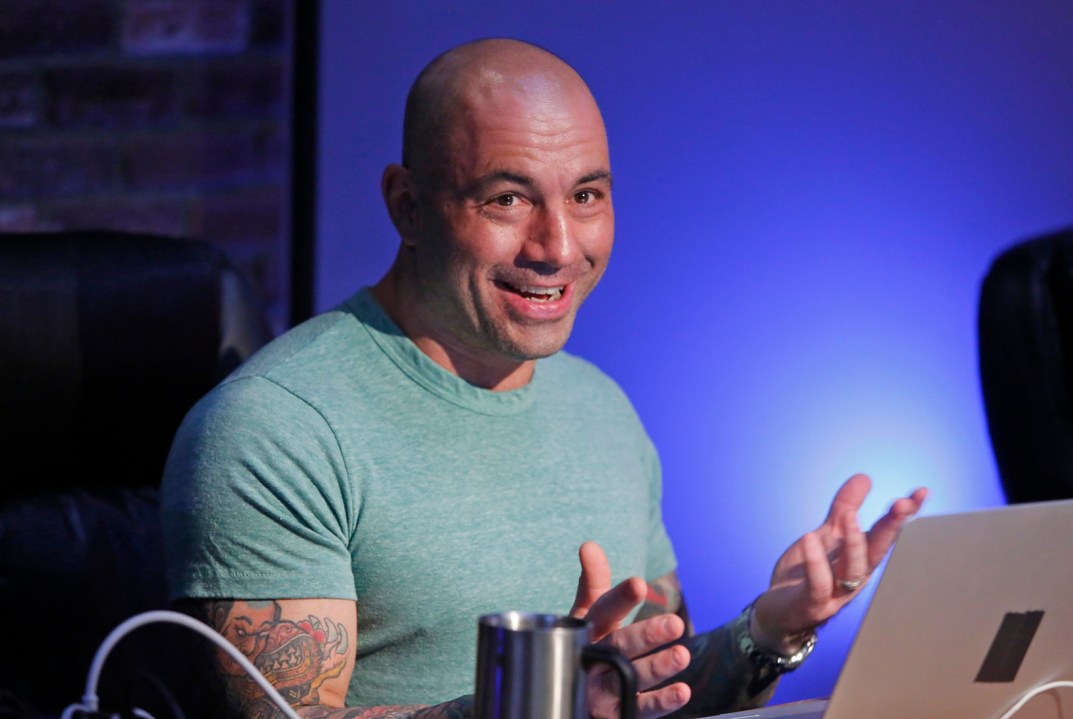

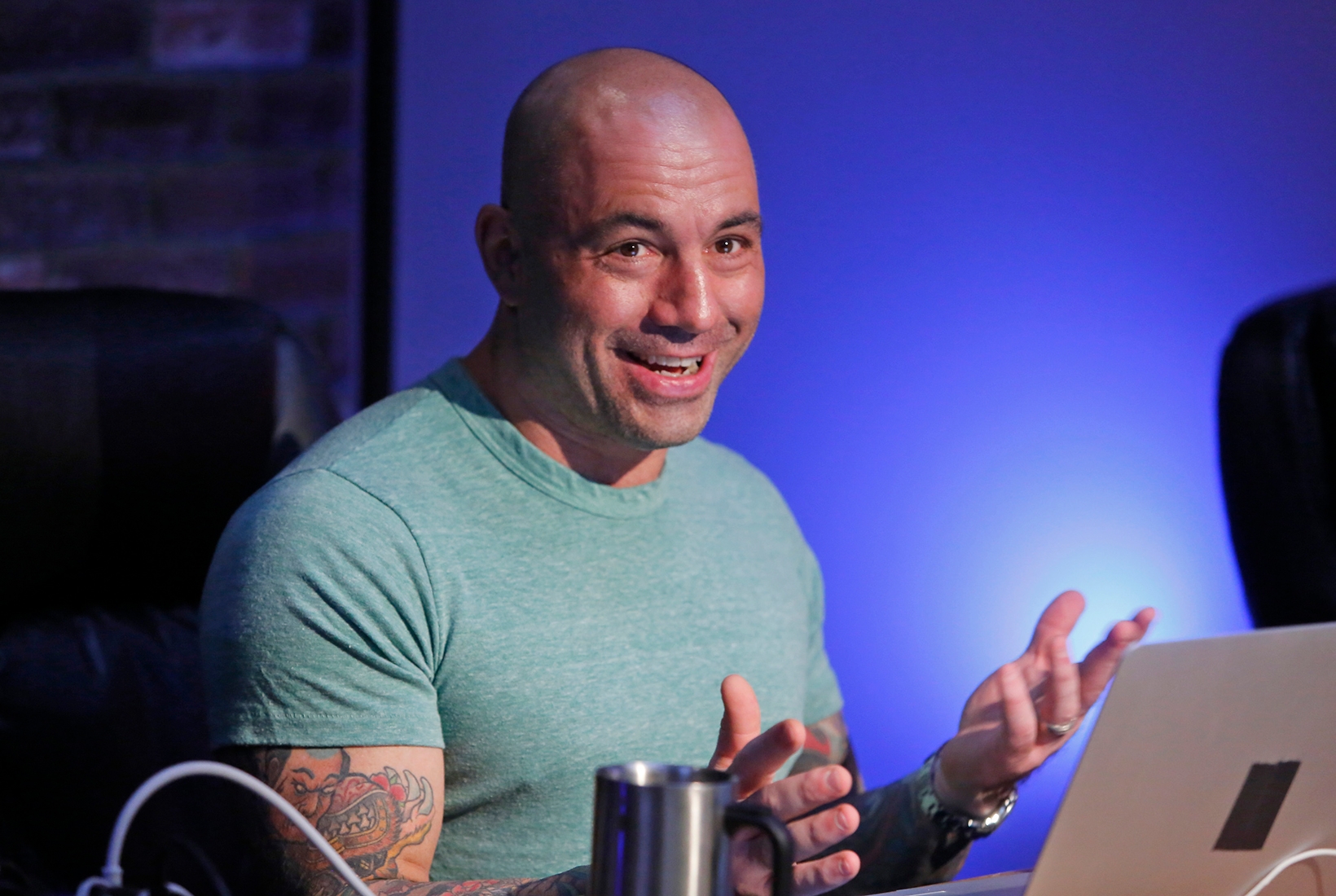

Last month, just before coronavirus conquered the airwaves entirely, millions of Americans gave up two hours to hear a professor of epidemiology discuss the emerging pandemic. Despite its huge reach, not to mention its quality, the interview wasn’t broadcast on any of the news networks. Rather it was the work of a former martial-arts pundit and hallucinogenic-drug enthusiast who also happens to be one of America’s most popular — and influential — podcasters.

Although it racks up some 190 million downloads a month, The Joe Rogan Experience tends to fly somewhat under the cultural radar — particularly in Britain. Even worse, his brash style and predominantly male fan base means that Joe Rogan is sometimes unfairly labelled an arch-reactionary. When in fact — as his even-handed interview with the epidemiologist shows — he’s actually nothing of the sort. So what is he?

As a semi-regular listener myself, I’ve coined my own term for Rogan: the manchild intellectual. How better to describe a man who has a natural aptitude for big ideas — just listen to his two-hour sitdown with the then presidential hopeful Bernie Sanders last summer — but who’s rarely seen out of a crumpled T-shirt and baseball cap? And who occasionally cuts off his guests — Sanders included — to show them video clips from YouTube?

For someone accused of toxic masculinity, Rogan is a mighty good listener

The slacker style has its advantages. Unlike the vast majority of pundits, Rogan isn’t afraid to admit his ignorance of a topic or ask basic questions. When he learns something new, he makes no effort to hide his surprise (several times in the epidemiology episode he lets out a gobsmacked stoner ‘woooow’ that makes you wish he were a little more self-conscious). And for someone accused of embodying toxic masculinity, he’s a mighty good listener.

All this provides a good formula for getting guests to let their guard down. Take Professor Osterholm, the epidemiologist, a man who’s probably spent decades providing scripted answers to reporters. After 30 minutes with Rogan, the professor had relaxed completely, explaining the pandemic as he might to a friend in a pub.

This approach admittedly doesn’t always work. For whatever reason — and this is no small flaw — Rogan rarely clicks as well with women. Likewise his lack of preparation can be a problem. When he interviewed the illusionist Derren Brown, Rogan’s cluelessness was all too obvious. Add Brown’s natural bashfulness — and his British aversion to recapping his own achievements — and the first half-hour became a strange guessing game with Rogan scrambling to establish what his guest actually did.

But what intrigues even more than the discussions is Rogan’s fan base. When I asked on social media who else listened to Joe Rogan, three friends replied immediately. All were brainy, yet none had gone to university or moved to London. What did they like about the podcast? Rogan’s engagement with big ideas — and the opportunity to exercise their intellect.

This, if I’m correct, is the main constituency for Rogan’s podcast: curious young men in small towns who might otherwise struggle to get their intellectual kicks. Of my friends who are fans, all said that Rogan had got them interested in topics they wouldn’t have expected to enjoy (although one flagged Rogan’s coverage of US politics as an exception). Two said they had been inspired to read more about things they’d heard on the podcast. That’s surely good news?

I suspect I’m not the only one to have figured this out. The podcast is a huge hit with advertisers too. It turns out the manchild market — disposable income and minimal commitments — is quite the goldmine (just look at how nerd paradise Games Workshop — and the gamer energy drink Monster — have performed on their respective stock markets). If you’ve got a high-tech gizmo to push, this is the place to do it.

Interestingly, Rogan isn’t the only podcaster riding this wave of self-education. There’s also Neil deGrasse Tyson (an astrophysicist), Sam Harris (a neuroscientist) and Eric Weinstein (a mathematician and ally of capitalist supervillain Peter Thiel), all of whom draw millions of listeners with podcasts focused on big ideas. But what they lack — deGrasse Tyson’s endearing joviality aside — is Rogan’s accessibility. When they interview specialists in some obscure field, it’s usually done from the position of a peer intellectual.

Rogan, on the other hand, treats the role like that of the companion figure in Doctor Who: a relatable human stand-in for us clueless mortals.

Take Harris’s own interview with an infectious-disease specialist last month on his podcast Making Sense. It’s brilliantly informative, but lacks that common touch. Ten minutes in, I had to pause to look up something called an ‘arnot’ which was coming up a lot. After several fruitless searches, I finally discovered that Harris was in fact referring to an R0 (‘r-nought’) — a scientific term referring to the number of people a typical patient will infect. I suspect I’m not the only Rogan listener who got lost at that point.

Comments