Here at last is a novel informed by exceptional intelligence. The blurb states that the author, Simon Mawer, was born in England, but it seems likely that his ancestry was Czech, since he is acquainted with the language and the customs of pre-war Czechoslovakia and has learned of its travails during the German and Russian occupations. And it is clear from his narrative that the country was both sophisticated and cultivated in its manifestations, influenced perhaps by its position at the heart of Europe and subject to both the best and the worst of its fashions. This alone would mark it as unusual: the clarity with which it is written is almost unfamiliar and certainly to be admired.

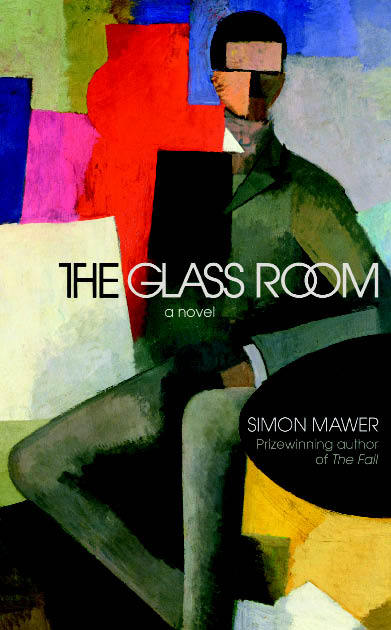

The Glass Room of the title is part of a futuristic house designed by a German architect, Rainer von Abt (this is not quite a fiction, since a prototype certainly exists). This house has been commissioned by Viktor and Liesel Landauer, and its most remarkable feature is the lower ground floor which consists almost entirely of broad windows looking out over the garden. Living quarters are on an upper floor. The furniture of the Glass Room consists of chrome pillars, an onyx screen, a piano and little else. Chairs can be moved in for gatherings and music recitals, of which there are many.

The household consists of Viktor and Liesel and their children. In time they are joined by Katalin, Viktor’s mistress, and her daughter Marika. This addition is necessitated by the German invasion and the beginnings of an era of displacement from which there is no real recovery. The Landauers are wealthy, while Katalin, who acts as nanny to the children, is entirely dependent. The combination works well enough. Liesel is obliged to make a friend of Katalin, although she has more in common with her social equal, Hana. The two women are cleverly characterised. Hana is prodigal with her affections and entirely amoral, while the prudish Liesel is almost attracted but remains essentially a sharp-tongued bourgeoise who entertains aberrant fancies.

During the German occupation the house is turned into an anthropometric centre testing for racial stereotypes, and of course, racial purity. Ironically the Glass Room is the perfect setting for this type of investigation. Its owners are almost safe in Switzerland and wealthy enough to make their way to America, although Katalin, who has only a Nansen passport, is detained. The Russians, when they arrive, turn the house into a rehabilitation centre for disabled children. The former owners dematerialise: the house endures. Historical events are merely the vicissitudes which the house is obliged to undergo as evidence that its inhabitants, past and present, are temporary occupants, nothing more. The house remains, its structure inviolable.

All the characters reappear, in one form or another. Lanik, the Landauers’ former caretaker, becomes a party functionary. Hana too has some sort of official standing as part of a Heritage committee and is briefly valuable to the authorities as historian of the house. Her husband, a Jew like Viktor Landauer, has died in Auschwitz. It is true that in the latter part of the novel the interest tails off, but, like the house, the structure endures. The ending is infinitely moving. The country is on the verge of restoration, of normalisation. Architecture and history come together again. There is a resolution when Liesel, now old and blind, returns after long exile to reclaim her house. Even the repossession seems insignificant; it is always the house that seems emblematic.

It should be emphasised that this is not the sort of house that features in most English novels. There are no echoes of Brideshead here. This house — long, low, rectilinear — does not inspire sentimentality. It is its unfamiliar purity which is its outstanding feature, and this purity also characterises the novel itself. There is little sex, little weather, and a total absence of stylistic flourishes. It is, in sum, a humanist novel, unusual in its breadth and scope, and also in its dignity. Definitely Bookerish.

Anita Brookner’s latest novel, Strangers, will be reviewed next week.

Comments