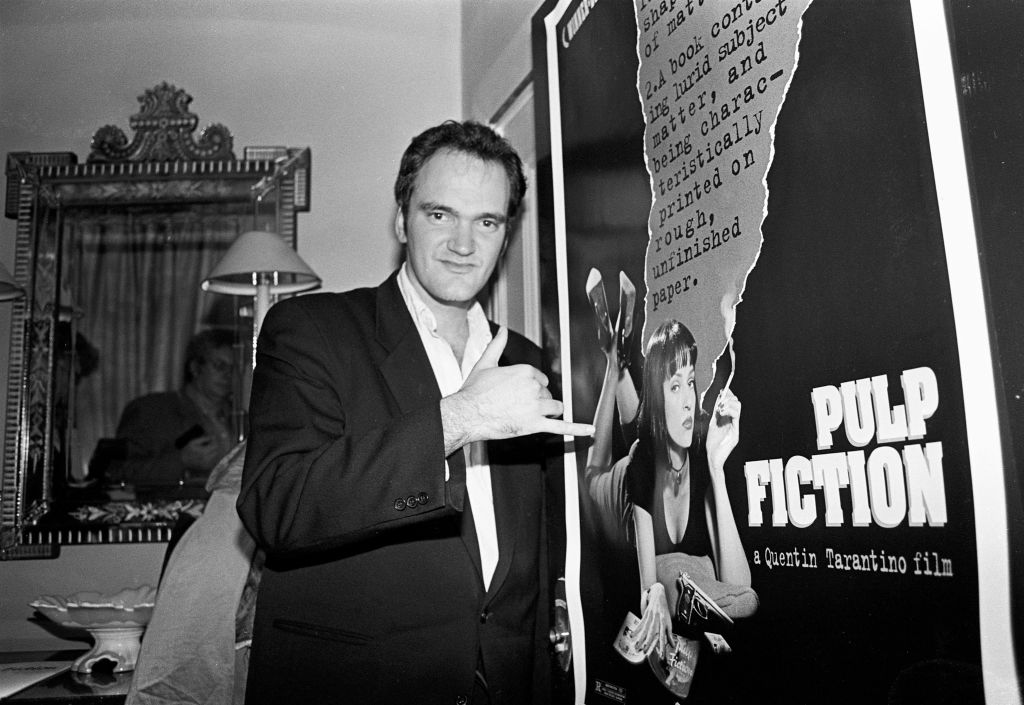

Explaining how she managed to kick her cocaine habit, the singer Fiona Apple recalled ‘one excruciating night’ she spent trapped in Quentin Tarantino’s home cinema with Paul Thomas Anderson listening to the two Hollywood directors brag competitively, and apparently indefatigably, about their professional achievements. ‘Every addict should just get locked in a private movie theatre with QT and PTA on coke, and they’ll never want to do it again,’ she informed the New Yorker some years later. I suppose that’s one accolade the pair will have to agree to share: conversation so unstimulating it undoes all the good effects of hard drugs.

Part of his problem – as the reader of Cinema Speculation quickly notices – is that, as well as being one of the pre-eminent filmmakers of his generation, Tarantino is also an unreconstructed anorak: a self-confessed ‘brash know-it-all film geek’. And as with anoraks, the love he has for his subject is a selfish kind of love. It is a love that doubles- back on itself and becomes part of its own object of fascination. He is more interested in documenting his sensations and observations, and the fact that he had them, than in whether you’re interested in hearing about them.

Most of the films celebrated here strike the reader as grossly eccentric entertainment for a child

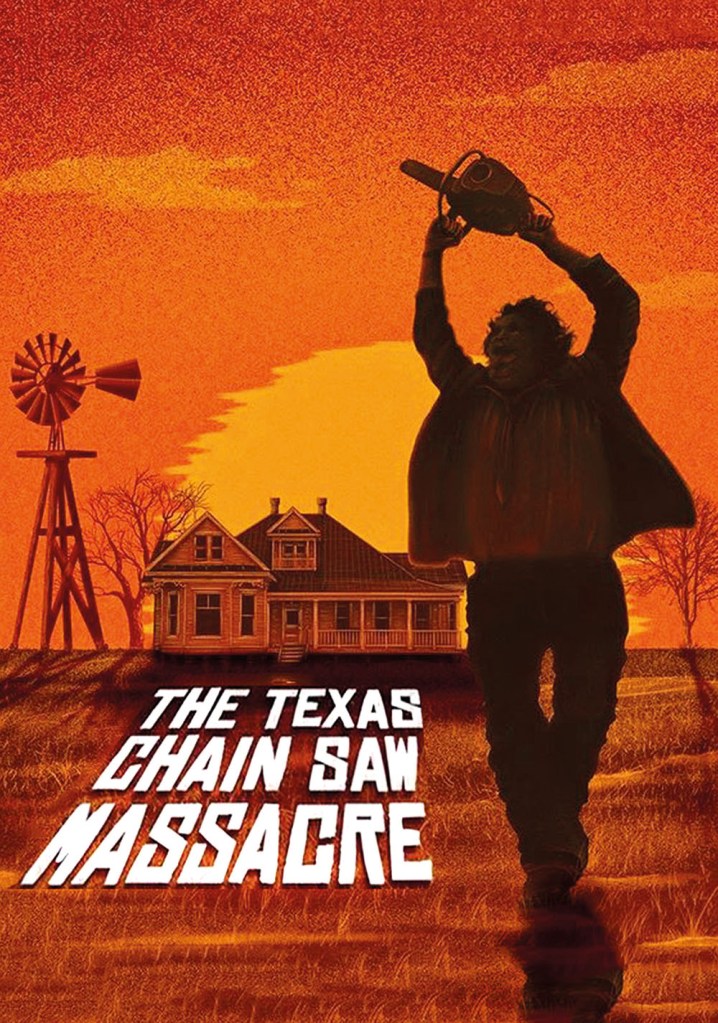

Though billed as a mixture of ‘film theory’ and ‘personal history’, Cinema Speculation is mainly a collection of critical essays about the films Tarantino saw as a child in the 1970s, when his mother used to take ‘little Q’ along on her date nights. Most of those celebrated here – Deliverance, Taxi Driver, The Wild Bunch, Rolling Thunder, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre – strike the reader as grossly eccentric entertainment for a child. ‘I saw a lot of intense shit,’ Tarantino reflects: ‘Just making a list of the wild, violent images I witnessed from 1970 to 1972 would appal most readers.’ In fact, he watched so many violent films that it really does strike the reader as a little unfair when his mother refuses, on rather arbitrary grounds, to let him see The Exorcist, despite her sharing his view that these films weren’t doing him any real harm. ‘I didn’t see Straw Dogs back then either,’ Tarantino laments, ‘but a female child psychologist I had sessions with in school did… When we had sessions we mainly talked about the different movies we saw.’

Tarantino knows an awful lot about films. But it’s not clear he knows much about anything else. I suppose this is why so many of his own films turn out in one way or another to be about other films. Cinema Speculation contains the occasional amusing or striking detail. But this is the result of its being little more than a disorderly heap of details in the first place: a hoarded nest of pet observations and insider trivia that Tarantino, with his anorak mentality, feels too possessive about to bring under any general control for the reader’s benefit.

As a child, he kept files and index cards of all the films he saw and at the end of the year would do his own ‘little awards’. Those index cards, the reader senses, have been brought out of storage recently. We learn about the obscure B-movies he watched, at which cinema, and in a double or triple-feature with what else; what candy he ate; which bits of the films he ‘didn’t dig’; which bits ‘blew [his] little ass through the back wall of the theatre’ (usually the ‘dynamic blood-all-over-the-walls climaxes’); which bits scared him and which merely bored him.

It is difficult to avoid concluding that Tarantino’s aesthetic development was arrested at some point in early adolescence. He reflects banally at one point: ‘There’s few things funnier to a little kid than a funny guy cussing up a storm.’ One suspects the adult Tarantino wouldn’t disagree. He is, he says, ‘someone who equates transgression with art’. The test of a film’s power lies in its capacity to ‘shock the audience out of their movie-trope-fed complacency’, usually via some vivid demonstration of catastrophic violence.

Channelling – with perhaps not too much difficulty – his child self, Tarantino distributes his idiosyncratic praise and scorn among films according to whether they satisfy his sensational criterion. The 1970 hippie massacre film Joe is ‘a cocktail mixed with piss that’s disturbingly tasty’; Robert Altman’s Brewster McCloud is ‘the cinematic equivalent of a bird shitting on your head’ (presumably a criticism, though in Tarantino’s idiom it can become a little difficult to tell). The scene in which Bambi’s mother is ‘shot by the hunter’ is one of the most unexpectedly shocking, and therefore affecting, of all: ‘I remember my little brain screaming the five-year-old version of “What the fuck’s happening?’’’ By contrast, the inexplicit freeze-frame ending of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid strikes both the child and adult Tarantino as a cop out: ‘They shoulda shown it.’

There is the faint trace of an interesting memoir in Cinema Speculation – those references to the ‘child psychologist’, and his glancing account of living in his early teens with a ‘sketchy dude’ and failed screen-writer named Floyd. Instead, as is sometimes the case with Tarantino’s films, the book has the shape of a series of rather decadent set pieces standing in loose association with one another, and of not having been put in front of an editor. Tarantino is a virtuoso popular filmmaker. Unfortunately it doesn’t follow that a master entertainer speculating at length about entertainment is itself entertaining.

Comments