Many art historians have written their own story of the making of an aesthete: Ruskin, Berenson and Kenneth Clark to name just three in the Anglo-Saxon world. The pattern varies, but typically it might include being bullied at school, a mentor, an epiphany in Italy, and the de rigueur discovery of Piero della Francesca.

The Eye has all the possibilities of being an appealing book in the same tradition — but for the author’s grating references to himself and his vocation as the ‘Eye’, as if this were some higher calling, a Glasperlenspiel in which the priesthood spends all day attributing Florentine paintings. ‘The Eye,’ we are informed, ‘is a miniature Christopher Columbus who roves over the world of art, alert to any surprises.’ Or these lines, worthy of Kahlil Gibran: ‘Though I was born with an Eye, I became an Eye… I am an Eye so that others can see.’ Craig Brown would have a field day. I began to imagine Thomas Chippendale referring to himself as ‘the Hand’. However, if one substitutes ‘art historian’ for ‘Eye’ the book becomes bearable and even enjoyable.

Who is Philippe Costamagna? He is the director of the Musée des Beaux-arts in Ajaccio, a respected specialist on Pontormo and Bronzino. Indeed, Costamagna’s book opens with his identification of a Bronzino Crucifixion in the Nice museum, an act of revelation that he compares to Claudel’s mystical conversion after hearing Vespers in Notre Dame.

Our ‘Eye’ comes from a cultivated bourgeois medical family that owned nice furniture and had family portraits painted by Renoir. There is a pleasing description of his early visits with his nanny to the smaller museums of Paris, his first artistic awakening when he visited André Malraux’s exhibition of the Musée Imaginaire at the Maeght Foundation in Vence, and later his attendance at the lectures of Michel Laclotte on Italian painting at the Ecole du Louvre.

As a graduate, the author was taken with the study of Florentine portraiture, and so he began to play the attributions game. Costamagna travels the world to see paintings in his chosen field: he must be a man of considerable charm and vitality, as every door opens for him. His big break comes when an enterprising publisher asks him to write the catalogue raisonné on Pontormo. The transition from idealistic research student to 16th-century expert and art magus is entertainingly described, and another chapter on his various art discoveries comes close to being enthralling.

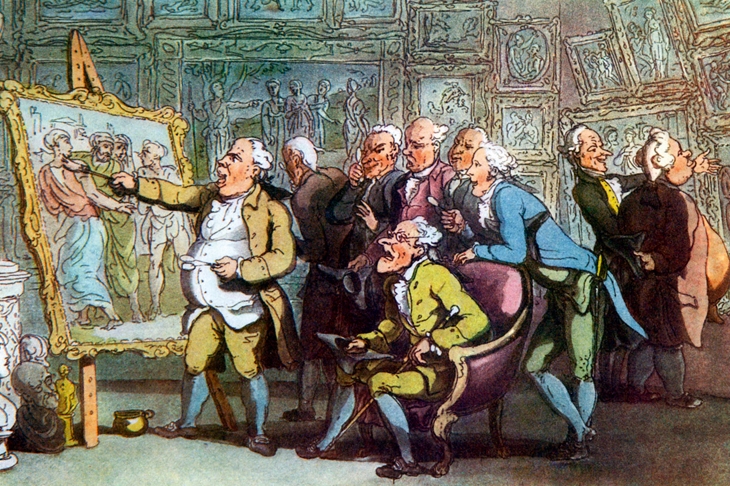

The central story of the book is the rise and fall of Eyes: ‘I am, after all, a member of only the fifth generations of Eyes’, for which in this context one must read connoisseurs. Art historians come in many different forms: those interested in social context, subject matter, documents, or in authorship: which is where Costamagna comes in. Connoisseurship as a system of classification was invented by a 19th-century Italian art historian, Giovanni Morelli, who taught anatomy at the University of Munich, and began to apply a similar comparative method to the study of paintings, analysing details such as hands and drapery in what was at first disparagingly dubbed ‘the ear and toenail school’. The results, however, were spectacular, and the greatest player was of course Berenson, who led the field in the golden age of ‘the Eye’.

Connoisseurship has had a bumpy ride over the last 100 years, as its close relationship with money and the art trade lead to the inflation of the artist’s oeuvre. ‘The Eye,’ observes our author, ‘must recover the nobility of our métier that has been lost.’ At this point I find myself longing for football hooligans. Costamagna never met Berenson — both hero and villain in this narrative — but is haunted by him, and by his younger Italian colleague, Roberto Longhi. One of the author’s mentors is the monstre sacré, Frederico Zeri, an art expert who became associated with Paul Getty, but failed to benefit materially from the connection to the same extent that Berenson did from Duveen. Costamagna admires these titans, even though he considers they were morally compromised. Today, he believes, connoisseurs are a threatened species outside Italy — ‘traditional art historians don’t recognise Eyes.’ He has a point here.

Nicholas Penny recently wrote a brilliant article on the subject, highlighting the consequences of this, including the purchase of the Bolton forger’s Egyptian Princess. Art historians trained from books without handling works of art are certainly at a disadvantage. However, those in the acquisition business, be they museums, collectors or dealers, still depend on these skills, so although they may go out of fashion they will always be required. And who knows — a young art historian seeing what fun Costamagna has had in this field may feel inspired to follow.

Comments