No Californian could have painted Hockney’s pools. No La-La Land artist, raised on sun and orange juice, would have done tiles and diving boards and tan-lined bottoms as the boy from Bradford did.

It had to be a Hockney, brought up, the fourth of five children, in a two-up two-down. Hockney, who aged three had sheltered from bombs with his mother Laura, father Kenneth, four siblings and a lady neighbour in the cupboard under the stairs. A Yorkshire child steeped in Typhoo tea and fortified by meat and potatoes from Robert’s Pie Shop. A painter who had bicycled the Wolds in the rain, and lived in the garden shed of an Earl’s Court boarding house when a student at the Royal College of Art in London.

‘I was brought up,’ he said, ‘in Bradford and Hollywood.’ He had seen Los Angeles in Technicolor, brighter than bright, in Singin’ in the Rain on trips to the pictures. The first time he saw the city for real, in 1964, aged 26, his first impression was of pool after pool: ‘As I flew over San Bernardino and saw the swimming-pools and the houses and everything and the sun, I was more thrilled than I have ever been in arriving in any city.’ ‘A Bigger Splash’ (1967) is no belly flop, but an ecstatic head-first dive into light, sun, pinks, blues, palms, sprinklers, days so hot you might as well never get dressed. At the Royal College he had worn vest, shirt, tie, cardigan. In LA, a man could lie flat-out naked on a white towel on the pool flagstones or on a bed in just T-shirt and socks.

You’ve seen it before, the splash, in Tate’s permanent collection, but here, in the fourth room of the gallery’s retrospective, which spans 60 years of work, it comes like a baptism: a washing off of England, where Private Eye in 1963 was running features like ‘How To Spot a Possible Homo’ and where Hockney had to keep two coal fires burning to get his basement flat warm. ‘A Bigger Splash’ is a squiggle-wiggle, pool-side, total immersion in beaches, boys and Mulholland Drive.

As a schoolboy, Hockney had gone up to London to see Piero della Francesca’s ‘The Baptism of Christ’ (c.1450) at the National Gallery. It appears in miniature in two of the paintings in the Tate show: pinned to a board behind curator Henry Geldzahler in ‘Looking at Pictures on a Screen’ (1977), and reflected in the mirror between Laura and Kenneth in ‘My Parents’ of the same year.

He must also have seen Carlo Crivelli’s ‘The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius’ (1486). His ‘California Art Collector’ (1964) borrows the Crivelli composition with the collector wearing the Virgin’s green, and her covered sculpture pavilion replacing Crivelli’s cutaway Renaissance palace. The swimming-pool and palms in the top-left-hand corner play the part of the divine message from the heavens: the California pool as God. (This from the son of a Methodist lay preacher.)

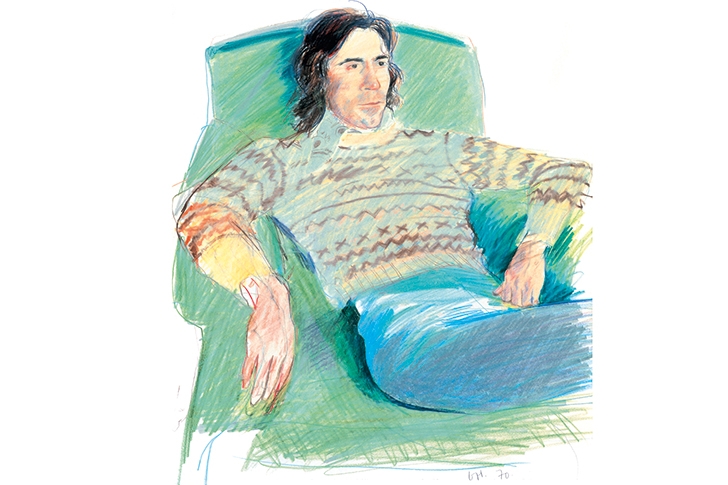

It is a dazzling show. Tate have gone bananas — you’ll have these on the brain after seeing Hockney’s double portrait of Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy (1968) with its eye-popping fruit bowl and cob of sweetcorn — for colour. No artist was ever less suited to a white cube. The walls of the early rooms are pink — the recurring pink of the vase and work table in ‘Model with Unfinished Self-Portrait’ (1977), and of the sofa in the portrait of ‘Henry Geldzahler and Christopher Scott’ (1969). Then the walls turn grey — colour-matched to Ossie Clark’s collar and coffee table in ‘Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy’ (1970–71) — and burgundy in the room of Hockney’s drawings. These celebrate Hockney as not just a colourist, but as a consummate draughtsman and doodler too. With what economy he sketches ‘Peter Langan in his Kitchen at Odin’s’ (1969) or his mother wearing her hat and coat indoors (1978), and with what illusionistic trickery he crayons the rippling, shifting, treacherous geometry of the tiles in ‘Study of Water, Phoenix, Arizona’ (1976).

Hockney’s etchings are missing from Tate. For ‘A Rake’s Progress’ (1961–3) and other early etchings, there is an important companion show at Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert in Mayfair. Hockney drew straight on to the etching plates, giving his impressions a quick-fire immediacy. His black lines scatter like iron filings pulled by magnets. ‘The Hypnotist’ (1963) is wickedly sinister.

There is more of this hypnotism in the final room at Tate, a gallery of Hockney’s iPad drawings on live screens. This is the conjurer unmasked: we see how the trick is done, the sketch animated line by line as he draws with a finger on the screen. The thumbnails appear and disappear: shoes by a bed, cigarettes and an ashtray, a can of Brasso, two bottles — ‘We are in Baden Baden enjoying the magic waters.’ You lose track of how long you’ve been standing there.

This is a nakedly bombastic show: colour, heat and sex, both tender and obscene.

Hockney gives you homesick nostalgia for Bridlington woods and the whizz-bang technology of iPads and video installations. His art is one of restless reinvention, of joy in new possibilities — acrylic paints, the Polaroid camera, the fax machine, high-def digital video, the scribble on the iPhone screen — of diving into the water and coming out new.

Comments