is attracted to like and the shallow, tasteless gossip of a contemporary pinhead is more agreeable and convenient to them than the thoughts of great minds’. Thankfully, this contemptuous attitude towards biographers has not deterred David Bather Woods, a professor at Warwick University, from taking a fresh look at one of the most influential yet misunderstood figures in western philosophy.

Woods’s prose is clear and compelling, though the book’s thematic structure is confusing. He argues that the defining event in Schopenhauer’s life was the suspected suicide of his father, Heinrich Floris. A wealthy shipping merchant from Danzig (now Gdansk, in Poland), Heinrich expected his only son to take over the family business, and coerced him into an apprenticeship as soon as he was old enough. But in 1805, when Schopenhauer was 17, he was found dead in a canal behind the family’s Hamburg home.

The official story was that he fell from an attic window, but privately his family believed it was suicide. For Schopenhauer, the consequences were mixed. Paternal objection to an intellectual career had been removed, and a large inheritance meant that he never had to earn a living. But he also inherited his father’s depressive temperament and was permanently affected by his death (as was his sister, Adele). The other contributing factor to his pessimism – and surely also his misogyny – was his troubled relationship with his mother, Johanna. One would have liked to see Woods drill deeper into that than he does.

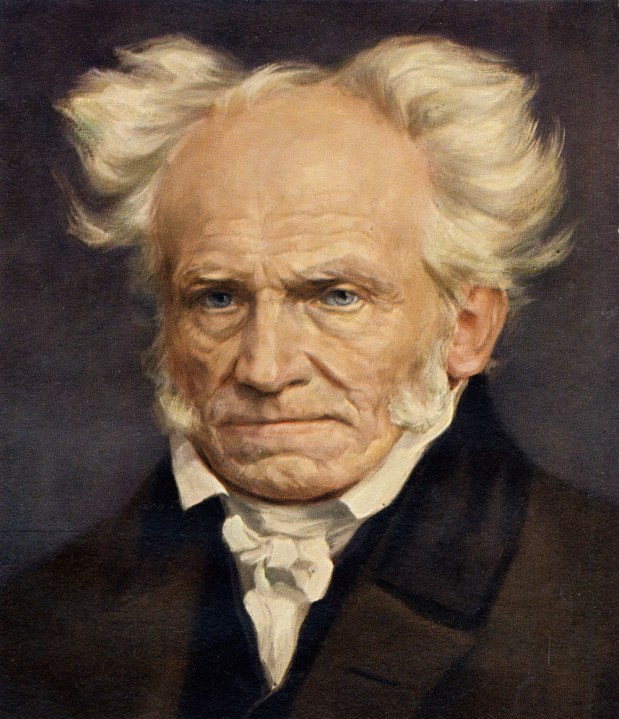

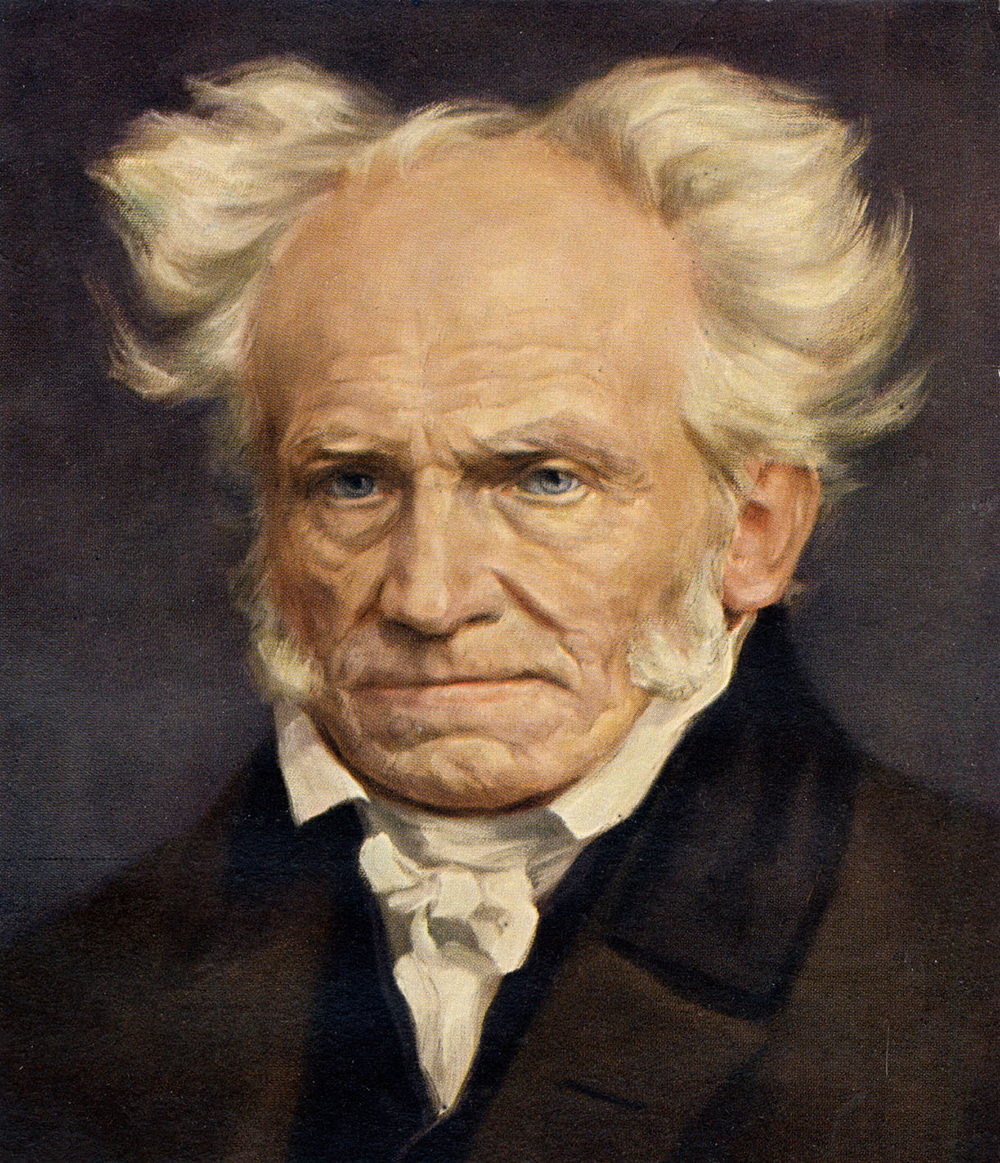

Schopenhauer was a difficult, arrogant man – a misanthrope liable to frightening explosions of temper. But Woods shows us the other side of his character, too. He loved dogs and was a passionate advocate of what we would now call animal rights. An accomplished linguist and Anglophile, he read the Times every day. There are touching scenes from the last years of Schopenhauer’s life, during which a young girl who lived beneath his Frankfurt lodgings befriended him and his beloved poodle, Atma. Lucia, as his neighbours’ daughter was called, would play with Atma in Schopenhauer’s study while he worked. He never married, but for more than a decade was involved with a dancer in Berlin named Ida, who he claimed was the only woman to become emotionally attached to him. Both of his daughters – mothers unknown – died in infancy. Perhaps most surprisingly, he was vain, and fussed terribly over the portraits and photographs that were made of him.

When it comes to philosophy, Woods follows most commentators in presenting Schopenhauer as a pessimist – which he was. But elevating this aspect of his thought above all others is problematic in a couple of respects.

First, it doesn’t capture how exhilarating, even life-affirming, Schopenhauer is as a writer. His commitment to thinking for oneself (the intellectual virtue he prized the most, expressed by a single German word, Selbstdenken), combined with his luminous prose, massive erudition and savage wit, make for a reading experience that is anything but miserable.

Second, an awareness of Schopenhauer’s pessimism is not necessary for an understanding of his formal philosophy. The foundational elements of his system – that is, his all-encompassing theories of reality and knowledge, developed in reaction to Kant – do not entail any existential value judgments, whether negative or positive. These are presented in his masterpiece, The World as Will and Representation, first published in 1818 when he was 30. By the time the third and final edition came out in 1859 he was 72, and the world was only just beginning to recognise its importance.

Together with a supplementary volume added to the second edition in 1844, The World as Will and Representation runs to around 1,000 pages. Frustratingly, Woods provides no account of the composition process, which was even more remarkable for occurring when Schopenhauer was in his twenties. He deals with its weighty contents in six pages. By contrast, entire chapters are devoted to Parerga and Paralipomena (from the Greek, meaning ‘offshoots and offcuts’), a volume of essays released in 1851 that finally launched Schopenhauer’s ascent to fame.

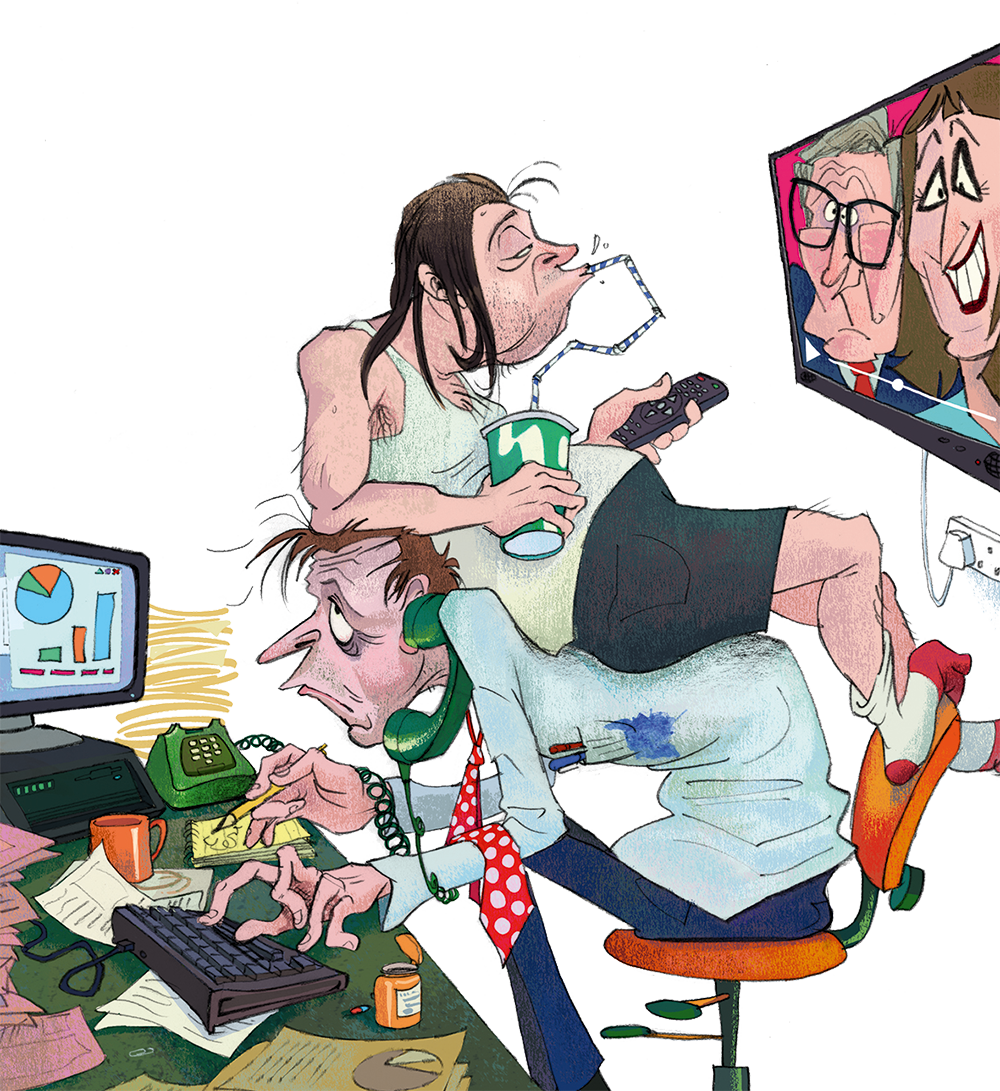

Parerga contains Schopenhauer’s musings on topics such as madness, suicide, education and religion, and displays his pessimism to a much greater extent than his philosophy. No good book about him could leave these essays out. But as indicated by the title Schopenhauer chose for this collection, they were intended as optional add-ons to his major work. Readers of Woods’s biography are at risk of forming the opposite impression – that Parerga was Schopenhauer’s defining achievement, whereas The World as Will and Representation was a youthful prelude.

Flaws and omissions aside, Woods has written an engaging book that is likely to succeed in a way that Schopenhauer would have valued – by turning readers on to the philosopher’s works themselves. There, they will discover a thinker who has much more to offer than just a gloomy view of life.

Comments