Lloyd Evans talks to Michael Attenborough, whose star at the Almeida is the theatre itself

The back office of the Almeida Theatre in Islington could do with a major refit. Dowdy, open-plan and scattered with Free-cycled furniture, it looks like the chill-out room of a student bar or the therapy suite of some underfunded weight-watch clinic. The tin chairs are arranged around elderly coffee-tables. The walls have been painted with the ramshackle expediency of a squat — a blue stretch here, some scarlet columns there, a few purpley flourishes. Beneath the roof eaves a beer gut of damp and crumbly brickwork bulges outwards precariously. I’d give it three months, maybe six, before it collapses. A grungy sofa receives my weight with an audible sigh, as if it’s been sat on once too often.

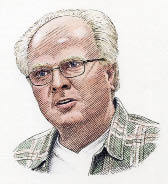

I’m greeted by the theatre’s artistic director, Michael Attenborough, a bustling, compact little man of about 60. He has the same broad, genial face as his father, the film director Lord Attenborough, but he’s less sleek-looking with shaggy wisps of hair swept backwards from the shiny dome of his forehead. We shake hands and his intense eyes scan me briefly. He ushers me past a side-office, where an all-girl team of fund-raisers are busy bashing the phones, and into a boardroom which is fractionally less frumpy than its neighbour. Clearly the creative focus here is on the work rather than the habitat.

He launches into a rapid-fire overview of his forthcoming production Through a Glass Darkly, an adaptation of Ingmar Bergman’s 1961 film. ‘Bergman was implacably opposed to people doing stage adaptations of his films. This is the only one he gave permission for during his lifetime. It’s very tight, claustrophobic almost, only four characters — Bergman called it “a chamber film” — and it lends itself very well to the unities of the theatre.’ Attenborough and his writer Jenny Worton have changed the ending. ‘Very slightly,’ he tells me, ‘but interestingly we learnt that Bergman didn’t like his own ending. And if he were alive today, he’d make changes himself. Bergman experts aren’t going to look at it and throw their hands up in horror.’

We move to the problems of managing a small theatre with a world-class reputation. How does he choose his programme? ‘Oh, well, I go out into the garden and I say, “Mmm that plant looks good, that plant looks good, that plant looks good. Gosh, I’ve got a nice little bouquet.”’ This whimsical burst of Bo Peepery makes me blink slightly. It seems so at odds with his disciplined and rigorous manner. ‘The real point is this,’ he says, reverting to his natural demeanour. ‘We don’t have a monopoly on ideas. Projects originate in multifarious ways. A director brings me an idea or an actor comes in and says, “I’ve always wanted to do this script.” Or maybe Neil LaBute sends me a new play, so I read it and if I love it I go, “Yup.” Final full stop. Turn the last page, we’ll do that play. And it’s great. That’s the Almeida. We’re maverick, unpredictable, catholic, eclectic. One moment it’s Shakespeare, next a musical, then a new play or a foreign classic. There’s only one demand on the Almeida. Take risks and be exciting.’

He mentions the Almeida a lot. Never this theatre, my theatre, our theatre. The Almeida. It could be an obsession, or shrewd marketing, or just the innocent pleasure he takes in overseeing the shop. Funds are a constant worry and he has to balance the competing demands of private donors, the Arts Council and his long-term sponsors, Coutts & Co. ‘If I had to economise tomorrow, the post I would shed is assistant director. So you might ask why are we spending money unnecessarily. We do six shows a year and six new assistants get a chance to start. It’s a training initiative.’ He seems to regard himself as a public servant first and an impresario second.

We discuss the playhouse that most theatre-goers regard as the Almeida’s chief rival, the Donmar. ‘We’re nearest cousins,’ says Attenborough, twice, before outlining an approach which is subtly different from Michael Grandage’s. ‘Because he [Grandage] was an actor, he’s a hugely empathetic director for actors. It’s no accident that stars have very much led the way. I don’t have a problem with that.’ He is referring to last year’s Donmar season in the West End featuring Kenneth Branagh, Jude Law, Derek Jacobi and Judi Dench.

When Attenborough took control of the Almeida, he asked his predecessors, Jonathan Kent and Ian McDiarmid, if there was anything they would do differently. ‘Hire fewer stars,’ they told him. Attenborough endorses this. ‘Stars fill your theatre, give you great performances and raise your profile but they can create the sense of “Who’s on?” rather than “What’s on?” For me the star is the Almeida. Our supporters might look at the programme and say, “I’m not sure I want to see a play about the plight of women in the Congo but I’ll go because I trust the Almeida to do it to a superlative standard.”’

A steady flow of Attenborough productions has transferred to the West End although he admits these migrations haven’t produced ‘shedloads of dosh’. And the westward trajectory isn’t an abiding obsession. At one point he refers to it merely as ‘a second step’ and suggests that the real story of British theatre lies with the outlying venues that feed the West End, ‘the Royal Court, the National, the Young Vic. And the Almeida.’

He seems to have developed quite a distaste for Shaftesbury Avenue. ‘The problem isn’t the theatres themselves, although many of them need a massive overhaul; the problem is that it’s a completely loathsome place to go. You walk through this Hieronymus Bosch environment, struggle to your seat, have horrible wine, your knees pressed against the row in front of you, a spring up your arse, and the tickets are overpriced. Sixty pounds.’ He pauses. ‘The Almeida’s top ticket is half that.’

He doesn’t blame the producers. ‘The noise, the filth, the polluted, litter-strewn streets, these things aren’t their responsibility. They’re just trying to make ends meet.’ He moves to more congenial terrain. ‘At the National it’s completely different. You slide into the underground car park, walk up in a civilised way, get perfectly decent food and drink, see a play, collect your car and drive home.’ Another pause. ‘By the way, you can park outside the Almeida.’

Perhaps that explains why he runs his theatre as he does. The chaotic, tumbledown interior helps generate a steady stream of dramatic treasures. It’s not the Donmar he’s trying to emulate. It’s the National.

Through a Glass Darkly runs at the Almeida until 31 July.

Comments