By the late 1980s, the war against pornography was lost. Feminists, as well as Christian moralists, mainly in the UK and US, had been raging against the industry since the early 1970s. In 1980, the American feminist author Robin Morgan coined the phrase: ‘Pornography is the theory, rape is the practice.’

In 1983, alongside the legal scholar and feminist author Catherine MacKinnon, Andrea Dworkin came up with the Dworkin-MacKinnon Anti-Pornography Civil Rights Ordinance, which would have granted those directly harmed by pornography a right to civil recourse by enabling victims to sue both the producers and the distributors of porn. The inspiration for this was Linda Lovelace, the star of Deep Throat, who said that she had been forced into making the film and raped during its production. The ordinance proved generally unpopular, with critics claiming ‘free speech’ violations, and eventually died a death.

Today, the porn trade drives not only technology, but also culture, politics, sexual behaviour and desires. Pornocracy, by Jo Bartosch and Robert Jessel, explores both how it all happened and what the consequences are – for women, men, children and humanity in general.

Chapters such as ‘Not your Grandad’s Porn’, and ‘How Porn Changed our Brains’ are packed with original material and follow the route from the early days of feminists protesting against top-shelf magazines on the basis of sexual objectification, to the violent, sadistic material which prepares men, the authors argue, to access child abuse imagery and even necrophilia-based categories.

How does Big Porn get away with it? How did it come to be part of the fabric of popular culture and human behaviour? It’s important to understand that what turns pornographers on is not sex but money. Unsurprisingly, in a book covering such a huge topic, there are sweeping statements, some of which I would question. For example, in discussing how a disproportionately high number of child sexual abuse survivors are attracted to an industry built on abuse, the authors quote the psychotherapist S.E. McCollum, who sees it as a survival tactic because they become acclimatised to better tolerate the abuse.

Nevertheless, Pornocracy offers a gripping account of how this dangerous industry has risen to such heights that it is now determining our cultural norms. One chapter examines the Gisèle Pelicot case through the lens of its digital dimension: in anonymous online chat rooms, videos within phones and on laptops broadcast to many men at once. Social networks were another aggravating factor. The chapter is aptly titled ‘The Death of Love’.

Professor Kathleen Richardson is probably the country’s most eminent expert on AI human replicas. She has now distilled her many years of research into the readable yet harrowing Sex Robots: The End of Love.

Can a person buy love? Or sex? No, says Richardson; it is impossible to extract either from a human. Sex robots are founded on the idea that it is possible to have sex outside of a person. Only things and tools can be commercially exchanged, so it can only be done by turning the body into an object. But the body is always part of a person – so you can’t really have a sex doll, only a porn bot.

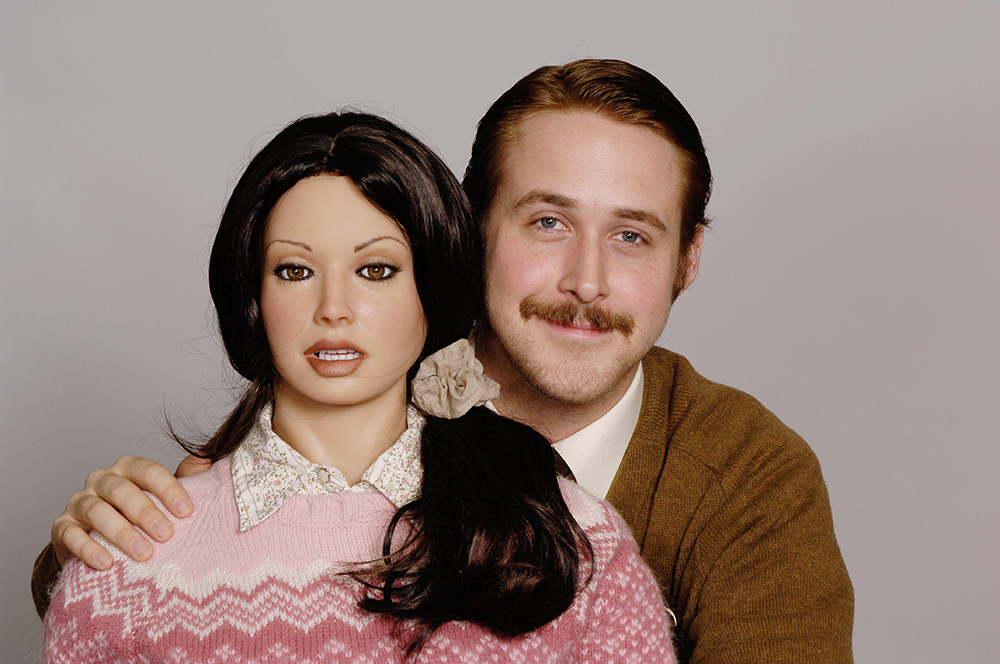

Sex robots have long been familiar within popular culture and feature in the films The Stepford Wives (1975) and Ex Machina (2014). However, Lars and the Real Girl (2007) did more than either to normalise the use of inanimate objects as faux girlfriends for men – and to provoke sympathy and empathy for their consumers. It is based on the story of Lars Lindstrom (played by Ryan Gosling), an implicitly autistic character who buys a hyper-realistic sex doll and passes it off as his girlfriend to family and colleagues – all of whom go along with his fantasy that the doll is a real woman. The film gifted a large commercial boost to RealDoll, a US-based company that, from the mid-1990s, led the way in making life-sized, hyper realistic dolls for men.

Richardson studied at MIT where the idea of robots and AI entities as ‘relational others’ began. She went there in the mid-2000s to research the phenomenon as part of her doctoral fieldwork in social anthropology. As she explains in her introduction, early in the decade she knew that anthropomorphic robots were being made and wrongly assumed this was to lighten workloads to enable people to be more free. But in fact the robots were designed to be ‘socially interactive’ and ‘companions’. This was so shocking to her that she began to investigate the potentially detrimental consequences.

The first three chapters tell the story of the problem – pornography, prostitution, child sexual abuse, all familiar themes – but the chapter that really struck me is titled ‘Love: I-You Attachment’, in which she focuses on Martin Buber’s work on attachment theory.

Bartosch, Jessel and Richardson have achieved the near impossible: making books about grotesque topics that are both readable and inspiring.

Comments