The 20th century was an amazing time for Russian pianists, and the worse things got, politically and militarily, the more great pianists thrived, despite the extreme danger and discomfort in which they lived and in which some of them died. If we think immediately of Richter, the greatest of them all, and Gilels, there are at least 20 more that we could add without exaggeration. One of the most important was without question Maria Yudina, born in 1899, who astonishingly survived until 1970.

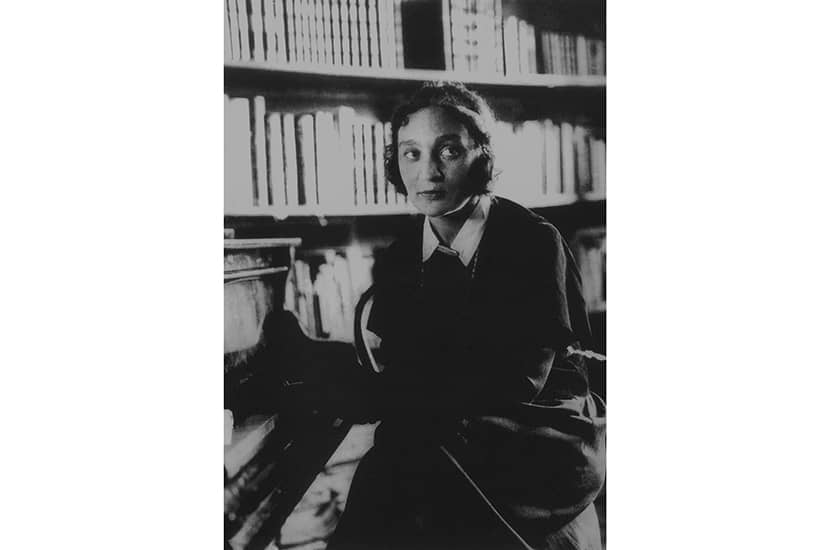

She was not just a sovereign artist but an eccentric of the kind and degree that only Russia seems able and willing to supply. Reading a biography of her as thorough and informed as Playing with Fire, one grows ever more incredulous that she survived so long and went on performing until very near the end of her life.

The author is extremely well placed to narrate Yudina’s life and provide some insight into her art. Elizabeth Wilson lived in Russia for years, was a pupil of Rostropovich and familiar with all the major Russian artists of the latter part of the 20th century. Though she never heard Yudina in the flesh, there is a large number of records and tapes of her playing, most of them ‘live’. When you read of the conditions under which they were made, their sound quality, though far from ideal, is good enough to create a vivid impression of what a performance by Yudina was like.

She was indifferent to pain and would practise until the whole keyboard was stained with blood from her fingertips

Wilson doesn’t give an estimate of how many performances Yudina gave, but it must have been thousands, sometimes more than one a day, and her programmes tended to be huge: three concertos straight off was nothing unusual. Her musical gods were Bach, Beethoven and Schubert, performances of all of them available on record. But she was endlessly curious, and had an appetite for contemporary music which often brought her into conflict with the authorities.

She was especially devoted to Stravinsky’s music, which was officially disapproved of, indeed banned until the composer’s visit to his native land in 1962, after 46 years (wonderfully recounted by Robert Craft in several books). However, Yudina expected Stravinsky to be an intellectual, which he wasn’t at all, so they couldn’t discuss what she most wanted to.

No one could say she wasn’t an intellectual, though of a peculiar kind — a Russian kind, one is bound to say. She was Jewish, but converted early to Roman Catholicism, and remained in the fold throughout her life. That didn’t prevent her from exploring alternative versions of the faith, and she read encyclopedically, endlessly searching for different interpretations and joining one dissident group after another with all the acrimony that theological matters engender. What she called her ‘secular’ reading, of which she somehow managed to do a great deal, was odd: The Three Musketeers was her favourite novel, and she hated Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus.

Often her changes of outlook went with fresh loves — in the course of her life she had almost as many near-affairs as religious commitments. What makes her so rare is that she actually put Christ’s commandments into practice. Though she earned decent amounts for her concerts, she invariably gave it all away to anyone who looked needy. She had endlessly to borrow for the basic things in life, spent much of her time in frozen rooms practising on a borrowed piano (she never owned one) and wore comically absurd clothes: always a vast black amorphous gown and gym shoes.

She would practise until the whole keyboard was stained with blood from her fingertips, and not stop even then if she didn’t feel like it. Her indifference to physical discomfort and pain was total. So was her outspokenness, so that the point comes when one wonders how, given the number of her friends and enemies that were disappeared, she managed to survive. True, she was Stalin’s favourite pianist, but that didn’t necessarily guarantee her safety, considering the ubiquity of intrigue among the Soviet leaders.

In a way, Yudina is incomprehensible, since her outlook on the world, what-ever vagaries it suffered, had a central solid core alien to any that we have now. She believed passionately in the power of Art (all the arts). She was a contemporary of Bakhtin, one of the foremost of all the Russian theoreticians of the time, and though they naturally disagreed, the atmosphere in which they argued was one which allowed for extravagances which it may be hard for us to take seriously. If Christianity is true, as for Yudina it was, and Art is religious, and it is, then playing great music is an act of prayer. So much of her life was spent in devotion, even if the strings were untuned and she had to take off one of the piano’s legs and burn it to keep from freezing.

It’s not surprising that Bach was her favourite, and she left many recordings of his works, especially of ‘the 48’. There is no orthodoxy about how they should be played, and the variations among performers are enormous. Yudina plays them with something of Romantic intensity, fine by me. On the other hand, when she plays Beethoven’s Hammerklavier Sonata, she varies tempi to a degree that induces vertigo. The same goes for Schubert’s last Piano Sonata, and for many other things. You might hate it, but it makes you think afresh, and sometimes there is a revelation.

The best buy is on the Scribendum label, where the sound is less good than on some others, but it’s extremely cheap and. despite Wilson’s animadversion, that is what I would recommend to begin with: 26 CDs for about £26.

As for the book as a whole: it gets bogged down in names, of which there are sometimes as many as 20 on one page. Remembering Russian names is never easy, and I found Wilson too generous by at least a half. But you get the outline, the pattern, of an incredible life, and an account — this one too brief — of the meeting between two women who may be the greatest female artists of their nation in the century: Yudina and Marina Tsvetayeva. Yudina wanted someone to translate the words of some Schubert songs into singable Russian, and Tsvetayeva, supreme poet and author of the staggering essay ‘Art in the Light of Conscience’, was suggested by Pasternak. Yudina sought her out, found her in a state of terminal desperation, hurried away and then learned that Tsvetayeva had hanged herself. ‘But I should have thrown myself at her feet, kissed her hands and washed them with hot, bitter tears. I should have removed some burden or other to lighten her load.’

Comments