The central themes of Russian history have remained constant for over a millennium. Russia’s vast spaces and lack of any natural borders have always made her inhabitants terrified of invasion. And to protect the country against invaders, and to preserve its unity, Russia’s rulers seem always to have felt it necessary to assert their authority with great brutality. All this is at least hinted at in the very first introduction to Russian history. The Primary Chronicle, compiled in Kiev around 1113, tells us that

there was no law among [the Slavs], but tribe rose against tribe… Accordingly they … said to the people of Rus [who were probably Scandinavians]: ‘Our whole land is great and rich, but there is no order in it. Come to rule and reign over us.’

So began the Rurik dynasty, rulers of the state of Kiev Rus until the Mongol invasion.

Geoffrey Hosking’s beautifully written volume is less than a fifth of the length of Bushkovitch’s. Hosking, however, has an unerring sense of what truly matters, and it is he, not Bushkovitch, who quotes this crucial passage in full. It is the same with regard to art, music and literature; where Bushkovitch merely provides lists of events, Hosking gives us significant details and real insights.

It is Hosking who devotes most space to one of the most crucial works of 20th-century Russian art, Malevich’s ‘Black Square’, painted in 1915. Hosking helps the reader to grasp the extent of Malevich’s metaphysical ambitions by captioning the reproduction: ‘The vacant icon’. And he quotes Malevich at his most grandiose: ‘The white free chasm, infinity is before us!’ Bushkovitch’s account of ‘Black Square’ is, by contrast, absurdly understated: ‘Kazimir Malevich began to turn towards full abstractionism.’

Similarly timid understatements vitiate much of Bushkovitch’s book. Here, for example, is what he writes about the Terror Famine in Ukraine in 1932-33, which brought about the death of between three and five million peasants: ‘The famine disturbed the authorities, but they did very little about it. Stalin did not take any extraordinary methods against the famine…’ This is extraordinarily bland: the only remaining argument about the famine is to what extent Stalin simply allowed it to happen, and to what extent he undertook extraordinary methods not against it, but in order to bring it about. Here again, Hosking says much more in fewer words:

The [collectivisation] campaign became enmeshed with the suspicion that Ukrainians might favour treacherously leaving the USSR and joining Poland. Hence the ‘holodomor’, the hunger-famine which many Ukrainians today judge a form of genocide.

Hosking follows this with an account of another tragedy that Bushkovitch does not mention at all: the collectivisation of the largely nomadic peoples of Kazakhstan brought about the death or emigration of around one third of the republic’s population. Hosking gave the Reith lectures in 1988; he has written at least four important works of Russian history and he is a master storyteller. I cannot recommend this book too highly.

During the last few months, Putin’s regime has, for the first time, begun to seem vulnerable. Both books were completed before the recent wave of mass protests. Nevertheless, given the continuity of Russian history, it is reasonable to ask if they offer any pointers as to the nature of Russia’s future.

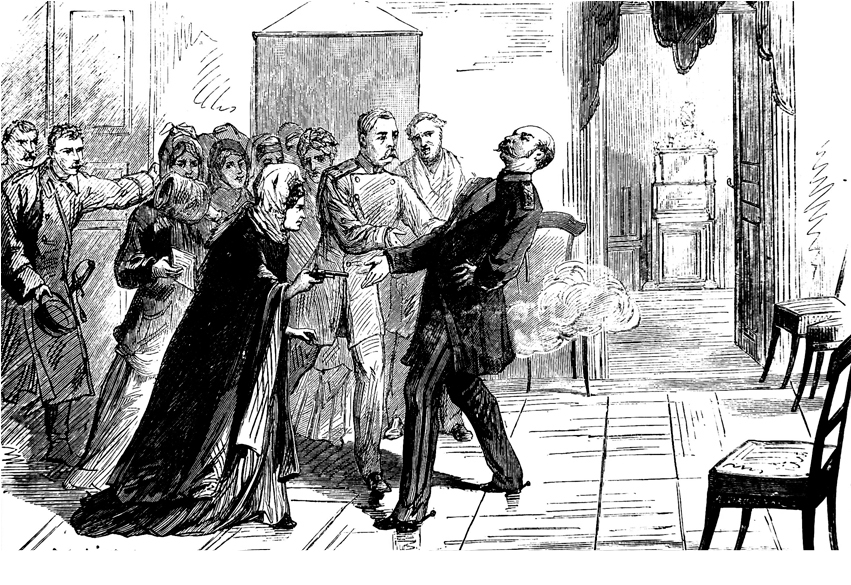

For several decades before the Revolution, civil society was, by and large, at odds with the autocracy. The intransigency of the autocracy is common knowledge, but a broad swathe of civil society — not just a few committed revolutionaries — seems to have been no less intransigent. Hosking tells how, in 1878, a young revolutionary, Vera Zasulich, shot and wounded the notoriously brutal Governor-General of St Petersburg:

No one denied that she had attempted murder, but to applause in the courtroom, the jury acquitted her on the plea of her lawyer that she had ‘no personal interest in her crime’, but was ‘fighting for an idea’.

The jury’s blithe disregard for the law made me think of a passage in a recent Chatham House paper by the political analyst Lilia Shevtsova, the author of several books about Yeltsin’s and Putin’s Russia:

The new Russia has to move from fighting to gain a monopoly on power to the struggle against the very principle of monopolised power. That will help Russian society abandon its centuries-long search for a leader-saviour and realise that it needs fixed rules, not fixers.

In 1878, let alone in 1917, few people seem to have taken seriously the idea of fixed rules. Whether or not this has yet changed may well be a determining factor in Russia’s future.

Hosking makes no claims to prophetic gifts. Nevertheless, his guardedly optimistic conclusion deserves quotation:

Russians are better educated than in the past, and they have incomparably more experience of life outside their own country … The age-old justification of authoritarianism — that the country faces powerful external threats — is no longer persuasive. The gap between rulers and ruled is widening once more. Russia is one of the world’s great survivors, and it will probably cope in its own way with these challenges. How it will do so is at the moment impossible to say.

If Hosking had had the chance to write an epilogue to his book, he might have added that Putin is, in fact, still doing his best to exploit the spectre of external threats; in a recent speech at a football stadium he quoted from a famous poem about Borodino, the battle immediately preceding Napoleon’s entry into Moscow in 1812.

Comments