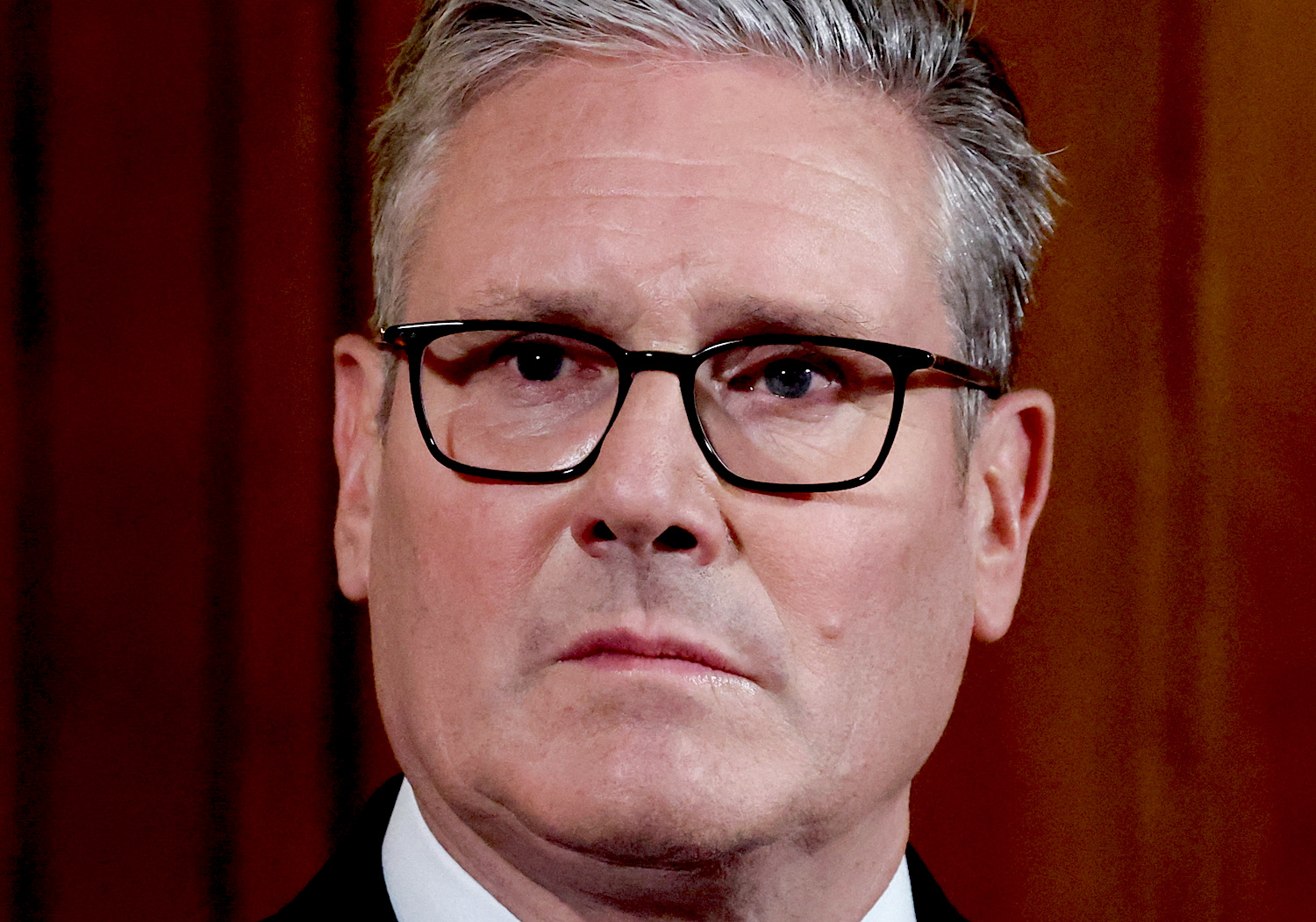

Britain has formally recognised a Palestinian state for the first time. The Prime Minister Keir Starmer said his announcement yesterday keeps ‘alive the possibility of peace’. Given Britain’s history in the region the move is deeply symbolic, even if it is unlikely to change the reality on the ground. Britain will recognise a country with whose past it is deeply enmeshed and correct a historical injustice. But Starmer would do well to learn from Britain’s involvement with Palestine a century ago: promises and words are cheap, a viable two-state solution will require more.

Seventy-seven years after the last High Commissioner left Palestine, his vision of two states for two peoples seems as far away as ever

On 14 May 1948, General Sir Alan Cunningham, the last British High Commissioner for Palestine, lowered the British flag at the port of Haifa. As he stepped onto his launch, leaving the shores of Palestine for the last time, his lean, gentlemanly face betrayed little emotion. Boarding the cruiser Euryalus waiting just offshore, he awaited midnight when the British Mandate in Palestine would officially end. Compared to the ceremony and fanfare that had accompanied Cunningham from Government House in Jerusalem to the port of Haifa, the final few hours were markedly quieter. At midnight, the cruiser simply hoisted its anchor and slipped quietly away to Cyprus.

Three decades of British rule had just come to an end. Vanquishing the Ottomans in 1917, Britain had vowed to help facilitate a ‘Jewish national home’ in Palestine, while at the same time promising that such efforts would not ‘prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.’ These words, first articulated in the Balfour Declaration of 1917, were enshrined in the terms of Britain’s Mandate which was received from the League of Nations, and came into effect in September 1923. Thus began over 30 years of wrangling and policy drift as successive governments sought to rule the country, while finding a way to honour these two seemingly contradictory promises to increasingly fractious Zionist and Arab Palestinian nationalists.

Eventually, this balancing act became too much. Barely two months after departing the country, Cunningham had told an audience at Chatham House: ‘I sincerely trust we can feel that we left with dignity, using all our efforts to the last for the good of Palestine.’ But by this time ‘Palestine’ no longer existed as a state. After months of attempts to simply get Jews and Palestinian Arabs to the negotiating table to discuss the future of their country in 1946-7, the Attlee government, exhausted and frustrated, decided to hand the country’s fate to the nascent UN.

While Cunningham was busy helping to oversee the British departure, representatives from the then 57 nations of the UN met in New York, with a majority voting to adopt Resolution 181: the portioning of Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state – a two-state solution. Britain abstained from voting, signalling that it was relinquishing control of the issue and unwilling to enforce partition as a departing power – especially as most of the Arab states with whom Britain wished to maintain good relations were against the resolution. Nevertheless, it was a solution to Jewish and Arab national ambitions which Cunningham and many in the Colonial Office had long advocated as being amongst the only workable and just solutions.

But only one of these states emerged. As Cunningham was departing, David Ben-Gurion, the head of the Jewish National Council, had declared the creation of a Jewish Israeli state at a ceremony in Tel Aviv. When the surrounding Arab states declared war on the new Jewish state, Arab Palestinians were caught in the middle. With their political leadership fractured and dispersed, Palestinians were the greatest losers of the First Arab-Israeli War. Around 750,000 Arab Palestinians became refugees as Israel seized land allotted by the UN to an Arab state in Palestine, expelling entire communities, while Egypt and Jordan seized Gaza and the West Bank respectively.

Britain’s departure thus presaged the beginning of one of the most contentious and enduring geopolitical issue of the 20th and 21st centuries: the fate of Palestinian refugees and the right of the Arab Palestinians to self-determination. Since 1967, Palestinians have lived under Israeli occupation after Israel conquered the territories from Egypt and Jordan during the Third Arab-Israeli War.

Seventy-seven years after abstaining on Resolution 181, Britain will now recognise two states in the territory. As the Prime Minister made his announcement at the end of July, David Lammy, attending a UN conference on Palestine, told assembled delegates that ‘there is no better vision for the future of the region than two states.’ Alluding to Britain’s past in the country, Lammy stressed that with ‘the hand of history’ on its shoulder, Britain would recognise a Palestinian state and correct ‘a historical injustice.’

While Starmer acted in concert with French and Canadian allies, thus increasing the impact of the announcement (and the scale of anger in Jerusalem), it is Britain’s recognition which has the largest symbolic importance. As the former power in the territory, traces of British rule can still be seen all over Israel and Palestine: from bright red post boxes dotted around cities such as Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and Nablus, often complete with royal cipher; to the large ‘Tegart forts’ which were built as fortified police stations – a function many still serve for both the Israeli and Palestinian Authority police forces today (although their uses are as diverse as a day care, restaurants, and a maximum security prison).

Generations of Palestinians have grown up surrounded by the paraphernalia of a power that once ruled over them, left them to their fate after failing to live up to its promises, and then refused them national recognition for three-quarters of a century. Now that wrong is being righted. Although most Palestinians across Gaza and the West Bank feel rightly that Western states’ recognition of Palestine will not change much on the ground, many welcome Britain’s decision as a symbolic act and a move to atone for an imperial failure.

But symbolism alone means little. Opposition parties are right to point out that statements without workable policy will do little to solve the situation. There is a humanitarian crisis in Gaza, senior officials in Israel speak of cleansing the territory, and recently announced plans to expand West Bank settlements would strip more land from Palestinians and ‘practically erases the two-state delusion’ as the Israeli Finance Minister recently crowed.

Recognition will remain a purely symbolic gesture. A possible Palestinian state is being systematically eroded and erased by Israel, while the British government shows little willingness or ability to challenge this reality. Starmer risks making the same mistake Britain did during the Mandate – offering words and promises without substantive action. Seventy-seven years after the last High Commissioner left Palestine, his vision of two states for two peoples seems as far away as ever.

Comments