On 11 November 1743, the most sensational trial of the 18th century opened in the Four Courts in Dublin. The plaintiff, James Annesley, claimed that his uncle, Richard Annesley, the sixth earl of Anglesey, had robbed him of immense estates in England and Ireland worth £10,000 a year. The scale of the theft and the rank of the alleged thief would by themselves have made the case exceptional. According to Viscount Perceval who was present, it was ‘of greater importance than any tryall ever known in this or any other kingdom.’ But what really attracted attention was James Annesley’s allegation that in 1727, the year he became heir to the earldom, his uncle had had him kidnapped and shipped to America as an indentured servant, and thereby stolen the title.

Undoubtedly Anglesey was a rotter. He married bigamously, lied, cheated, and bullied, and in a tawdry, beggarly fashion that scandalised the tolerant morals of fellow peers. He borrowed money that was not repaid, cut down valuable timber on estates that were not his, and left his bastards unprovided for. Anglesey was, said one lord, ‘the greatest rogue in Europe’.

Nevertheless, aristocrats were part of government, and not easily displaced. When the wicked earl took to calling young James ‘the pretender’, it asscociated his claim with that of Charles Edward Stuart’s to be the rightful king. The implications were obvious to a 1740s audience: if one pretender was allowed to take an earl’s coronet, why shouldn’t another take George II’s crown?

At the trial, however, a trail of evidence revealed the full extent of the villainous earl’s campaign against his nephew. It began when he hired two ruffians to bundle the 12-year-old boy onto a ship bound for America, and bribed the captain to present him in the colonies as a ten-year, indentured servant, effectively making him a slave for that time. Nevertheless, when the young man at last returned, his barely credible story was immediately believed. Alarmed, the despicable earl was about to negotiate a compromise when an extraordinary accident handed him what seemed a trump card.

While out shooting, James killed a poacher. On Anglesey’s instructions, his lawyer bribed a witness to say that the young man had levelled his gun at the victim. James was charged with murder, and liable to be hanged. But by another switch of fortune, a surgeon took the trouble to probe the wounds, and their trajectory confirmed James’s testimony that the gun went off accidentally as he carried it low to the ground. Set free, the pretender went to Ireland where he was immediately acclaimed as the rightful heir. In a final desperate throw of the dice, the psychopathic earl invited James to the races at Curragh, where he arranged not one but two attempts at assassination.

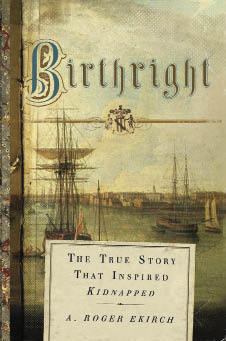

The unfolding of this lurid testimony provides the climax to a splendid story of low skulduggery and high politics, and Roger Ekirch deserves congratulation for disinterring it. As befits an eminent historian, his research is detailed and the evidence carefully weighed, although the style is rather too measured to catch the full stench of rakehell corruption surrounding the case. Nevertheless, it is impossible not to share the general rejoicing when James wins his claim, although the tale twists further before the end.

The author’s care does not, alas, extend to the subtitle which makes the misleading claim, now repeated in Wikipedia, that the Annesley story ‘inspired’ Kidnapped. This is simply wrong, and demonstrably so. David Balfour is indeed kidnapped by his uncle, but the story is about Balfour’s involvement in the killing of Colin Roy Campbell, victim of the real life ‘Appin murder’. The book that actually inspired Kidnapped, according to the unambiguous statement of R.L. Stevenson’s wife, was The Trial of James Stewart, a contemporary account of the murder.

Comments