On a table in Robert Jenrick’s parliamentary office lies the first part of Ronald Hutton’s biography of Oliver Cromwell, a conventional MP who became radicalised by events and usurped a monarch. The shadow justice secretary is very on message when it comes to the prospect of regicide in the Conservative party (‘I’m just doing my job. Kemi is the leader’). But as one who recently travelled to Calais to berate the French authorities for facilitating Channel small boat crossings, Jenrick has found unlikely inspiration in another bloody-minded leader. ‘I’ve been reading biographies of de Gaulle over the summer and he had a line that “Treaties are like roses, they last as long as they last”. I think that’s where we are.’

In his sights are Britain’s membership of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the Refugee Convention, which he believes are stopping the UK from deporting migrants who arrive illegally. Kemi Badenoch is due to set out Tory policy at the party conference in four weeks’ time. But in a pointed intervention designed to shape the debate, Jenrick makes it clear that his party must go much further and emulate Nigel Farage’s stated aim of mass deportations.

Jenrick says ‘there’s a lot to welcome’ in Reform UK’s plan. ‘It’s obviously going to be very important that we deport all the illegal migrants in the country and the next government has to make that their priority.’ He does criticise Farage’s suggestion that a Reform government would focus on deporting undocumented males, rather than women and children. ‘The people-smuggling gangs would exploit women and girls and it would encourage even more young men to pose as 15-, 16-, 17-year-olds,’ he says.

Jenrick does not stop there. On legal migration, he wants to outflank Farage and throw down the gauntlet to Badenoch. ‘Damaging though illegal migration is, legal migration is even more harmful to the country because of the sheer eye-watering numbers of people who have been coming across in recent years perfectly legally. It’s putting immense pressure on public services.’

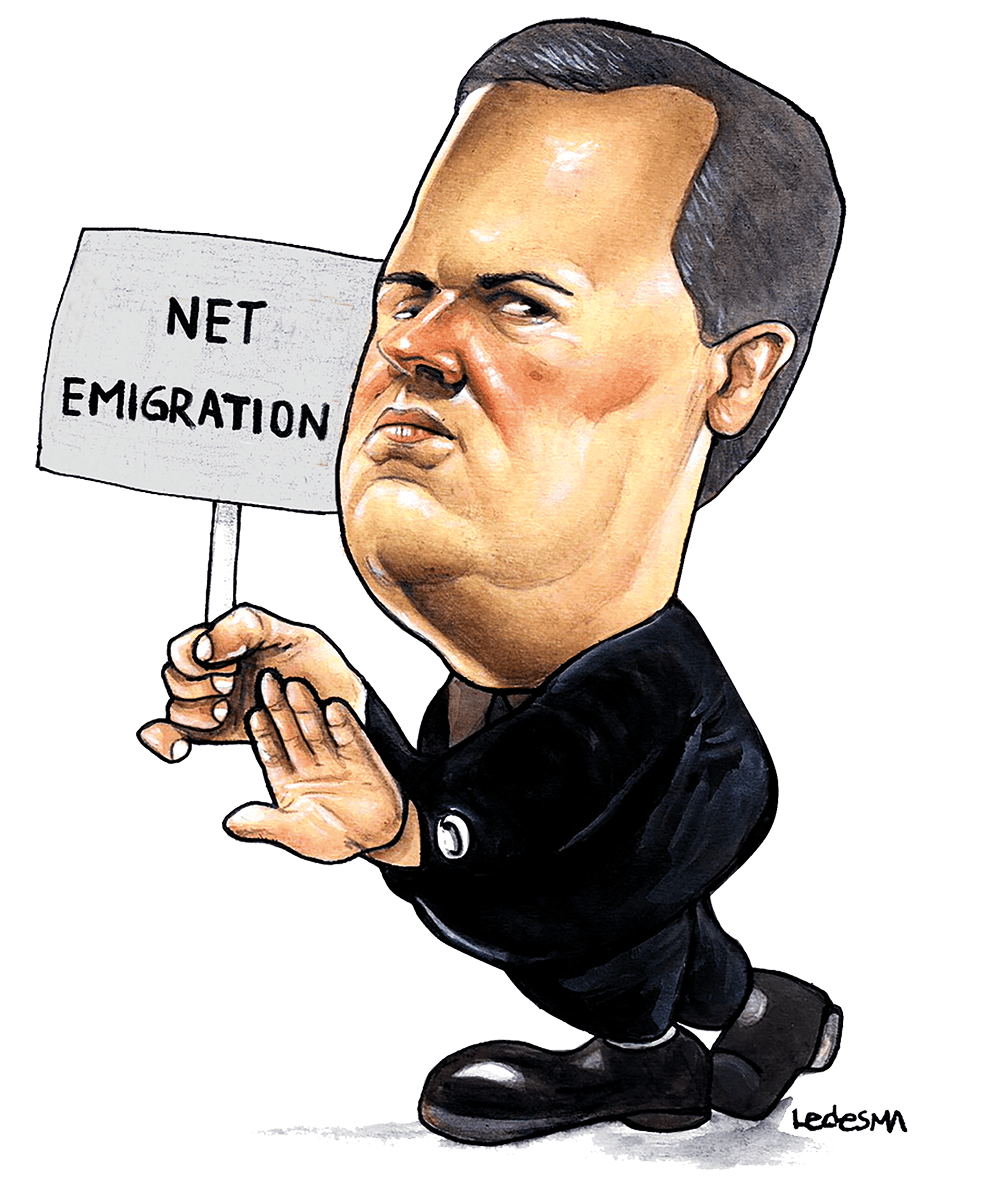

He calls for a return to the situation in the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s when the UK was a net emigration country. ‘I think the country now needs breathing space after this period of mass migration. The age of being open to the world and his wife, who are low-wage, low-skilled individuals, and their dependents has to come to an end. Reversing recent low-skilled migration will likely mean a sustained period of net emigration. I would support that.’

He points out that over 500,000 people left the country last year, so we would not have to close the border to reduce numbers. ‘Of course we stay open to the very best and brightest. We want the coders, the doctors, the serial entrepreneurs, the people who are clearly going to make a massive economic contribution to the country.’ How long would this last? A decade? ‘It could be, yes.’

Jenrick also says we need to ‘use every lever of the British state’ to remove illegals. ‘We need to suspend visas and end foreign aid.’ He points to the ‘convoluted negotiation’ between David Lammy, the Foreign Secretary, and Pakistan to return just three grooming gang members. ‘At the same time, we’re giving £130 million in foreign aid and tens of thousands of visas to Pakistan every year. That cannot be right. We should be open about the fact that we should send illegal migrants back to their home countries, even if in some cases those are inhospitable places.’

Badenoch has appointed Lord Wolfson, the best Tory legal brain in the Lords, to draw up her plan. Jenrick denies he is stealing his leader’s thunder by speaking now. ‘I fully support Kemi’s approach, which is to develop serious policies with detailed substantive basis behind them,’ he says, adopting a frown of sincerity. ‘That’s the way we can begin to rebuild public trust.’

‘My view is that mass uncontrolled migration has and is wrecking British culture and identity’

But he is also keen to pre-empt this document, criticising the suggestion by some senior Tories that the ECHR should be replaced by a British Bill of Rights. ‘My concern is that we will end up replacing activist judges in Strasbourg with activist judges in London, and we simply won’t get the benefits of leaving the ECHR,’ he explains. In his day job, Jenrick has called for new powers for politicians to ‘sack judges’ who are politically biased. ‘If you don’t have a plan to reform the judges, you don’t have a plan at all,’ he says.

Jenrick is not persuaded by the case for digital ID cards to remove illegals. His trip to Calais last month also convinced him that Labour’s new deal with the French to interdict the migrant boats won’t work. ‘Each and every one of the people in those camps is heading for the UK and they could be living in a hotel at the end of your street. Few spoke good English. Not a single person I spoke to said that they were fleeing persecution. They were all coming to the UK for economic opportunities. I literally saw a group of 40 or 50 migrants heading towards the main road holding life jackets, with people smugglers at the front and the back of the crocodile. They then caught a public bus to Dunkirk. The police, the local council – everybody knows it’s happening and no one is doing anything to stop it. The £800 million that we’ve given to the French is largely wasted. We have to take matters into our own hands.’

As immigration minister under Rishi Sunak, Jenrick came to believe that many of his colleagues, as well as the Whitehall system, were totally ‘out of touch’ with the views of the country. ‘At the Home Office I walked into a total bin fire. I think the points-based system that was created by the ministers at the time was the worst public policy mistake in my lifetime.’ By ‘the ministers’ he means Boris Johnson and his home secretary Priti Patel, who is now the shadow foreign secretary.

Asked what his moment of radicalisation was, he refers to a trip to Dover, where the then MP Natalie Elphicke took him to a housing estate overlooking the beaches. ‘Migrants were getting out of the boats, climbing up the hill, and residents were finding them in their garden or even their kitchen to steal food and drinks from their fridges. The anger and frustration of those people was absolutely palpable because they felt the Westminster elite didn’t give a damn about them.’

The same feelings were evident when Jenrick recently visited the protest outside the Epping hotel where asylum seekers are housed. ‘I met a single mum who had three teenage daughters. The oldest daughter, who was about to go to university, had bought some workmen’s boots and put them outside because she wanted the illegal migrants to think there was a man in the house.’

He goes further than Farage on the housing of asylum seekers. ‘They should be detained in camps,’ he says. ‘The facilities will need to be rudimentary prisons, not holiday camps. It’s not what Reform have suggested, which is cabins with a fence around them.’

Jenrick is married to a wealthy lawyer, Michal Berkner, and the couple were teased when he was housing minister for having four homes. But his emergence as a political player of note owes a lot to his upbringing in a working-class family in Wolverhampton and his parliamentary seat, Newark.

‘Both of my parents left school with very few qualifications. My dad became an apprentice. My mum was the secretary at Littlewoods in Liverpool. My dad set up a business, bought a white van and a tiny unit in Wolverhampton. There were more bad times than there were good times. The political class is unbelievably out of touch with the views of working people across this country, particularly in the types of places that I grew up in and represent today.’

‘Reversing low-skilled migration will likely mean a sustained period of net emigration. I would support that’

Newark is ‘full of exactly the same people like my mum and dad, hardworking, no-nonsense, patriotic people’ who are ‘absolutely sick’ of what he calls ‘asymmetric multiculturalism where we seem to take pride in every culture and identity other than our own’. He adds: ‘When I went to put up flags in Newark the other night, it wasn’t a question of counting the cars and the lorries in the vans that hooted their horns, it was counting the ones that didn’t.’

Two years ago, Jenrick wrote a memo to Sunak imploring him to use his conference speech to announce major cuts to legal migration or ‘we will continue to betray the unequivocal will of the British people’. He recalls: ‘It fell on deaf ears. I think Rishi, like others, was wrong on the economic arguments. I think, like a number of people, he didn’t see the social and cultural impact of legal migration. My view is that mass uncontrolled migration has and is wrecking British culture and identity.’

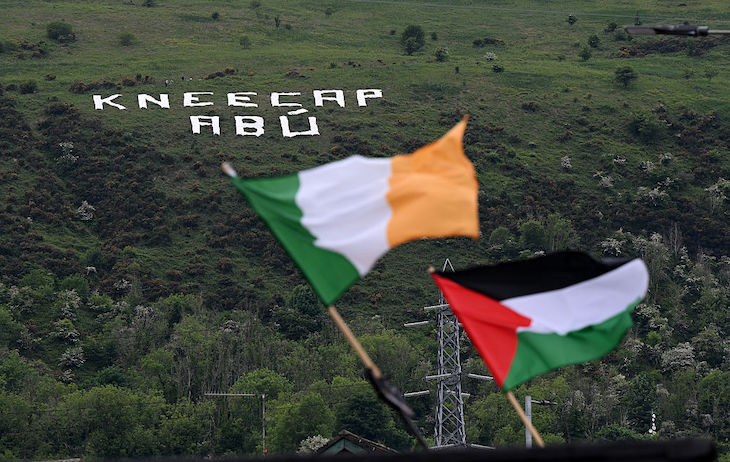

Another factor in Jenrick’s identity is that his wife is Jewish and his children are raised in both the Christian and Jewish traditions. ‘I do believe in God,’ he says. ‘But I’m not at church every Sunday. I take my children to church, my wife sometimes takes them to synagogue.’ This has shaped his views of the conflict in Gaza. ‘After October 7th, I was appalled by the protests that I witnessed on the streets of London. I didn’t view them as anti-Israel, I saw them as anti-British. I don’t want to live in a country where people take to the streets in apparent support of Hamas and Hezbollah or cheering the fact that the Houthis had fired missiles at British flagged vessels. Something’s gone very badly wrong with integration in this country.’

Wolverhampton was the adopted base of Enoch Powell, whose warnings about integration appear prescient in some regards. Jenrick has reflected on the notorious Rivers of Blood speech, but does not want Powell’s mantle. ‘The main lesson I’ll draw is that you have to persuade people of the arguments, not needlessly provoke them. You have to confront hard issues, but you’ve got to do so in a way which brings as many people with you as possible.’

Jenrick has used social media videos to do so very effectively. One in which he confronted fare dodgers on the Tube has been viewed 15 million times and is credited with a 50 per cent rise in fines. ‘People have such a low opinion of politicians that the way to overcome that is get out of a suit, get out of Westminster and take up the issues that are affecting everybody in their daily lives, and try to shame the authorities into action.’

His other presentational change was losing five stones in weight. After an unsuccessful dalliance with Mounjaro, he now runs three or four times a week and has ‘cut out all of the appalling junk food I used to eat – Chinese takeaways, McDonald’s at service stations on the A1’. He admits it is Michal who has been ‘telling me to get slim’. When did he last defy her? ‘I had fish and chips in the back of the car last week. I put the box in the bin outside the house. You can’t report that. She’ll find out.’ Whoops.

All this is not just window dressing. ‘The lesson of previous oppositions is that you have to demonstrate that you’re almost a different party to the one that came before,’ Jenrick concludes. ‘You do that by showing, not telling. It’s not enough just to do speeches.’ Your move, Kemi.

Comments