Who knows what Rachel Reeves reads in bed. Perhaps she dips into her own debut book, The Women Who Made Modern Economics (2023), and dreams of those carefree pre-government days when serious people, Mark Carney for one, thought she might make a decent Chancellor. But if she’s also burning midnight oil over drafts of her Autumn Statement, I hope her boxes are packed with granular data on the state of the UK job market.

September normally sees a recruitment surge, but not this year. A summary of recent stats in IFA Magazine shows vacancies down by 119,000 from a year ago and entry-level graduate jobs down by as much as a third, as diminished hiring focuses on ‘skills-based’ selection rather than useless degrees. The number of ‘payrolled employees’ fell by 142,000 in the year to July, while small business lobby groups also report jobs lost and fewer vacancies as entrepreneurs await the next Reeves sting. Needless to add, public sector employment is a rare graph-line pointing upwards, by 17,000 year-on-year.

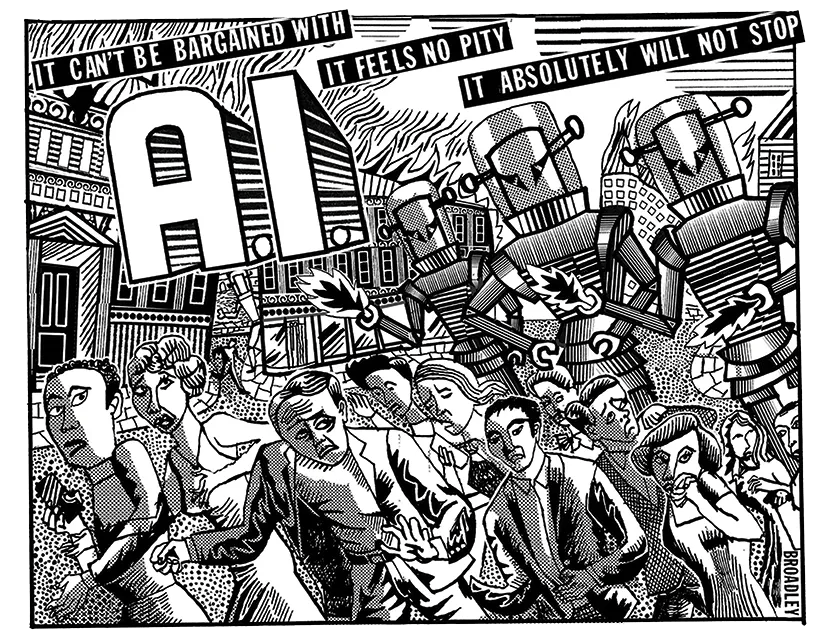

Tech gurus tell us we’re at the start of a wave of job destruction as human tasks are taken over by artificial intelligence – from which corresponding productivity gains are as yet wholly uncertain. AI may also be a factor in this season’s job market cooling, particularly at graduate entry level, but at least the overall trend has the side-effect of reducing inflationary wage pressure.

The Chancellor will doubtless remind us that the total UK workforce of around 37 million is close to its record high, though I doubt she’ll admit it’s continuously boosted by immigration; and though our unemployment rate is at a four-year peak of 4.8 per cent, she’ll say, it’s still close to the G7 average. But she probably won’t mention the 9.1 million working-age people who are ‘economically inactive’ – or state the obvious conclusion from current evidence, which is that jobs are increasingly at risk and good ones harder to find.

Meanwhile, what else should she be reading on the pillow? I suggest a file of post-Budget cuttings from October last year to remind her how many pundits correctly predicted the dire outcome of her tax raid on businesses, particularly smaller ones that are the true engines of growth and jobs. This time, she’s set to attack wealth in property and pensions, despite the exodus that will provoke and the deterrent effect on investment. But the furore that follows will at least give cover for less obvious moves: the bold Chancellor she once might have become would use it to reverse the entirety of last year’s benighted anti-business package.

Disorderly adjustment

The likelihood of any market crash must bear some relation to the frequency with which ‘crash’ and its synonyms have recently appeared in headlines, broadcasts and speeches. Right now, that word chart should certainly be giving investors pause for thought, if not yet telling them to head into the woods with a stock of canned food and whisky. The prime cause for concern is the overvaluation of US stocks associated with AI (which turns out to be the theme of this week’s column) and the fear that current riders of the wave such as Nvidia, Oracle and Palantir will be overtaken by other companies, as yet unknown, which will reap the real rewards of the next tech era.

In short, there’s an AI bubble out there and the big question (the late 1990s dotcom bubble providing a vivid precedent) is not whether it will burst, but when. Jamie Dimon, one of the world’s wisest bankers as chief executive of JPMorgan Chase, predicts a six-months-to-two-years timeframe. The Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey warns that ‘asset valuations could now be at odds with the uncertain economic and geopolitical outlook, leaving markets susceptible to a disorderly adjustment’. That last phrase is almost as circumlocutory as the Duke of York’s use of ‘unbecoming’ in relation to Jeffrey Epstein. But the warning is clear enough: at the very least, it’s time to take profits on stocks that have rocketed.

Crypto winner

One mini-crash has already kicked off – in the crypto arena, where bitcoin and other tokens have plunged in apparent response to Donald Trump’s threat of 100 per cent tariffs on imports from China, itself a reaction to Chinese curbs on exports of rare-earth elements to US tech manufacturers. If that shows a welcome outburst of worldly attention on the part of normally spaced-out cryptonauts, we should also salute the Hong Kong trader Garrett Jin, who reportedly reaped a $150 million profit by taking a huge short position in bitcoin minutes before Trump sent the price tumbling. Much as the President loves to be seen with winners, I doubt he’ll invite Jin to the White House.

The human touch

The Chancellor’s book on female economists was allegedly assisted by Wikipedia rather than by the then novelty of AI chatbots, but nowadays I’m frequently asked whether my own writing is in danger of being supplanted by AI. Not yet, I reply, because I don’t think it does jokes or restaurant tips; so far, I find it more of an aid than a threat. For example, when I ask Google’s AI function ‘Could AI replace columnists?’, it offers this succinct answer: ‘AI can’t fully replace magazine columnists because it lacks the human creativity, critical analysis and personal experience needed for nuanced commentary… However, AI can be a valuable tool for automating research… freeing up columnists to focus on more strategic and creative aspects of their work.’

And lunch, it might have added, if it had the human touch. Speaking of which, stars for best service at this year’s Spectator Economic Innovator Awards regional lunches go to Steven at Gleneagles Townhouse in Edinburgh and Luke at Hotel du Vin in Newcastle. The food was also first-class; as indeed were the sparkling variety of entrepreneur finalists, despite all that the Chancellor has thrown in their path.

Comments