The United Nations Security Council has major responsibility in its job description: to maintain international peace and security. It is spelled out in Article 24 of the U.N. Charter, a tall task in normal circumstances but one that nonetheless underscores the core of the council’s very existence. Without it, the Security Council might as well be simply another distinguished debating society – a place where interesting, intellectually stimulating conversation occurs but where people leave without finding much consensus.

On the subject of Syria, the top U.N. body has been anything but distinguished. Nor is there serious debate going on in the room. Conversations on how to stem the violence perpetrated by the Assad regime, how to introduce some accountability for the war crimes that all parties have inflicted on the Syrian population, and how to speed up the delivery of humanitarian aid to areas that have been besieged for years have a habit of deteriorating into screaming matches and childish invective. At the heart of the dispute is the United States and Russia, two veto-wielding permanent members who can stymie one another’s initiatives and resolutions by casting a simple “no” vote. When all is said and done, the chamber adjourns with nothing to show for a day’s work except bad feelings – feelings that inevitably pile up and fester more grievances.

These dynamics reached a boiling point earlier this week, when the Security Council held an emergency session on the chemical weapons attack in the Damascus suburb of Douma, an attack that killed around 50 civilians. The topic on the agenda: passing a resolution that would ascribe blame. Coming together in order to determine who gassed dozens of civilians should not be a particular controversial endeavour. And yet watching the deliberations, one would think that the delegations around the table were going through a painful root canal. Moscow blocked Washington’s resolution to establish a joint inquiry to assign culpability, calling it a scheme imposed by the west to embarrass the Kremlin and lay the groundwork for missile strikes against Assad’s regime.

U.S. Ambassador Nikki Haley returned the favor, shooting down two of Russia’s resolutions that would essentially slow-walk an inquiry and leave the final judgment to the Security Council, which of course the Russians could veto depending on the result. Haley wasn’t pleased with Moscow’s behaviour. “You know, my parents always said you should always see the good in everyone,” she remarked after the vote. “And you should always see the good in everything. So I’ve been trying to figure out what the good is with Russia.”

At the same moment diplomats in New York were acting undiplomatic, the war in Syria was continuing apace – a war that will only end in Assad’s mind until every inch of Syrian territory is back under his government’s control.

There are a lot on unanswered questions on Syria. Will there be more chemical weapons attacks when the Syrian government and its allies begin large-scale military operations in rebel-held Idlib, a province jam-packed with refugees? Will President Donald Trump answer Assad’s use of chemical weapons by retaliating with more cruise missiles? Is U.N. special envoy Staffan De Mistura wasting his time, or does he still believe he can scrounge up some kind of negotiated transitional process? Has Syria poisoned the well of the U.S.-Russia relationship, or can it still be pulled out of the gutter?

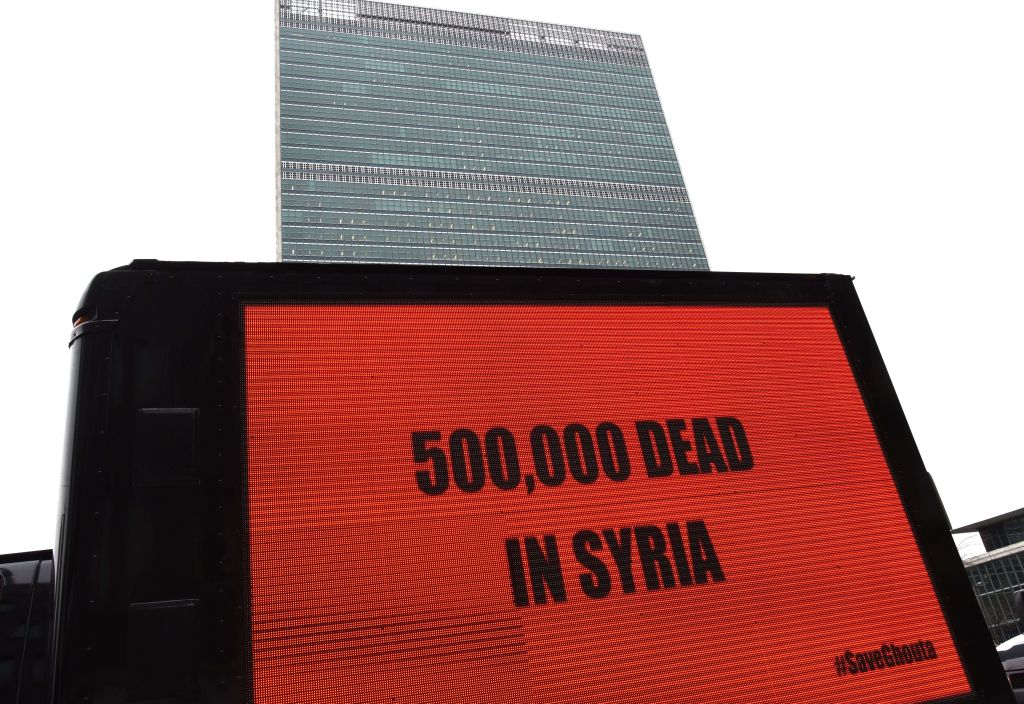

One thing, however, is certain: on Syria, the Security Council has been beyond useless. We have long gotten past the point in time when this historical chamber could do much to solve or even stabilise this most unmerciful of wars. The latest embarrassment was just further confirmation that the entire U.N. system has been ground to a halt.

Comments