‘Whether I am a trembling creature or whether I have the right…’ The much quoted words of Rodion Raskolnikov, the protagonist of Crime and Punishment, encapsulate the novel’s main question. Fyodor Dostoevsky first pitched the idea of ‘the psychological account of a crime’ to a publisher in 1865. Three decades earlier, a real-life murderer, Pierre François Lacenaire, waiting for his execution in a French prison, wrote: ‘Only I can decide whether I have done wrong or right to society.’ As Kevin Birmingham shows in his new book, this is but one detail of Lacenaire’s story mirrored in Dostoevsky’s masterpiece; moreover, Dostoevsky’s reflections on the case influenced the way he understood the nature of evil.

The Sinner and the Saint works on several levels: as a historical study, a work of literary criticism and, gratifyingly, a double thriller. Chapters on Dostoevsky and Lacenaire alternate, the storylines running parallel to one another, each towards its own climax. Dostoevsky loses his parents early and renounces his share in his father’s estate to become a writer. Lacenaire is abandoned by his impoverished family and dabbles in poetry. Dostoevsky joins a radical group to read and discuss works banned by censorship; soon the conspirators are denounced and imprisoned. Lacenaire goes to prison for stealing a horse and carriage, and decides that his place is among the outlaws. Dostoevsky and his comrades are sentenced to death. As they stand blindfolded before the firing squad, the mock execution is stopped. His sentence commuted to penal servitude, in Siberia Dostoevsky talks to other inmates and records his observations in a secret diary. Back in Paris, Lacenaire, now a proponent of ‘ferocious materialism’, kills two people. His trial causes a sensation. He enjoys his celebrity status during the proceedings, writes a memoir and dies on the guillotine.

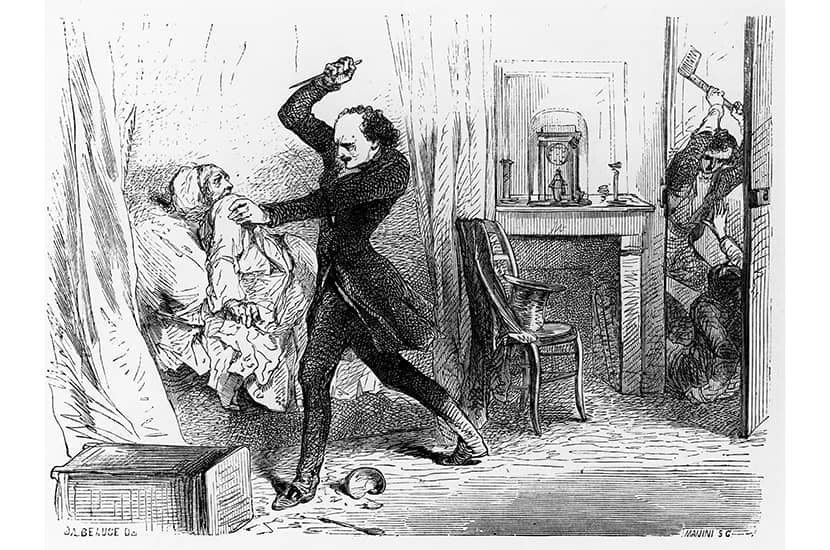

‘One must study so many murders to write just one murder story effectively,’ said Dostoevsky

After ten years in exile, in 1859 Dostoevsky returns to St Petersburg to rejoin literary life. It is there that he learns of the affair that once shook France. He co-translates an account of the Lacenaire case and publishes it in his magazine. ‘One must study so many murders to write just one murder story effectively’; so Dostoevsky adds Lacenaire to his growing collection of criminals (‘He was handsome. He was contemptuous of everything. He was afraid of nothing,’ Birmingham writes of one of the specimens), eventually channelling it all into Raskolnikov.

The key motifs underpinning both these narrative strands are violence and money. ‘Poverty is not a vice!’ was a refrain in Dostoevsky’s life; he constantly begged editors for advances and dreaded the debt prison. Lacenaire, too, tried journalism, but was only paid five francs instead of the promised 25. ‘It’s an oligarchy,’ Dostoevsky complained about publishing sharks as he signed away an unwritten novel for a pittance and embraced gambling. Birmingham compares roulette to writing:

You play every spin, you turn every page until you have lost and borrowed and pawned everything you own down to your last paragraph. Dostoevsky’s closing sentence was his silver watch.

The crimes at the centre of the book are both ostensibly about money, but the real motives lie deeper. Lacenaire, by his own admission, murdered for no better reason than having the desire and the means: ‘I kill a man as I drink a glass of wine.’ He didn’t, however, neglect to use the spoils. Raskolnikov, by contrast, leaves the pawnbroker’s purse unopened; later, confessing the murder, he struggles to explain what exactly drove him to it. As Birmingham dissects the novel, he recounts large parts of it in the dramatic present: ‘The blade splits the top of her forehead like wood, and she falls.’

To contextualise Dostoevsky, Birmingham immerses the reader in Russian history, which is counterpointed by the French material. While iron shackles are the norm for Russian convicts, in French prisons they are an ‘extraordinary measure’; in France, people exchange cash for bank bills, while Russians issue promissory notes, getting used to new debt relationships. Half a century after Napoleon’s defeat, questions of reason, freedom and power acquire new philosophical dimensions across Europe, thanks to a proliferation of Hegelian ideas. ‘I wanted to become a Napoleon,’ Raskolnikov says, trying and failing to justify his actions. Birmingham subjects Crime and Punishment, as well as Dostoevsky’s copious notes, to a very close reading, before concluding: ‘Raskolnikov doesn’t kill for an idea. Raskolnikov kills for nothing.’

Writing about one of Russia’s greatest authors is bound to be difficult: the sheer weight of sources must be overwhelming. Birmingham manages to shift historical layers with seeming ease, combining scholarly rigour with liveliness, historical breadth with lightness. Sinners and saints, real and fictional, are cast in a sharp new light; big themes come alive in a kaleidoscope of little things. A frock coat for a condemned man; a drawing emerging from lines of text in a notebook; a moment of bliss before an epileptic fit — the devil, as always, is in the detail.

Comments