The Easter Sunday massacre in Sri Lanka, which targeted churches and hotels, has so far claimed 310 lives and left a further 500 people injured. National Thowheed Jamath, a local Islamist group, has been implicated but authorities believe it received support from an international terrorist organisation.

Colombo has declared a state of emergency and rounded up 40 suspects but the government’s swift response belies its behaviour before the atrocity. US and Indian intelligence reportedly warned of an impending attack earlier this month and a domestic police memorandum dated April 11th flagged up ‘an alleged plan of suicidal attack’; it also asked ministerial, judicial and diplomatic security divisions ‘to provide special security measures to the areas covered by your division’. Sri Lankan minister Harin Fernando says ‘serious action need[s] to be taken as to why this warning was ignored’.

These weren’t the only alarm bells. The situation for Sri Lanka’s 1.6 million Christians — mostly Catholics — has been perilous for some time now. Open Doors, an American organisation that monitors Christian persecution, compiles an annual watchlist of the 50 worst countries to practice the faith. States are ranked by the intensity of maltreatment — high, very high and extreme — and last year Sri Lanka placed 46th. Open Doors identified ‘religious nationalism’ as the cause of anti-Christian activity and had this to say about the situation:

‘Those who convert to Christianity from a Buddhist or Hindu background are subject to harassment and discrimination by family and community. They are put under pressure to recant Christianity. Additionally, Christian churches are frequently targeted by neighbours, and local officials sometimes demand they close their buildings, which they regard as illegal. This repeatedly leads to mobs protesting against and attacking churches, especially in rural areas.’

That this latest attack appears to be the work of Islamists only underscores the multiple fronts on which Christians in the developing world are vulnerable.

If the Sri Lankans have questions to answer, so do the rest of us. Anti-Christian terrorism and persecution outside the West seldom piques our interest. (Nor, it must be said, does terrorism against Muslims.)

Last year, in Open Doors’ 50 worst countries, 4,136 Christians were killed because of their religion — 11 every day. In the same reporting period, 2,625 Christians were arrested, detained without charge, or imprisoned and 1,266 churches or other Christian buildings were attacked. The number of Christians who experience high levels of persecution has risen 14 per cent in a year, taking the number to a staggering 245 million. Globally, one in every nine Christians is a victim of persecution.

The sharp increase is thanks to the spread of Islamism in sub-Saharan Africa, additional anti-Christian laws and campaigns targeting Christian women in particular. Repression continues in dictatorships like China and North Korea and violent Hindu nationalists are allowed to brutalise and intimidate India’s Christians ‘with what seems like no consequences’, according to Open Doors.

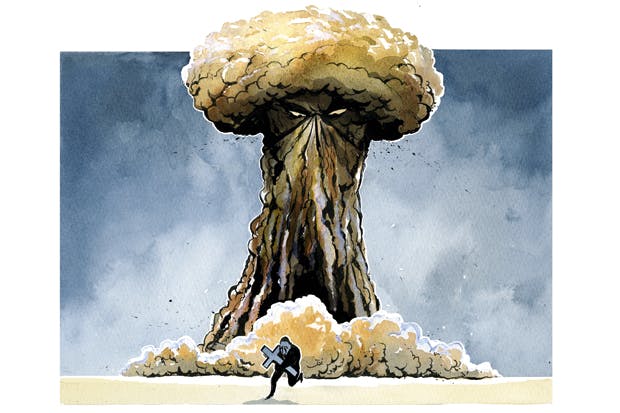

Whether conducted by Islamists, totalitarian atheists or religious nationalists, we are witnessing a global war on Christians. Only we don’t seem all that interested in witnessing it. Apart from massacres like the one in Sri Lanka, news about tyranny or terror against Christians seldom makes it past the foreign page — if it makes it there in the first place. Theresa May’s Easter message touted her government’s review into the issue but the scale of action — to say nothing of public and elite outrage — is many factors smaller than the scale of the threat. The survival, freedom and dignity of Christians in non-Western countries is a great moral challenge for our times. Our indifference is indefensible.

If you want people to care about something, you need to give it a name. Christians are victims of the extremists blowing up their churches but also of that progressive near-sightedness that only sees villainy in the West. Persecution of Christians can’t readily be linked to US foreign policy and so it fails to stir attention.

In 2003, the late political theorist Kenneth Minogue advanced the term Christophobia to describe anti-Christian prejudice. The term never really took off, though it continues to be used by some Christians. We should always be wary of ideologues who stick ‘phobia’ on the end of their beliefs and declare themselves victims of those who disagree. Christophobia does not describe mere secularism or atheism but, in Minogue’s words, ‘quite visceral hatred of this apparently declining set of beliefs’.

While Minogue concerned himself with an increasingly intolerant Western liberalism — which has no doubt contributed to apathy about non-Western persecution of Christians — ‘Christophobia’ describes the intolerance faced by Christians and their religious liberty around the world. Christophobia, to borrow a definition from elsewhere, is rooted in prejudice and is a type of prejudice that targets expressions of Christian-ness or perceived Christian-ness.

It may take the form of terrorism; state repression; political, social or employment discrimination; incitement to violence; or incursions on freedom of conscience or practice. Christ told his disciples: ‘And ye shall be hated of all men for my name’s sake: but he that endureth to the end shall be saved.’ Those enduring the very worst persecution should not endure it alone. Only by acknowledging the scourge of Christophobia and applying legal, diplomatic and financial sanctions to countries that practice or permit it can we hope to improve the lives of millions of Christians.

Comments