The question ‘Was Shakespeare gay?’ is not very rational. It might be a little like asking ‘Was Shakespeare a Tory?’. Some of his scenarios might coincide with later developments – Jaques trying to pick up Ganymede in As You Like It (gay), or Ulysses’s speech on degree in Troilus and Cressida (Tory). But the historical conditions are not there. No doubt there have been people keen on same-sex relations since the dawn of time. But the possibilities of a social identity embedded in the word ‘gay’ didn’t exist in the 16th century, nor the medical diagnosis from which the word ‘homosexual’ arose. Nor will ‘sodomite’ do. That describes some very different sexual tastes and practices through history.

Will Tosh uses the word ‘queer’, which will seem distasteful to many survivors of queer-bashing now. I think, too, that it has been rendered useless as a descriptive term by the recent tendency of any straight couple under 30 who have ever shared a bottle of nail varnish so to describe themselves. Probably what we can conclude is that, for early modern society, these were acts and not fundamental states of being – sins and temptations that people might be more or less prone to, and more or less given to indulging. Somewhere in that ‘more or less’, we might guess, lay Shakespeare. But we don’t know, and we don’t have a word for it.

Still, we know what we are talking about: same-sex desire. There is a fair amount of it in Shakespeare’s works; but there is no real suggestion, in the biographical traces, that he had a weakness in that direction. There are some bitchy comments by contemporaries about him, from Robert Greene’s ‘upstart crow’ to Ben Jonson saying he had ‘small Latin and less Greek’. One of them, surely, would have made a cutting remark about a fondness for boys. For something resembling evidence, we have to look to the plays and poems.

Tosh has written a well-informed book that places these expressions of desire in two contexts. The first is the historical one – of where same-sex society might have flourished or been tolerated. The second is the literary one – of the points in the late 16th century when literary fashion encouraged expressions of same-sex feeling, or where conventions of representation might have permitted a more explicit performance of the illicit practice than we understand now, or than would have been permitted offstage then.

The moments in the plays when it arises have been much dwelt on by recent writers. Some of them seem to me pretty unconvincing, and Tosh, too, appears to overstress intense male friendships – such Romeo and Mercutio’s – as containing same-sex desire. The Renaissance was keen on intimate friendship as extolled by Cicero. What it genuinely was, was friendship. Those treatises weren’t written in bad faith, and the devotion we see in The Two Gentlemen of Verona isn’t a romantic passion. (The devoted friendship between heterosexual men must now, in reality, be the most neglected form of love in existence.)

But there are signs of same-sex desire, some classical, when Thersites castigates Achilles and Patroclus in Troilus and Cressida; some more original, in Othello, when Iago queasily invents his own ravishment by Cassio when they were sharing a bed. When Jaques opens the fourth act of As You Like It by saying to Ganymede ‘I prithee, pretty youth, let me be better acquainted with thee,’ we certainly glimpse a morose and unsociable queen trying out a supremely ineffective pick-up line. It might be observed, too, that relationships in some plays in modern times have been given a strongly homo-erotic flavour without violating the existing psychology. The rivalry and passion between Coriolanus and Aufidius, for instance, works very well onstage if there is a gleam of sexual tension there.

It may have been the case that the homoerotic frisson was heightened at the time, too, by the fact that the love scenes between heroes and heroines, often disguised as boys for the purposes of the plot, were in fact a man kissing a boy onstage. This becomes an acute point in Twelfth Night and As You Like It, with a marriage ceremony performed between two actors, both in male dress. Tosh is good at unearthing works by contemporaries that take Shakespeare’s inventions in this line further. I wish he’d mentioned Jonson’s extraordinary play Epicoene, in which an old grump is persuaded to marry a silent woman who turns out to be ferociously voluble. It’s only at the curtain that the woman’s wig is whipped off, and the audience informed that they haven’t been watching a boy playing a woman; the main character has been cheated into marrying a boy disguised as a woman.

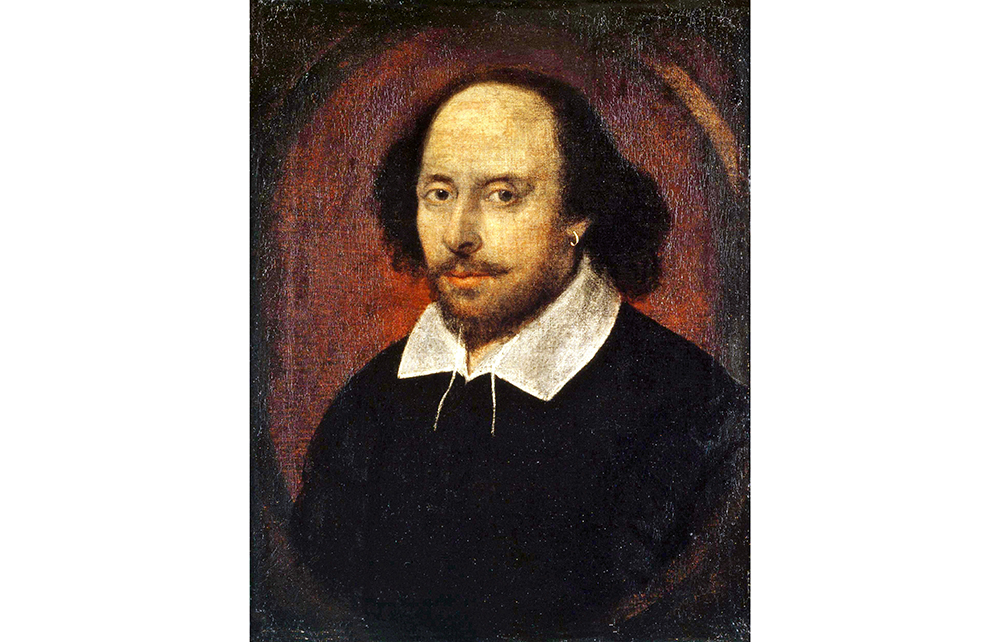

That the sonnets were written by

a man who had overpowering feelings

for another man is undeniable

Some of this was the product of literary fashion. Tosh does a good job of explaining how the sex-disguise comedy relates to mythical dramas such as John Lyly’s Galatea. The notably lascivious descriptions of Adonis’s charms, rather than Venus’s, in the best-loved of Shakespeare’s narrative poems, are usefully surrounded by a bunch of other pretty-boy Ovidian mini-epics.

Where fashion fails is when we come to exhibit A in the was-Shakespeare-gay case: the sonnets. They are resolutely unlike other erotic sonnet cycles of the time – no classical personae, such as in Richard Barnfield’s smutty boy-on-boy ‘The Affectionate Shepherd’. (Barnfield is the one writer who seems to have paid a price for his tendencies. Tosh makes a convincing case that he was dropped sharply by patrons and disinherited by his wealthy father for this reason.) Shakespeare’s sonnets aren’t conventional exercises, like Venus and Adonis. The only explanation for them appears to be that they are something like statements from personal experience, like Donne’s love poems. That experience is irrecoverable; but the impression that these were written by a man who had overpowering feelings for another man is impossible to deny.

This is an interesting book, with plenty of useful references to works by Shakespeare’s contemporaries, both well known (Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II) and now forgotten (Thomas Peend’s Hermaphroditus and Salmacis). But I do think that the case is strongly inflected by our present-day concerns, and I remain unconvinced that early modern playwrights have anything to contribute to the current trans debate. It’s true that characters frequently disguise themselves as the opposite sex. But they also disguise themselves as walls (A Midsummer Night’s Dream) and occasionally turn into trees, clouds or showers of gold. Shakespeare and his contemporaries believed a lot of odd things. They thought that bears were born as inchoate blobs which their mothers had to lick into bear-shape, for instance. Shakespeare clearly thought that Bohemia had a coastline, that the ancient Romans had clocks and billiard tables, and that identical twins didn’t have to be the same sex.

Even so, I don’t see any sign that he, or anyone at that time, seriously supposed that someone born a man could really be a woman, or become one. It might be a way of talking – as when Lady Macbeth asks to shed her womanly characteristics to become more ruthless. Or it might simply be a fantastic event, like the gods descending. None of this has anything to do with today’s bundle labelled LGBTQIA+, compared to same-sex activity, and it shows a certain historical solipsism to flatten out the past to fit better with our interests. What one wants from a book about Shakespeare is not an explanation about how same-sex desire in the 1590s was much like ours on a Friday night down the Royal Vauxhall Tavern. Rather, one wants to be shown how very strange and curiously distinct it might have been.

Nevertheless, this is an engaging, enthusiastic and informative book about one facet, long denied or ignored, of the most teasing and various of all great writers.

Comments