The late squarson, Henry Thorold, was fond of pointing out that his Shell Guide to Lincolnshire was the bestselling of the series, not because of any intrinsic merit but because no guide to the county had been produced since the early 19th century. The same might turn out to be true of the latest volume of the Pevsner Architectural Guides, Dundee and Angus. The county, which changed its name in the 19th century, has not been described since Forfarshire Illustrated (1843) and the five volumes of Alexander J. Warden’s Angus or Forfarshire (1880-85). The book under review cannot quite claim to be the last ‘Pevsner’. Whilst most English counties are on their second and third edition there are still four volumes of Scotland yet to be published before the whole amazing enterprise that started in the 1940s is complete.

Few people know Angus. Sandwiched between the more touristical Perthshire, Fife and Aberdeenshire, it has remained L’Écosse profonde, a county of minor lairds, generally unspoilt towns and with a whale of an entrance at Dundee. Sir Walter Scott, impressed by its ancient families and Pictish remains, set The Antiquary in the locality.

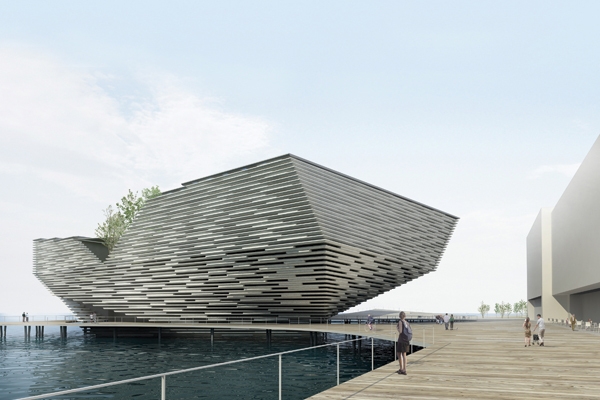

John Gifford’s volume is therefore something of a revelation. Dundee, one of the great 19th-century cities of Scotland and probably the saddest city in Britain during the 1970s, emerges as both the Cinderella and phoenix of the story. Few are aware of its rich churches by G. F. Bodley and Giles Gilbert Scott and, more surprisingly, good contemporary architecture, which includes Frank Gehry’s only work on these shores, the Maggie’s Centre. Dundee’s sink status was underlined by standing in for Moscow in Alan Bennett’s 1983 teleplay An Englishman Abroad. However, with Captain Scott’s ship, The Discovery, already established as a tourist attraction and the V&A on the way in 2015, Dundee is poised for revival.

The heart of the county is the rich vale of Strathmore, bounded on one side by a romantic coastline and the other side by the six Angus glens that skirt the edge of the highlands. It is château country; every couple of miles is the modest gate to a laird’s seat. The grandest castles still belong to the four Angus earls: Cortachy (Airlie),

Brechin (Dalhousie), Kinnaird (Southesk) and most famous of all, Glamis (Strathmore). Only the last is regularly open to the public and this partly tells us why Angus is so unknown: it remains a very private place which has never bothered to attract tourists. Montrose emerges as the finest town, with sturdy neo-classical public buildings. Arbroath, a once proud town, is not quite itself today and strewn with charity shops.

Dundee and Angus is admirably complete as far as descriptions of the buildings are concerned. John Gifford has done an exhaustive job of cataloguing the county inventory of churches, public buildings and houses. He has opened my eyes to many unexpected treasures such as J. Ninian Comper’s Church of St Mary at Kirriemuir.

What is missing is outside the Pevsner format: historical and literary associations. Barely a mention here of Walter Scott and nothing on the poet Violet Jacob at the House of Dun. The Declaration of Arbroath (1320) which defined Scotland’s independence of English claims, is mentioned, but not the infamous Earl Beardie, the 4th Earl of Crawford, the most colourful figure of Angus folklore who fled to Finavon Castle after the Battle of Brechin (1542).

Incidentally, it was a party at the 19th-century mansion at Finavon, given by Sir John Murray-Scott, that became the focus of the sensational law case in 1913 that settled the fate of the other half of the Wallace Collection on Lady Sackville. The Shell Guides relished such gossip, but then they never supplied the rigorous scholarship and original research that has gone into this much needed and overdue volume. One small cavil: in an otherwise exemplary description of my own house, Gifford has it facing the wrong direction.

Comments