‘Some day we shall no longer need pictures: we shall just be happy.’ — Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter, 1966

Who says Germans have no sense of humour? OK, so their writers tend to be a pretty gloomy bunch — but like loads of other German artists, from Otto Dix to Georg Baselitz, Sigmar Polke’s paintings are illuminated by a dry, mordant wit. It’s encapsulated in an early doodle called ‘Mona Lisa’ (1963), which hangs near the entrance to this hugely enjoyable retrospective — the first comprehensive survey of his eclectic, eccentric work. ‘Original value $1,000,000,’ reads the handwritten caption. ‘Now only 99c, including frame.’ That Polke’s pictures now sell for many millions (with or without frames) adds another layer of meaning to this student jape.

Polke’s work isn’t all fun and games, but he never took himself too seriously, despite the hardships of his early life. Born in 1941, into the Third Reich, he was expelled from Silesia in 1945 when the German province was annexed by Poland. His family fled again in 1953, from East Germany to West Germany. This double displacement was traumatic, but it did wonders for his painting. Polke never seemed stuck in a particular genre. This exhibition feels like a group show by half a dozen different artists. Swastikas cast occasional shadows across his paintings, but although he’s never frivolous about the Nazis, neither is there any hand-wringing. His perspective is that of a wry observer, an outsider looking in. One of his most famous pictures is called ‘Polke as Astronaut’ (1968). He’s like a playful visitor from another planet. There’s something supremely dispassionate about his art.

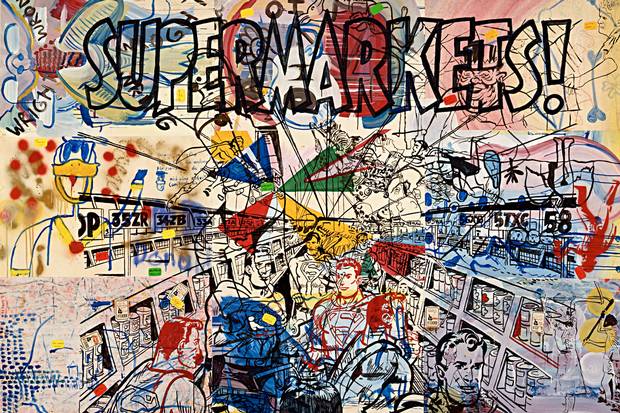

After a short spell as an apprentice glass painter (leaving him with an enduring interest in transparency and distortion), Polke trained at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, a powerhouse of postwar German art. Capitalist Realism was the title that Polke and his fellow students (including Gerhard Richter) gave to their ensemble shows. This was another splendid joke. While the German ‘Democratic’ Republic promoted social realist depictions of happy workers, Polke poked fun at western commerce and the pious dogma of modern art. An abstract daub is labelled ‘Modern Art’, like a paint-by-numbers picture in a high school primer. An African sculpture is superimposed upon a piece of cheap fabric, decorated with teddy bears and bunny rabbits. The instruction on a minimalist painting reads, ‘Higher Beings are commanded to paint the upper-right corner black!’ (1969). Yet just as you start to think the whole show will be a series of artistic in-jokes, you’re confronted with artworks of great serenity and beauty. Turns out Polke was just playing with us. Seems he really was sincere about modern art.

His mature work took abstraction to a new level. At the 1986 Venice Biennale, he daubed the German pavilion with a special pigment that changed colour depending on temperature and humidity. He worked with dye from snails, and dust from meteorites. He played with Rorschach patterns. He painted on bubble wrap. He hung out at Ayers Rock.The last few rooms of this one-man show could scarcely be more different from the first. Polke’s imagery becomes more and more disturbing: pictures filched from porn mags, Nazi textbooks, the tabloid press… Yet even at his most iconoclastic, he doesn’t simply set out to shock. His dot painting of Lee Harvey Oswald mimics the blurred perspective of cheap newsprint. A trite newspaper slogan is reproduced back to front. A homemade lens obscures the image beneath the glass, rather than revealing it. These paintings seem to sum up the information overload of modern life.

And then you reach the end and suddenly all is calm and quiet. The last room features four beautiful abstract paintings, like depictions of distant galaxies. They feel as if they should be in a cathedral, which is fitting, since Polke’s last major work was a series of stained-glass windows for a church in Zurich, a return to the art form of his youth. When you see these windows in Zurich, the effect is mesmeric. Here at Tate Modern, you have to make do with a short film — but even on the small screen, they’re stunning. I can’t remember when I last left a gallery feeling so reinvigorated and refreshed.

In fact, my only quibble with this thrilling show is its title. Polke straddled many styles, but none of them seem like alibis. What gives his art such power, and makes it so exciting, is that throughout his many incarnations, he was never putting on an act.

Comments