Halfway through Lady Fanshawe’s Receipt Book Lucy Moore takes a moment to regret the vast tracts of the past that are lost to us. How lucky we would be if more examples of our ancestors’ daily interactions with others, what she calls ‘the scraps of daily life we take for granted’, had been preserved.

Instead, of course, we must make do with the flotsam that has survived, and to try to coax quotidian objects into offering up glimpses into lives that might otherwise have remained obscure. Court records, depositions and wills have all been interrogated by historians, as have more unlikely items, such as the collections of culinary and medical preparations compiled by women from ‘receipts’ given to them by their friends and relations.

Moore has used the receipt book owned by a Stuart loyalist, Ann Fanshawe, along with her memoirs, to produce a lively, affecting account of one family’s fortunes in a world turned upside down. In the process, she tells a broader story of how ordinary people experienced the English civil war, an earthquake in our nation’s history.

The daughter of a prosperous servant of the king, Ann married, at 19, Richard Fanshawe, a man 17 years her senior, who combined his career as a courtier and diplomat with a taste for literature. It was a love match that would endure until his untimely death, but Richard’s position at Charles I’s court, and the loyalty he would continue to show to his son, Charles II, meant that their fate was hitched to the Royalist wagon.

In the years after Charles I’s execution the Fanshawe family would manouevre around Britain and Europe, pushed about by the new king’s quixotic attempts to maintain the fiction that he was a sovereign in anything more than name. Those Royalists who stayed close to their homes and families saw their goods seized, and were often subjected to heavy fines. More honour accrued to those who stayed alongside Charles II, but it was a court riven by plots and factions, and most were condemned to a poverty-ridden existence that often thrust families apart.

Ann, like many other Royalist women, played a crucial role during these threadbare years of exile and separation — seeking preferment and passage for her husband, visiting him in prison, nursing him when he fell sick and raising the money needed to fill the gap left by the loss of their income and estates.

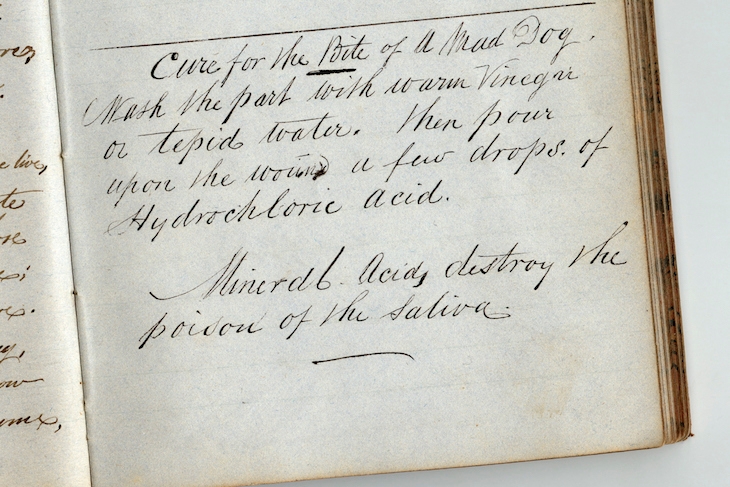

Royalist women were engines of continuity and connection, helping to preserve both the fabric of a world that they feared was disappearing, and the networks that were themselves a way of guaranteeing the survival of the rules, codes and habits that would be a foundation of the new society that they hoped their resilience would eventually usher in. Receipt books such as Ann’s were emblematic of this process: texts designed to salve suffering Royalist bodies as well as the ailing body politic.

With all this heavy lifting to do, it is perhaps little surprise that the remedies they contained were ascribed protean qualities that make the present claims about superfoods seem modest:

The water calld Aqua Mirabilis disolueth the imposthumation of ye Lungs… it openeth Melancholy, it expelleth ye stopping of ye Urine, profiteth ye Stomach very much, it also conserved Youth and preserueth the Memory.

And, of course, life, always precarious in early modern Europe, was even more so during the civil war and its aftermath. Including miscarriages, Ann had 20 babies, but only five reached adulthood. She may have been compassionate and resourceful, but she was helpless to save them, and the pain she suffered pulses through this book. In a letter to her husband, she ruefully acknowledges the extent to which their fate lay out of their hands: ‘Alasse, how can you talke of deffying fortune, noe body lives without it.’

The Fanshawes were never quite able to harness their own destiny. The rewards they believed their patience and loyalty deserved failed to materialise after the Restoration — but if Ann could not defy fortune, then at least the survival of her own writing, and Moore’s subsequent reconstruction of her biography, has ensured that she has been able to dodge the oblivion to which so many of her contemporaries have been consigned.

Comments