‘Give me a child until he is seven and I’ll give you the man,’ said St Francis Xavier, co-founder of the Jesuit order. Public schools are given children until they’re 18 — it’s no surprise they can control their world view for the rest of their life.

And their language, too. When Prince William teased his new-born son for his ‘tardiness’ in arriving some time after his due date, he was unconsciously unearthing the memory of Eton’s ‘Tardy Book’ for boys who were late to lessons — erm, I mean divs.

Twenty-five years after leaving Westminster School, I still think of its main hall as ‘Up School’, of afternoon sport there as ‘station’, even of my own clothes — rather than school uniform — as ‘shag’. Yes, really.

That’s the funny thing about school slang. Hypersensitive teenagers, terrified of saying something silly, let alone something sexual, are set free by the conventions of slang to speak a nonsense language without fear of embarrassment.

You’re safe from ridicule because you’re sanctioned by the universal use of slang by everyone around you. Public schools — particularly boarding schools, particularly remote, rural boarding schools — are like undiscovered islands in the far reaches of the Pacific. The tiny group of indigenous pygmies speak and develop their own language, untouched by the outside world. Identical words have different meanings on different islands. In ancient Winchester slang — or ‘notions’, as slang is called there — a ‘bob’ is a big, white beer-jug. At Eton, a ‘wet bob’ rows; a ‘dry bob’ plays cricket; and ‘slack bobs’ do neither.

In these exotic bubbles, archaisms linger on for ever. The Lower and Upper Shell — junior years at Westminster — derive from the semicircular apse at the end of Up School, where the boys were taught several centuries ago.

Given that public schools were largely devoted to classics for half a millennium, a lot of archaisms are -Latin-based. The popular term for a short holiday, an ‘exeat’, is formed from the tricky subjunctive of exit, meaning ‘Let him go away’. Eton’s ‘dames’ — their matrons — get their name from the Latin domina, meaning mistress. Wykehamists came up with the term nihil-ad-rem — literally ‘nothing to the thing’ — to mean vague.

The formality of Latin was often abbreviated by boys. ‘Aegrotat’ — the Latin for ‘he is ill’ — was used for the result granted to an invalid who was too sick take his exams. Abbreviated to ‘Aeger’, it became popular at Felsted School, Essex, as recorded in an 1890 edition of the Felstedian: ‘What’s up with Smith? He went aeger before school this afternoon.’

The -er suffix is particularly widespread. ‘Brekker’ — in wide use at Stonyhurst and Harrow in the late 19th century — became universal in the 20th. The -er habit migrated to universities: in a self-mocking way, the -Martyrs’ Memorial on St Giles in Oxford was nicknamed the ‘Maggers’ Memoggers’; in 1883, yellow Canadian canoes on the River Cherwell were called ‘Cannager-canoodles’.

For all its archaisms, school slang still changes with time. I never called milk ‘bag’ at school — although, according to the Public School Word-Book of 1900, it was popular at Westminster a century ago. Nor did I have to ask masters for a ‘dor’ — an ancient Westminster term for permission to have a doze (short for dormio — I sleep, in Latin).

And Westminster’s Birch Room — once extremely popular with masters — is obsolete these days; as is the Block in Eton’s Upper School library, where a boy knelt to be flogged. ‘Boner’, old public school slang for a sharp blow on the spine, now means something entirely -different. I imagine the Bearded Cad no longer exists at Winchester. That was the nickname for the college porter who carried luggage from the railway station. The Public School Word-Book says that he was named after ‘an extremely hirsute individual who, at one time, acted in the capacity’. Do pupils at Christ’s Hospital still call the first Monday after the end of the holidays ‘Funking Monday’ — surely too much room for improvisation?

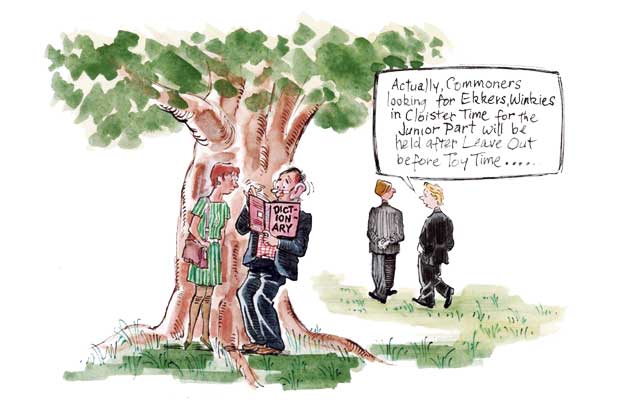

Traditionalists needn’t worry, though. There’s still some tremendous Molesworth language around. New bugs at Winchester can still buy Winchester Notions, which lists the school’s slang. Invaluable if you want to translate something like ‘First-year boys, not in college but keen on exercise, will take part in the cross-house matches after half-term, before evening prep, under the supervision of all masters, the governing body, and the two joint heads of school.’ In Winchester slang, that reads, ‘For Commoners looking for Ekker, Winkies in Cloister Time for the Junior Part will be held after Leave Out, before Toytime, in the presence of all Dons, the Go. Bo., the Aul. Prae and the Sen. Co. Prae.’

Clear as mud — or, as a Wykehamist might say, it’s all pretty nihil-ad-rem.

From the Spectator’s Independent Schools supplement September 2013

Comments