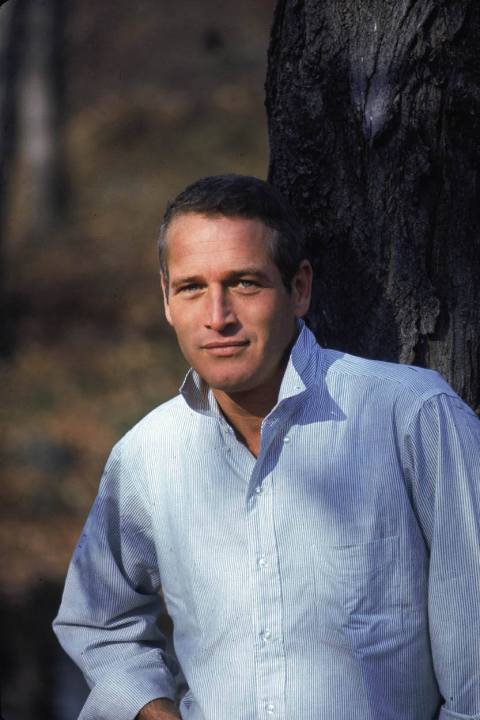

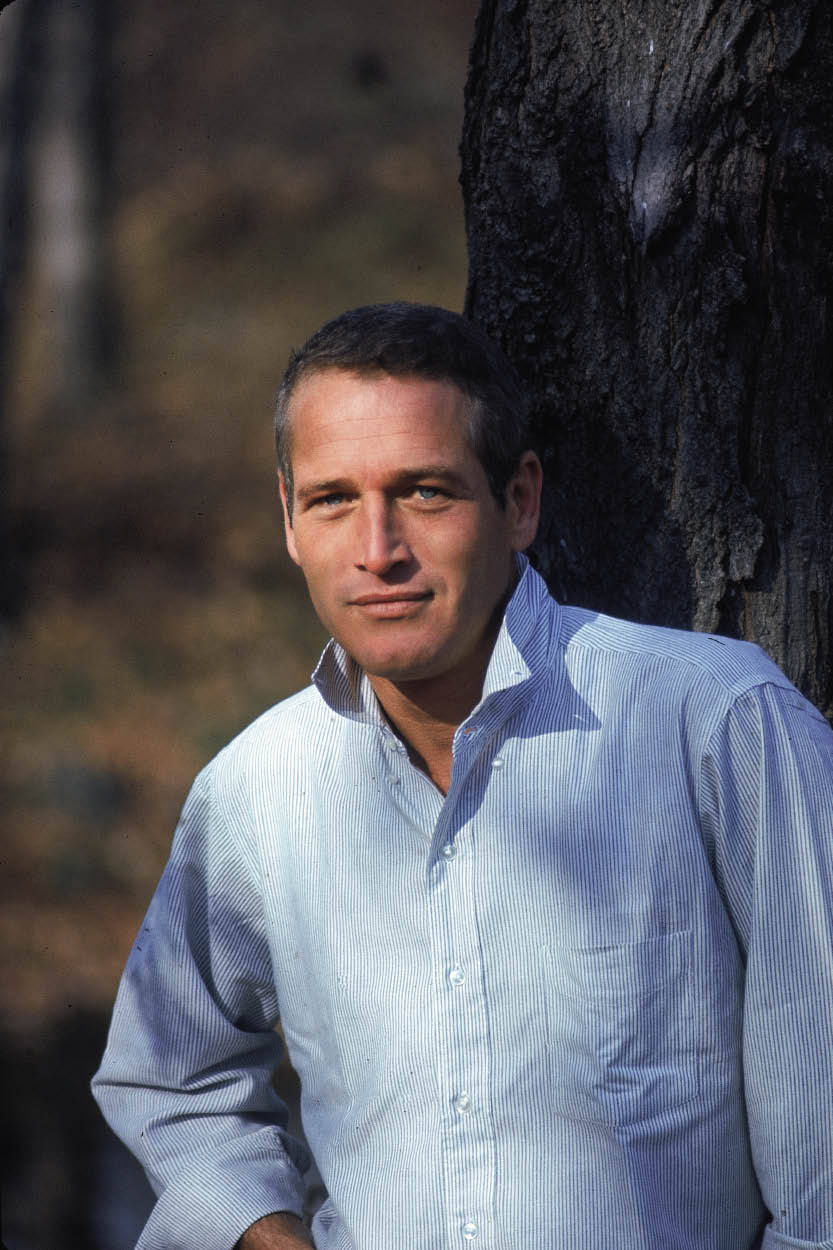

In his memoir Somebody Down Here Likes Me, Too, the boxer Rocky Graziano, on whom Paul Newman based his performance in Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956), describes the actor in perfect Runyonese:

I could see right off there ain’t one thing phony about this guy. Maybe there was. He was too good-looking. In fact, the guy is pretty… He’s got bright blue eyes, but when you look in ’em you see a hard look dancing around inside. Only one other guy I see these same eyes on an’ that was another friend of mine, Frank Sinatra. When their blue eyes spot a wise guy, the eyes say, ‘Don’t fuck with me, man!’

To judge by Paul Newman, a monumental cuttings job by someone who never met him, and Paul and Me, an anecdotal memoir by his oldest friend, Graziano got him about right. Despite his close friendship with Gore Vidal — they used to go on holiday together, and one can hear Gore drawl, ‘No need to be shy, Paul, you don’t need a swimsuit among friends’ — Newman seems to have been a pretty straight guy.

He may not have been a great success as a father, but that was more the world’s fault; his daughters preferred ‘doggy- looking guys’, and his son, who tried to follow in his footsteps, died young of an overdose.

He left his first wife and children for Joanne Woodward, of whom he gallantly said, ‘I have steak at home, so why go out for hamburger?’ And he cheated on her, too, with a Nancy Bacon, prompting the riposte that he had steak at home but went out for bacon. The marriage survived, though, and Newman’s unreconstructed gallantry with it. In 1997, when he was 72, Woodward visited him on the set of a turkey called Twilight, and he said to a fellow actor, ‘Will you look at the ass on her?’

In every other facet of a multi-faceted life — as a champion racing-car driver and owner, racing into his eighties, as an organic salad-dressing tycoon, as a supremely modest philanthropist, and above all as an actor and movie star — he was a decent chap or good bloke, sans reproche.

Nor is there much doubt of his prettiness. He was prettier than the young Marlon Brando, who was his contemporary at the Actors Studio, and his rival as a player of anti-heroes, particularly in dramas by Tennessee Williams. Brando won, because he was an anti-hero of the counter-culture, and presented a more authentic ‘sexual threat’ — or ‘eruptability’, as Newman put it.

‘Eruptability is always in the potential of the masses-type hero,’ he noted of Brando. ‘And the quality I carry is Ivy League — Shaker Heights and like that.’ (Shaker Heights is a suburb of Cleveland, where his father had a sporting goods store, ‘the best in Ohio’; he went to Kenyon and Yale.) Newman kept his looks, though, and was a pin-up to several generations. One of his daughters was shocked to read his fan mail: ‘I’ll tell you one thing I’ve learned. Women in America are absolutely not getting laid! These women are actively pursuing my father.’

He was a phenomenally lucky guy, and his belief in luck was the closest he came to religion: ‘For me, being lucky starts when you have a good sperm ride that makes a good womb connection that produces lucky genes.’ He inherited his entrepreneurial streak from his father, and at Kenyon ran a profitable laundry offering free beer — an inspired application of Gillette’s business model. In his seventies he acquired an interest in a Volvo/Mazda dealership in Connecticut.

On an early date with Woodward, a dressed salad was brought to their table. Newman took it to the men’s room, washed it, dried it with towels, ‘and returned to the table,’ she recalled, ‘to do things right, with oil cut by a dash of water’. Years later, with his friend A. E. Hotchner (who claims to have been so poor as a child that he had to ‘eat pictures of food that I cut out of magazines’), he took his dressing to market, following it with such products as Newman’s Own Industrial Strength All-Natural Venetian-Style Spaghetti Sauce. By the time he died in 2008, the business had factories in Scotland and Australia and a profit of $260 million a year, all of which, every Christmas, Newman and Hotchner gave away to charity.

Newman was hard to pin down as an actor — he could do neurotic low lifes as well as romantic leads — but as a man he was consistent, recalling that line in The Hustler, ‘It’s not enough to have talent. You’ve got to have character.’ He may be a bit dull to read about, but he was a hero.

Comments