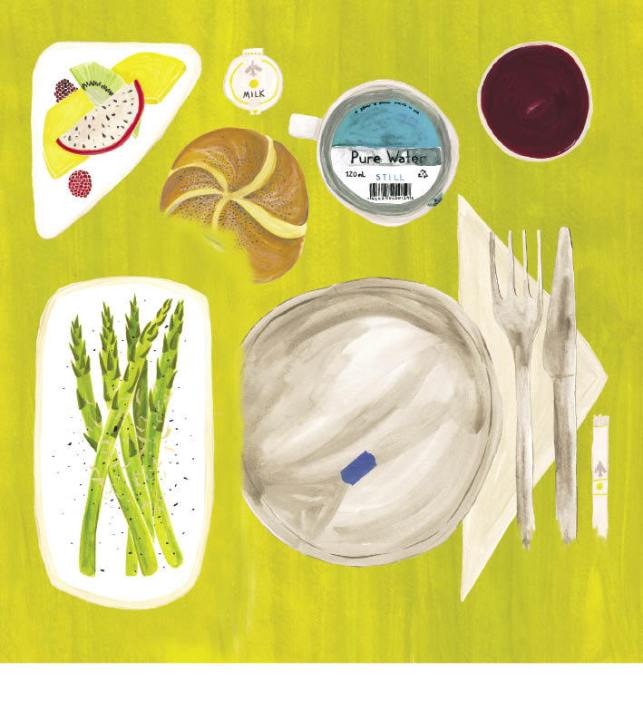

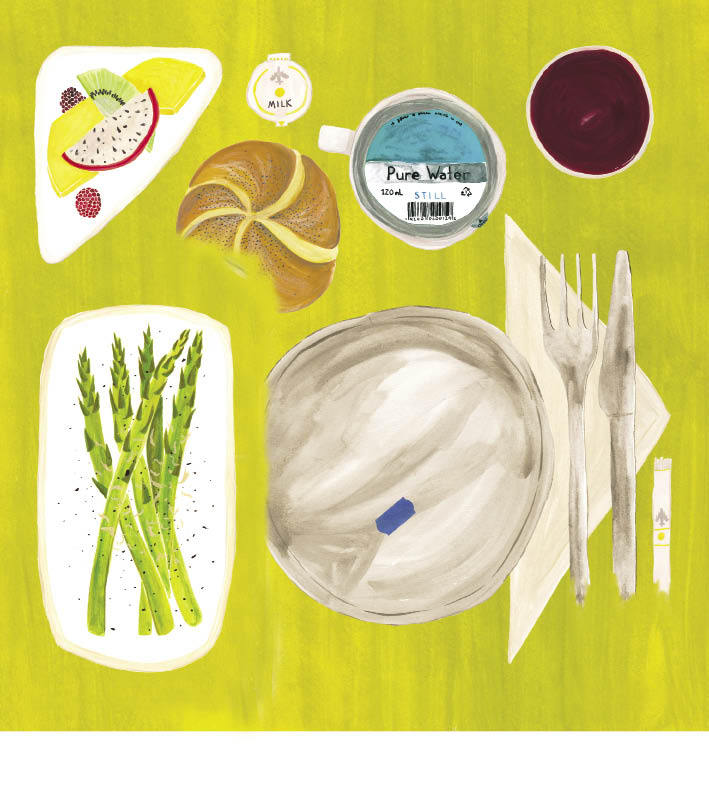

Airline food does not enjoy the best of reputations, but with a new breed of on-board cooking and menu selection systems now emerging, its future could be a journey back to basics – with boiled egg and soldiers. Dan Jellinek reports

Airline food has long had a poor reputation — odd-tasting, odd-sized and arriving at odd times. In recent years, however, innovations in preparation and ingredients have seen huge improvements, not only towards the front of planes, but in the cheap seats where most of us travel as well.

To understand the challenges faced by airlines in serving any halfway decent food at all to passengers, you have to grasp the logistics.

British Airways serves around 100,000 meals a day on its flights worldwide, all of which have to be at least partially pre-prepared and pre-packed, then loaded onto flights in the right combinations.

Up to 16,000 meals a day — all the catering for the airline’s outbound long-haul flights — are created at a single unit on the outskirts of Heathrow airport: a vast dedicated kitchen and warehouse facility manned by 980 staff and operated by Gate Gourmet, the UK’s largest independent airline caterer.

The food is created in several stages, the first of which involves the arrival into one bay of all the ingredients; as fresh as possible but much of it of necessity at some stage of pre-preparation, such as pre-chopped ginger or liquid eggs for scrambling.

Some is then cooked or part-cooked in industrial quantities: cages of vegetables, for example, are lowered into vats of boiling water on hoists, then into another of cold water to fix the blanch. Given the scale of the operation, it is impressive how much of each meal is freshly cooked.

‘I look at an economy meal and I think it’s a good meal for what it is,’ says Charles Abraham, commercial manager at Gate Gourmet. ‘For first class, of course, it’s even better: soup made fresh here every day, and a bakery where we freshly bake as much as possible such as scones and chicory tarts. Everything is used within 24 hours.’

For first class and Club World, many meals are created in kit form, for flight attendants to assemble: some bits may be reheated, others sprinkled, drizzled or nestled piece by piece. Most of each menu by flight class changes month by month, with the entire set of menus changing every quarter, and each year’s cycle also changing. Some British classics like roast beef or scones with cream and jam do run through, but the emphasis is now on seasonality, says BA’s development chef Steve Walpole.

Thus the spring menu featured sea bass from Anglesey, cockle and clam vinaigrette and broccoli — ‘absolutely as seasonal as it could be,’ says Walpole. Meltingly soft longhorn rump tail, braised for up to five hours, is also on offer.

‘In the past, airline catering was too simple — we played it safe. You would never see a piece of braised beef or a pie: it was always prawn cocktail. Then we went too far the other way, too complicated. Now we’re back to going for the best ingredients, keeping it simple.’

So how important is the food in a passenger’s choice of airline?

Singapore Airlines’ food and beverage manager, Hermann Freidanck, says it is never going to be the main reason why people choose a flight, but it is important. ‘In principle, every airline is a transportation company: our main job is to transport people from A to B. But we are all transporting people in a tube, and all the tubes are alike. The real difference is what experience we have, so food is very important.’

In the old days, aeroplane food was heavy, he says. ‘It was used to fill you up and make you sleepy. But now people watch cookery shows, they are much more sophisticated when it comes to food. So you have to take account of that, and raise the bar.’

Another expectation that has changed is for food to be available of many ethnic varieties, Freidanck says. ‘An international airline that doesn’t offer Japanese, Indian, Chinese, Thai food — I don’t think you could do that in today’s world. So you need the ingredients, the skills for all these.’

And it’s not just the food that needs to change, the whole structure of the Western meal — starter, main, salad and dessert — is not suited to many food cultures, with many Indian passengers, for example, preferring to eat a thali, with different types of dish served together around a plate of rice. This means changes in everything down to the tray you serve the food on, says Freidanck. ‘Now if you fly to Beijing, you have a Chinese tray where all parts are different, even in economy.’

Freidanck accepts that ‘real cooking’ is not possible on board a plane — ‘a flambée would not work very well on board’ — but says good results are made possible by observing certain rules.

‘Like with fish, you must not use too fine a fish, because when it heats, it dries out. So you choose more solid fish, with more fat. Bread dries up three times as fast, so you can use different recipes. And when you heat vegetables it lets out steam which can dilute a sauce and make it tasteless. So we always have separate sauce.’

The air conditioning on planes also dries out people’s mouths, diminishing most taste sensations, so you have to account for that by adding a bit more spice — ‘make it more hearty’, says Freidanck. ‘There are many things you can work on: airline food doesn’t have to be bad. People like to have a good salad these days, maybe with a smoked chicken breast, instead of sitting there for hours, waiting for three courses. Or a piece of cheese and a glass of red wine. Or maybe a burger — but a good burger.’

So what does the future hold for airline food?

One key development in long-haul flights will be the introduction of new kitchen technologies in some of the new breed of ‘super jumbos’ like the Airbus A380 and the Boeing 777. At the beginning of this year Air New Zealand began a three-year switchover to the use of 777s for all its long-haul flights, and as part of the process has reviewed every aspect of its food from quality to style, variety and cooking method.

‘With airline food, variety is the key, and we looked at how to break the cycle of only two choices in economy,’ says Matthew Cooper, head of long-haul customer service at Air New Zealand. ‘We knew two options was not enough, to just offer chicken or beef casserole. We wanted to add deli salads, crunchy lettuce — things you don’t normally associate with airline food.’

As well as main meal times, the airline has an on-demand ordering service via the new breed of digital in-flight entertainment system, recognising that people on very long-haul flights indeed — from London to Auckland — will get hungry at different times and may be looking for a snack.

‘People are a lot more likely to order food on-screen than by using a call bell,’ says Cooper. There are other advantages to choice such as the ability to order decaf coffee, to look at menus and images of food before ordering and to order snacks at any time, on demand. All passengers will also be able to read through a detailed wine guide, previously only available in business class; and there may be the chance for economy passengers to order anything available in the higher classes, for a surcharge.

Switching to the new larger planes will also mean larger, better galleys that are more like normal kitchens, and later this year for Air NZ, the use of induction ovens — a new technology which allows not just reheating but frying on a hot plate, allowing steaks to be cooked fresh, for example, or a breakfast of fried, poached or boiled eggs and fried tomatoes. There will even be the option of real toast, as one of only a few airlines to have toasters on board.

‘We asked people what they would like if they could have anything, and their answers were simple — things like boiled egg and soldiers. But they said if you do it, you have got to do it right.’

Boiled egg and soldiers at 40,000 feet: a superb use of the latest aeronautical high-tech wizardry. The future’s bright — the future’s porridge.

Comments