Picture the young aspirant with the portfolio of drawings pitching up nervously at the eminent artist’s studio, only to be turned away at the door by a servant; then the master catching up with him, inviting him in and delivering the verdict on his portfolio: ‘I seldom or never advise anyone to take up art as a profession; but in your case I can do nothing else.’

Within two short years of this fairy-tale meeting in the summer of 1891 between Edward Burne-Jones and the 18-year-old Aubrey Beardsley, the self-taught insurance clerk who had fallen under the Pre-Raphaelite spell had turned himself into the most talked-about artist in London. Van Gogh made history in a brief ten years; the consumptive Beardsley, who didn’t choose the manner of his death, had to be quicker. From the moment he set his heart on ‘oof and fame’ there was a breathless urgency to his ambition, disguised under an affected lassitude.

Beardsley easily outbid Wilde in shock value. Three of his drawings were rejected by the publisher as indecent

With, by his own description, ‘a sallow face and sunken eyes, long red hair, a shuffling gait and a stoop’, Beardsley had that essential quality, charm, that opens doors. It didn’t work on William Morris, who sent him away with a flea in his ear and a recommendation to pursue his talent for drapery, but it did on almost everyone else. Career opportunities fell into his lap. It started with the chance lunchtime meeting with J.M. Dent in 1891 in Frederick Evans’s Cheapside bookshop — where the bookish City clerk traded drawings for books — leading to the commission to provide knock-off Burne-Jones illustrations on the cheap for a new edition of Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. Then came the introduction to Lewis Hind as he was launching The Studio and the publication in the magazine’s inaugural issue in 1893 of ‘J’ai Baisé ta Bouche, Iokanaan’, the shocking image of Salome with the head of John the Baptist that would hook Beardsley the commission from ‘decadent’ publisher John Lane to illustrate the first English edition of Oscar Wilde’s banned play the year after.

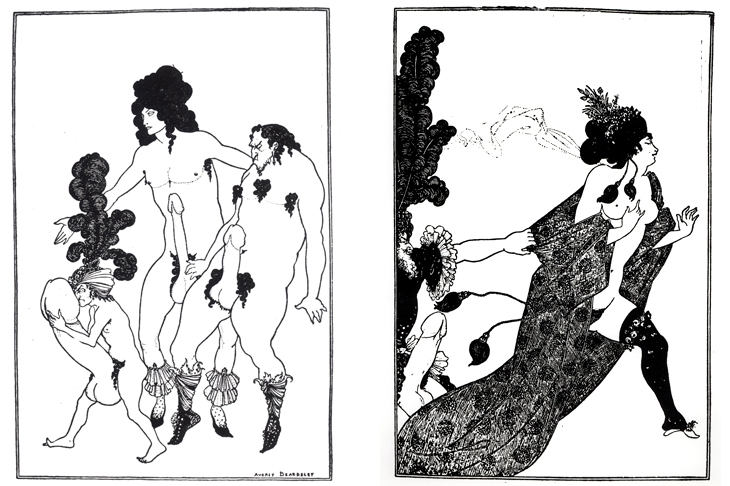

Beardsley didn’t need to work his charm on Wilde, who welcomed him to the fold of fin-de-siècle enfants terribles with a copy of the newly published French edition of the play inscribed: ‘For the only artist who, besides myself, knows what the dance of the seven veils is.’ But when the English edition came out with Beardsley’s illustration of the dance of the seven veils renamed ‘The Stomach Dance’, it became clear that the fledgling illustrator was sending Wilde up. Combining his intimate knowledge of the more graphic Greek vases in the British Museum with his more recent study of Japanese Shunga prints, Beardsley easily outbid Wilde in shock value. Three of his drawings were rejected by the publisher as indecent, and the rest were dismissed by the peevish author as ‘the naughty scribbles a precocious schoolboy makes on the margins of his copybooks’.

Wilde, who knew a thing or two about naughty boys, wasn’t far wrong. The frail shy boy who made himself popular at school by drawing caricatures of the masters had developed an impish compulsion to make graphic mischief. It gave a mocking curl to his whiplash line and turned sinuousness into insinuation. There’s no end to the innuendo in a Beardsley drawing: even his vegetation sprouts double-entendrils. But it’s all good dirty fun, ‘a combination of English rowdyism and French lubricity’, as the Times reviewer observed in 1894 of the first edition of The Yellow Book. The only disturbing element are the foetuses that make their first appearances among ‘the strange hermaphroditic creatures’ in ‘Bons-Mots’ in 1893, and re-emerge three years later on the cover of The Savoy in the form of a sprite-like page who, the artist hinted darkly, was ‘not an infant but an unstrangled abortion’.

Frank Harris later started a rumour that Beardsley had had an incestuous relationship with his sister Mabel leading to a terminated pregnancy, but I suspect the ‘unstrangled abortion’ was an alter-ego designed for critics who felt he should have been strangled at birth. Beardsley invited rumours, and they continue to swirl. Was he on drugs? Not habitually, if we believe the account of him collapsing in hysterics after trying hashish in Paris in 1896. Was he as gender-fluid as his figures? There’s no evidence that he was homosexual, a word that only entered the English language in 1897. W.B. Yeats remembered him rolling up drunk after breakfast with a ‘two-penny coloured’ trollop following his sacking from The Yellow Book, staring into a mirror and saying: ‘Yes, I look like a Sodomite. But I am not that.’

It was Beardsley’s bad luck that Wilde was seen leaving the Cadogan Hotel on his arrest in 1895 with a yellow volume under his arm, reported to be a copy of The Yellow Book. Since he had pronounced the first edition ‘dull and loathsome, a great failure’ that seems unlikely, unless if was his revenge for not being invited to contribute. If so it was well calculated; after a stone-throwing mob attacked the publisher’s Vigo Street offices the next day, Beardsley lost his art directorship of The Yellow Book and had all his drawings thrown off the fifth edition. It didn’t stop him moving later that year into the now notorious flat at 10/11 St James’s Place that Wilde had used as a garçonnière to entertain rent boys, as if deliberately courting controversy. Yet two years later when, terminally ill and convalescing in Dieppe, he was invited to dine with Wilde, just released from prison, he never turned up: ‘A boy like that, whom I made,’ protested Oscar. ‘No, it was too lâche of Aubrey.’

Beardsley’s last months were a catalogue of collapses and convalescences in a succession of unlikely health farms and rest homes: his illustrations to Lysistrata were dashed off in the Spread Eagle Hotel, Epsom, in a three-week period during which he also wrote his will. He finally ran out of road in the Hôtel Cosmopolitan in Menton, a health resort he had previously refused to visit after hearing that ‘but for the occasional funeral there would be no life in the place’. His funeral in March 1898 brought the place to life, with the entire hotel following the procession to a solemn Requiem Mass in the cathedral. (A few months earlier, he had converted to Catholicism — ‘the only religion to die in’, according to Wilde.) He was 25.

Van Gogh’s ten years paved the way for post-impressionism, expressionism and modernism; Beardsley’s seven, apart from influencing art nouveau, left a legacy only of Beardsleyism. He was all but forgotten until the V&A’s 1966 exhibition exploded on to the altered consciousness of the Love Generation, spawning a spurt of album covers, psychedelic posters, logo graphics and fashion styles, led by Granny Takes a Trip and Biba. William Morris was right about the draperies; today the dandified creator of ‘The Black Cape’ might have been a dress designer. That would have been a sad loss to the art of illustration and the art of outrage, for which Beardsley had a particular genius. Let’s hope contemporary audiences for Tate Britain’s new show can still find cause for offence in his naughty scribbles. There are always people prepared to take offence in every generation, but there will only ever be one Aubrey Beardsley.

Aubrey Beardsley is at Tate Britain until 25 May.

Comments