One of the promises from the last round of ‘new politics’ pledges when the Tories were in opposition was a cut in the number of special advisers in a government, on the grounds that SpAds are evil beasts who cost a lot of money. Like many ‘new politics’ pledges, though, this sounded superbly pious in opposition and turned out to be a real pain in the backside in government. It turns out that SpAds are actually really useful if you want to get things done as a minister, if you want to know what other ministers are trying to do to stop you getting things done, and if you want to have a hope of the public reading about you getting things done in the newspapers.

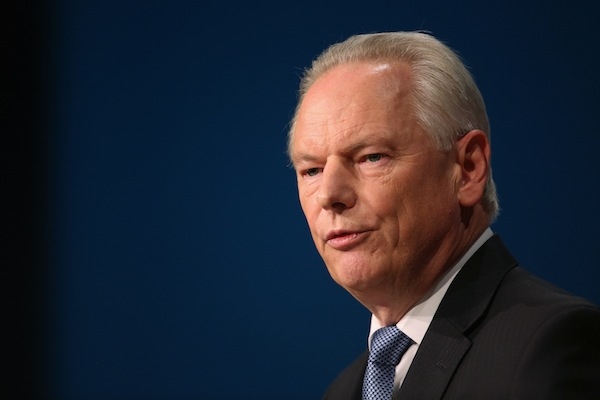

The number of SpAds has been steadily rising as more members of the government realise this, but today Francis Maude announced plans for Extended Ministerial Offices. These are souped-up private offices based on operations in other countries (it’s worth reading IPPR’s report on this, while Maude and colleagues have drawn extensively from) and would contain additional special advisers, civil servants and external appointees with a specific expertise lacking in that department.

Maude told journalists this morning that certain departments were already ‘giving thought to it’, and that the new offices wouldn’t represent a ‘massive expansion’ in numbers. He suggested that the offices could contain around 20 members of staff. They will also benefit from a number of bells and whistles that will make it quite difficult for ministers to dismiss having an EMO, as a member of the Prime Minister’s implementation unit will join as soon as it is set up to help policy progress.

Now the biggest criticism from opponents of these reforms is that they represent a politicisation of the civil service and that they risk pitching ministers against the rest of their departments. But Maude and his colleagues argue that this is simply a means of helping ministers to be more effective by hiring people whose skills wouldn’t normally be found in the civil service. It also means that extended ministerial office staff can stick to a minister’s brief, rather than fearing that because the permanent secretary is their ultimate boss, their own career will be damaged by carrying out that minister’s instructions. Members of the office would be accountable to the minister, who would personally appoint them.

Finally, it is worth noting that one of the most effective Whitehall departments, Education, already has a similar arrangement in place. Ministers keen to enjoy the same success as Michael Gove has with his reforms will find these extended offices very appealing indeed. Many (particularly Lib Dem ministers) have learned the hard way that life as a minister without adequate support is very difficult indeed. These changes are an example of politicians being grown-up, rather than pious, about government.

Comments