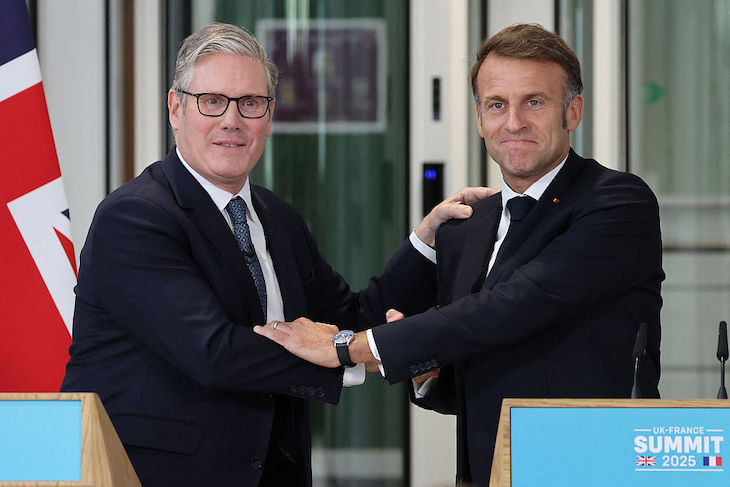

There was a sense of déjà vu to today’s announcement by Keir Starmer that he intends to ‘secure’ Britain’s borders. Standing alongside Emmanuel Macron, the Prime Minister pledged ‘hard-headed aggressive action on all fronts’ to crack the migrant crisis but warned that there is ‘no silver bullet’.

The sceptic might argue that the real problem in cracking the migrant crisis isn’t the criminal gangs but the human rights industry

Rishi Sunak deployed the same phrase in March 2023 when, as Premier, he stood alongside the French president, and promised to take back control of Britain’s borders. He failed, and few have faith in this new ‘one-in one-out’ scheme.

‘Migrants arriving in a small boat will be detained and returned to France in short order,’ explained Starmer. ‘In exchange for every return, a different individual we have allowed to come here by a safe route, controlled and legal.’

The pilot scheme will begin ‘in the coming weeks’ and is expected to entail 50 migrants being sent back each week. So far this year, 21,000 have crossed the Channel in a small boat, including around 220 today. The PM believes in his plan, stating that it will ‘break the gangs’ business model’.

The sceptic might argue that the real problem in cracking the migrant crisis isn’t so much the criminal gangs as the human rights industry. As the BBC pointed out: ‘Any attempt to return people who have claimed asylum in the UK to France will trigger a challenge in the courts’.

When Starmer gave his ‘Island of strangers’ speech in May, with a promise to tighten immigration rules, there was an immediate outcry. More than 100 charities and civil society groups signed a protest letter to the government warning of the ‘profound consequences for the people we serve’.

There are other obstacles to surmount to implementing successfully the one-in, one-out scheme – namely, the objection of several EU countries, among them Italy and Spain, who worry that any migrants returned from Britain will eventually end up on their patch.

In June 2026, the EU will have its vaunted Pact on Migration and Asylum fully operational, what it describes as a ‘set of new rules managing migration and establishing a common asylum system at EU level.’

Note the word ‘managing’; not reducing or stopping, but managing. Put another way: the migrants will keep coming but they will be more evenly dispersed among member states. Any country that objects could be slapped with a €20,000 (£17,000) fine for every migrant it refuses to accept.

The deal has been years in the making and the last thing Brussels wants is the troublesome British undermining its new rules with a scheme of its own. Perhaps that’s what Macron was hinting at on Wednesday evening when he addressed the Guildhall.

‘The European Union was stronger with you and you were stronger with the European Union,’ cooed the president. He returned to the theme during Thursday afternoon’s press conference, saying: ‘Since Brexit the UK has no migratory agreement with the EU, nor a readmission scheme…Precisely the opposite of what Brexit promised.’

Macron want Britain back in the EU and a first step might be signing up to the EU’s Pact on Migration and Asylum before it is launched next June. Of course, the EU’s Pact won’t make much of a dent on the vast numbers of people desperate to start a new life in Europe, and nor will this latest Anglo-French venture.

Does anyone seriously believe that the two most culturally left-wing leaders in their countries’ history want to clamp down on free movement? Macron joined the Socialist party at a young age and, in 2017, he declared that ‘there is no French culture. There is a culture in France. It is diverse.’

He has allowed far more legal and illegal immigrants to arrive in France than his predecessor, the openly Socialist Francois Hollande. At the start of this year Le Figaro ran an article headlined ‘France’s doors have never been so open’, a chronicle of how migrant numbers have soared during Macron’s eight years in power.

Some of their fact were pulled from a 2024 Senate report. Annual asylum applications were at a record high (142,649) and it noted that ‘four million residence permits were valid at the end of 2023, compared with 2.7 million in 2013’.

Senators who once supported Macron, like the centrist Nathalie Goulet, have lost faith in the president. Last December, she denounced ‘an immigration business’, an ecosystem of NGOs and law firms that did very well out of the migrant crisis. ‘More than a billion euros in subsidies are paid by the State to migrant aid associations,’ she said.

The conservative interior minister, Bruno Retailleau, shares Goulet’s dismay at the amount of money channelled into these associations; last October he demanded that they ‘act in coherence with the State’.

This is the reason why Germany recently announced it was cutting off the financial tap to NGO migrant vessels in the Mediterranean. ‘I don’t believe it is the foreign office’s job to use funds for this type of sea rescue,’ said Foreign Minister Johann Wadephul.

Retailleau has scored one small success this week. A bill tabled by his centre-right Republicans has been signed off by the Senate and parliament; as a result, foreigners awaiting deportation can now be held in detention for to 210 days, up from 90 days.

Retailleau and Macron are not friends. One is a conservative and the other a progressive. Last October, a month into his job as interior minister in the coalition government, Retailleau declared that immigration was ‘not an opportunity’ for France.

This drew a curt retort from the president, who described Retailleau’s remarks as ‘resolutely at odds…with reality’. He added: ‘There are millions of dual nationals in our country, at least as many French people of immigrant origin, and at least as many people of immigrant origin. It’s our wealth, it’s our strength.’

Keir Starmer has in the past boasted that ‘our nation’s diversity is one of its greatest strengths’. That is what he and Macron really agree on – not smashing the gangs and stopping the boats.

Comments