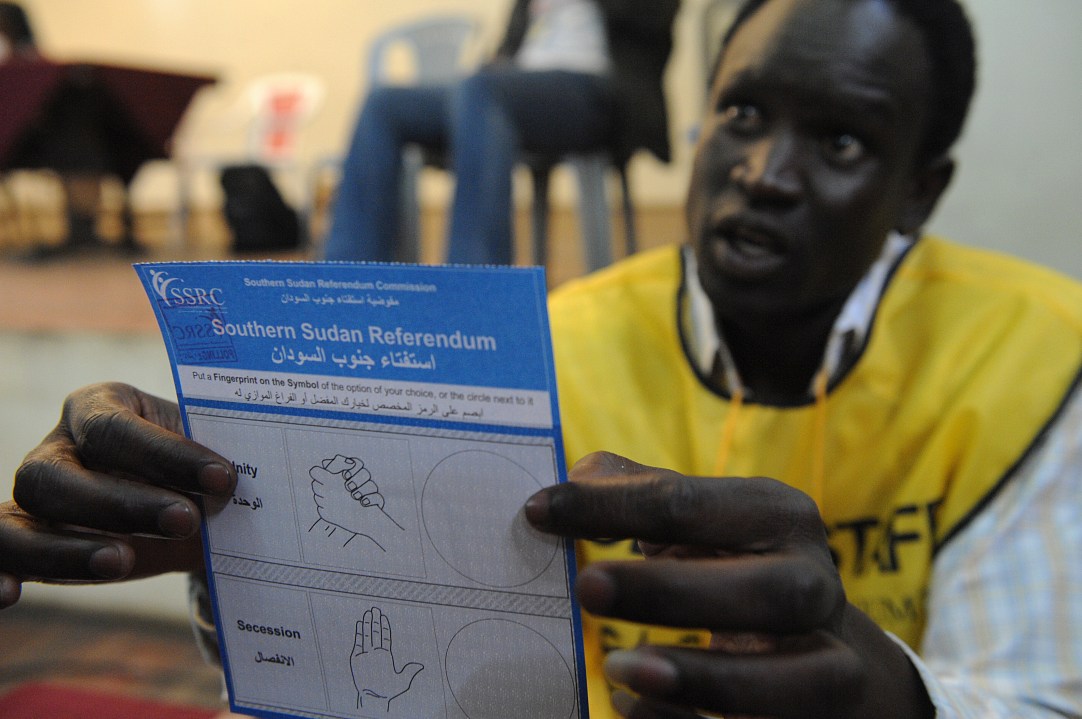

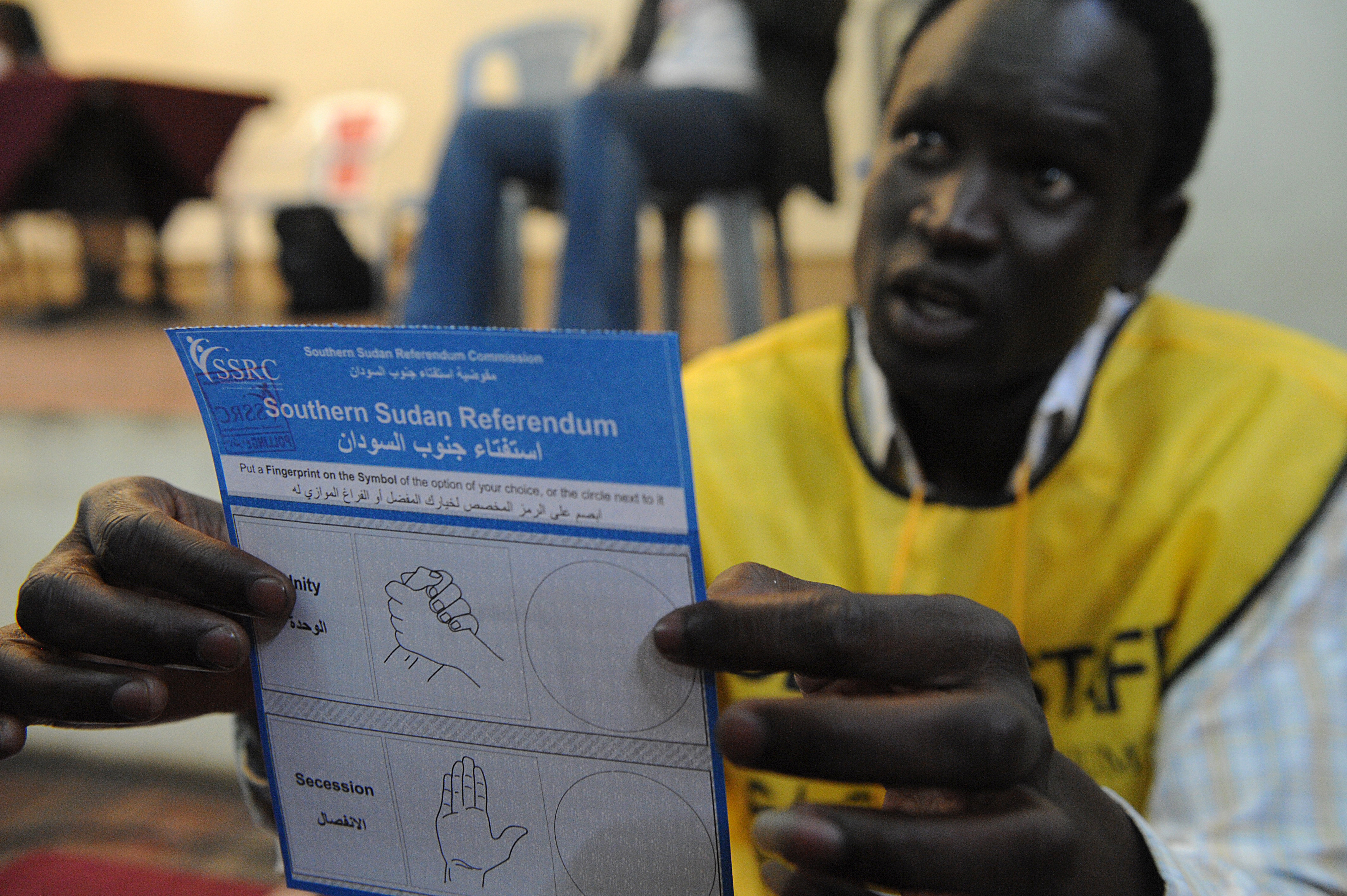

Today, voters in the southern part of Sudan head to the polls in a referendum which will determine whether they should form their own state or remain part of Sudan, Africa’s largest

Today, voters in the southern part of Sudan head to the polls in a referendum which will determine whether they should form their own state or remain part of Sudan, Africa’s largest

country. Secession – the most likely outcome of the referendum, and called for in the 2005 peace agreement that ended 21 years of civil war between the country’s north and south – would

mean that the government in Khartoum could lose not only territory, but also over 80 percent of the revenues it receives from oil exportation, as most of the oil is located in the would-be state of

South Sudan. As a result, many fear that bloodshed will follow the poll.

Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir – the only serving head of state wanted by the ICC on war crimes charges – has, in the last couple of days, played down the risk of conflict. A visit to

Juba, the capital of South Sudan, went off without any problems. But in an interview with Al-Jazeera TV on Friday, he seemed to back-track a little, issuing warnings about the fate of southern

Sudan should it choose to separate. And at least nine people have died during attacks on southern Sudanese troops, ahead of today’s referendum. Gunmen targeted the Southern Peoples’ Liberation

Army, or SPLA, late Friday and early Saturday.

Even if the referendum takes largely place peacefully, even if the people of southern Sudan vote for independence, and even if the Khartoum government accepts the result, South Sudan is going to

face many years of hardship. Riven by factions who were brought together to fight against the Khartoum government but have no common, post-independence ideology, the new government will struggle,

and life will be hard for the newly-independent people. But, as in Kosovo, Montenegro, Eritrea, South Ossetia, and even Ukraine, that may be a price the South Sudanese are willing to pay.

The international community has also done more to prepare for various eventualities than in the run-up to many other conflicts. International Development Secretary, and the British Cabinet’s

resident Sudan expert, Andrew Mitchell has allocated millions for relief programmes in case conflict breaks out and a humanitarian crisis ensues. Massachusetts Senator John Kerry, head of the

Foreign Relations Committee, is now on his third trip to Sudan on behalf of President Barack Obama.

Nonetheless, the next few days will determine not only the fate of south Sudan but also whether a conflict that cost 2 million lives and became Africa’s longest civil war will resume once again, or

if separatist movements in Morocco, Mali, Niger, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Nigeria will seek to emulate the South Sudanese.

Comments