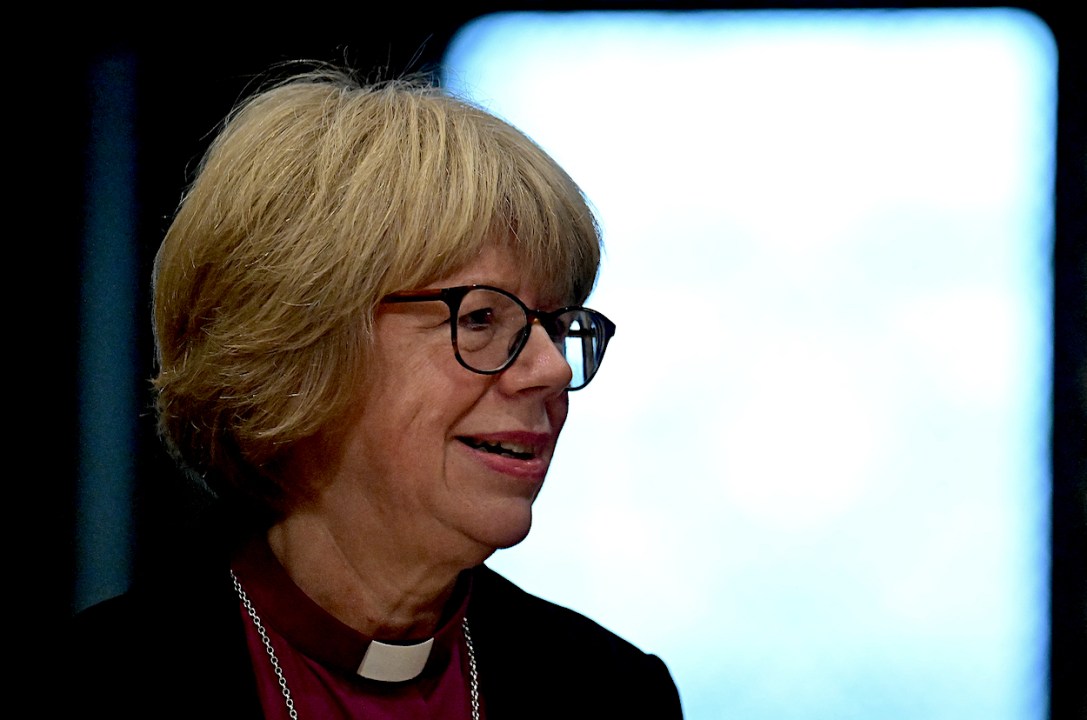

‘I look forward to spending the next seven years with you,’ said Bishop Sarah Mullally at the Diocese of London’s ‘Chrism Mass’ on Maundy Thursday this year. ‘Well, that’s her out of the race,’ said everyone – and everyone was wrong.

Perhaps this is a modern twist on the old nolo episcopari rule: that those being considered for episcopal office had to make clear they didn’t want it. Which, frankly, would be wise right now. As the Bishop of Gloucester put it, anyone wanting to be Archbishop of Canterbury ‘needed their head examined.’

The church is in a mess. It is deflated and downhearted; the old issues of female ordination and whether we can ordain or bless the marriage of homosexuals still foster great disagreements across the church. The sense that the congregation in the pews are seen as (at best) an irrelevance and (at worst) politically distasteful has led to a great gulf between the church’s leadership and its people. The vast flow of money towards pet projects of the centre, and the waste of money on politically unwise adventures, has put in stark relief the refusal to invest money keeping the church on the ground afloat. And ever-present after the resignation of Archbishop Welby is the reality of the church’s many safeguarding failings.

It is into this church that Bishop Sarah Mullally will be enthroned as the 106th Archbishop of Canterbury. Nobody doubts that she has a hard task ahead of her. It is eminently possible that she will not be able to steady the ship. She only has six years and that is not a lot of time. Three things, however, give me hope.

The first is that she is pastoral. On this I speak with experience: she has been my bishop directly for seven years. I have never known her not be at the other end of a phone if needed, or able to arrange a meeting with one of her clergy if requested. She was very kind when my father was dying, which is something you remember.

What stands out the most, though, was when I caught Covid just towards the end of lockdown, and found out on a Saturday afternoon. I sent out a frantic tweet asking if anyone was free to take the service the next day and, within 30 minutes, she had sent me a direct message on twitter offering her services – despite being on holiday at the time. She said that the theology that the bishop shares the ‘cure of souls’ with the rector of the parish was one that she took seriously.

I hope that our faith is a little stronger now

The second hopeful sign is that when she was leading the funding review for the Church of England this year, she ended up deciding to pump a lot more money into the poorest parishes under a scheme known as Lower Income Communities Funding. This could make a huge difference to the most deprived parts of the Church of England. It also indicates a willingness to trust local people to run their own parishes.

The third sign of hope is the vigour with which she has led the opposition to assisted dying in and outside the House of Lords. This is the first time I can remember the church really rallying together on a moral issue and she has gathered allies and marshalled support in a very clever and successful way. If she can focus her political energies on matters proper to the church and have the wisdom to step back from pontificating (literally) on those things which are, frankly, only her own political views, she could mark a sea change in the way the church is seen in the country.

When the disciples were in the boat and the storm brewed around them, they were sure that they would drown and found themselves admonished sharply by Christ as ‘men of little faith.’ I hope that our faith is a little stronger now, and that, with our trust in God, we will be led out of this storm to a calmer, more prayerful, future.

Damian Thompson and The Rev’d Marcus Walker react to the news on the latest Holy Smoke podcast:

Comments