I once interviewed the late Enoch Powell for this magazine (the article never appeared, for reasons I forget). One thing he said on that occasion stuck with me. He remarked that loyalty to one’s country should be unconditional. I asked him what he thought people should do if their country were taken over by a criminal regime. After a short pause Powell replied that some people were luckier than others. I failed to press him further on this point, but it struck me as an unsatisfactory answer, and it still does.

Jonathan Freedland has written a very good book on precisely such unlucky people: German patriots who hated Hitler and everything he stood for. Some came to this view earlier than others, but all of them felt that resisting the government of their own country was the right thing to do.

No one could trust anyone. There was an expression for always looking over your shoulder – ‘the Berlin gaze’

In some respects, resisters in countries occupied by the Germans had it easier. They joined the resistance for many different reasons. The humiliation of being subjected to a foreign occupation was one of them. Some were spurred by their religious beliefs or political convictions. Communists were a strong presence in the French resistance and Calvinists in the Dutch. Others felt that hiding Jews, and other acts of resistance, was the only decent thing to do. Still others joined in a spirit of adventure.

Resistance to the Nazis in Germany was more complicated. It was, of course, extremely dangerous, which is why so few people chose to resist or even to criticise the regime in public. In an occupied country, a resister could count on sympathy from people who resented the foreign enemy as much as they did. In Germany, snoops and informers were everywhere. No one could trust anyone. There was an expression for always looking over your shoulder –‘the Berlin gaze’.

Yet some Germans did resist, in a few cases actively, by joining groups or by helping Jews hide and escape. Another act of private dissent was to form intimate circles of like-minded friends to discuss ways to remain decent in a criminal state, and what to do once the tyranny would end.

Freedland’s book focuses on one such group, a social circle revolving around Hanna Solf, the daughter of an industrialist and widow of the former governor of German Samoa. Solf held a kind of salon in her house where former diplomats, intellectual bureaucrats and cosmopolitan aristocrats felt able to speak their minds freely.

Among the most interesting members of the circle was Countess Maria von Maltzan, a veterinarian who continued to risk her life to help Jewish fugitives, one of whom was her lover, whom she married after the war. A scion of an old Prussian noble family, she barely had any money, but she could be very grand. Once, when the Gestapo was about to arrest her, she bluffed her way out in a manner that, in Freedland’s words,

was available only to someone armed with the supreme confidence of the governing classes. If people like Maria von Maltzan acted as if they owned the place, that was because they largely did – and had done so for several centuries.

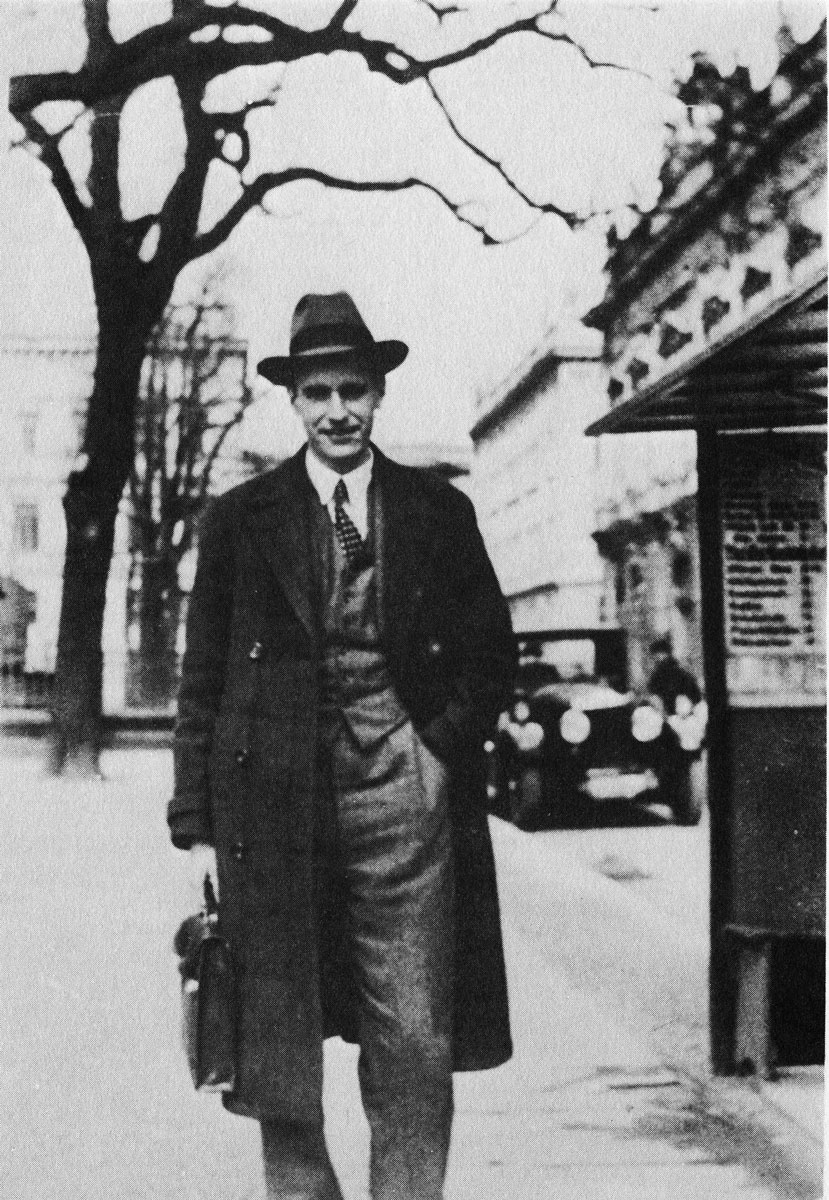

Another friend of Solf was Helmuth James von Moltke. He had his own social gathering of non-conformists, called the Kreisau circle, named after his family estate in Silesia. Many members of these circles had an upper-class background. Most also had international connections. Moltke’s mother was British South African. Otto Kiep, a former diplomat in the Solf circle, was born in Scotland and spent part of his childhood in Glasgow.

Even though, as Freedland points out, quite a few German aristocrats, including one of Kaiser Wilhelm’s sons, became ardent Nazis, Hitler and his satraps loathed the educated German upper class. Like right-wing populists in our own time, they presumed to speak for the common (‘Aryan’) man against the hateful elites. All through the war, Goebbels ranted in his diaries against German toffs attending diplomatic parties.

Not surprisingly, the feeling was entirely mutual. Men like Moltke, or Adam von Trott zu Solz (Balliol College), looked down on the Nazis as vulgar upstarts who had no business to be governing Germany; that, after all, was the rightful role that they themselves had been destined to fulfil. Many of these upper-class men were conservatives, sceptical about democracy and had in some cases been sympathetic to the Nazis in the beginning. But a sense of decency, social pique and the justified fear that Hitler was leading the country to catastrophe turned them against the regime.

For several years during the war prominent members of dissident circles had jobs inside the government. Moltke and Kiep were employed by counter-intelligence (the Abwehr) and Trott was in the Foreign Office. They had hopes of working against the Nazis from within. Kiep even became a member of the Nazi party. Hitler was loathsome to him, but, Kiep said, in the way people often do when faced with rotten leaders: ‘We have to deal with him.’

Once it became clear that there was no way of dealing with Hitler, and that the Nazis were Germany’s ruin, some members of dissident circles began to plot a coup against the Führer. This ended very badly on 20 July 1944 when a bomb laid under the table of Hitler’s HQ in East Prussia failed to kill him, and the plotters, including Trott, were rounded up and hanged from meat hooks in Plötzensee prison.

Freedland’s subjects were socially connected to some of the plotters, but they were not directly involved. This didn’t save them. Hitler’s rage against the men who tried to kill him was so great that he ordered the arrest not just of the perpetrators but their families and many of the people who knew them. They should be ‘hung like slaughtered cattle’, he said.

The Solf circle came to a grisly end after one of their tea parties was infiltrated by a young medical doctor who claimed to sympathise with their views. This odious man, Paul Reckzeh, was in fact a Gestapo informer. He reported on all the subversive opinions freely expressed in Solf’s drawing room. One by one, the members of the circle were arrested and, with few exceptions, beheaded or hanged for ‘defeatism’ and harming the morale of the German people. Reckzeh ended up in East Germany after the war as an informer for the Stasi, in which capacity he even betrayed his own daughter.

Moltke, too, was condemned to death by Roland Freisler, the ‘hanging judge’. Even though he had not been part of the July Plot, he was friendly with the plotters. He was also a very religious Christian, something else the upper-class dissidents often had in common. Freisler demanded to know during Moltke’s show trial whether he wished to obey God or the Führer. Moltke opted without hesitation for the former. He wrote from prison to his wife Freya that this was a cause worth dying for.

Freedland tells the story of Solf and her friends with the vividness of the thrillers he also writes under the name of Sam Bourne. What makes his account of these Germans who refused to conform so important in our own time is that it shows that even the most iniquitous regime doesn’t corrupt everyone. While the likes of Reckzeh do their worst in a criminal state, and most people keep their heads down, there are still those who will stand up for what is right. Freedland’s last sentence is the best riposte to Enoch Powell’s remark to me: ‘When the moment came, they dared to be traitors – not to their country, but to tyranny.’

Comments