Raymond Briggs has often spoken of his annoyance at being associated with Christmas. His Snowman may fly across our screens each Christmas day, but in the book there is no Father Christmas, no sleigh, and certainly no figgy pud. The North Pole scene featuring the jolly elf was written into the story for John Coates’s TV adaptation in 1982 and struck Briggs as rather mawkish at the time.

As readers and viewers of Father Christmas know, Briggs’s Papa Noël is anyway rather a grouch at this time of year. As if the cold isn’t enough for him to contend with, there are the chimneys, the tasteless presents, and, oh yes, ‘blooming Christmas’ itself. If he had a favourite character, you could bet it would be Scrooge, and a favourite song, ‘Fairytale of New York’. Anyone with a more suitable list of ingredients for Christmas 2020 can send it to C-19, Humbug Way.

Briggs, now 86, has been called ‘the poet laureate of British grumpiness’. His curmudgeonly persona — ‘a kind of shyness’, says Nicolette Jones, who has just written a beautiful new book on his life’s work — has won him generations of admirers. To the delight of schmaltz-haters everywhere, his crankiness filters through to many of his characters, including my personal favourite, The Man, a minuscule slob who turns his nose up at everything and grumbles when he’s mistaken for a Borrower: ‘Don’t approve of credit.’

Briggs encapsulates perhaps better than any other artist or writer alive the ambivalence that many of us feel towards the season. While claiming to hate it — ‘He likes to play up the “fed up with Christmas” stance,’ says Jones, ‘but anyone who knows him knows he’s extremely kindly and generous and self-effacing’ — he has turned to it more than a few times in his work, and with such success that an association was inevitable.

It began in 1968 when he illustrated The Christmas Book, an anthology of seasonal stories and snippets compiled by the poet James Reeves. Among Briggs’s eclectic cast of subjects were Paddington Bear, propped up in bed with a paper crown flopping over his head and presents spread over his blankets; a nine-foot pie baked with 39 birds in a tin on castors for yuletide in 1700; and Mole looking glum by a fire built by Ratty with a host of carolling fieldmice warming their toes.

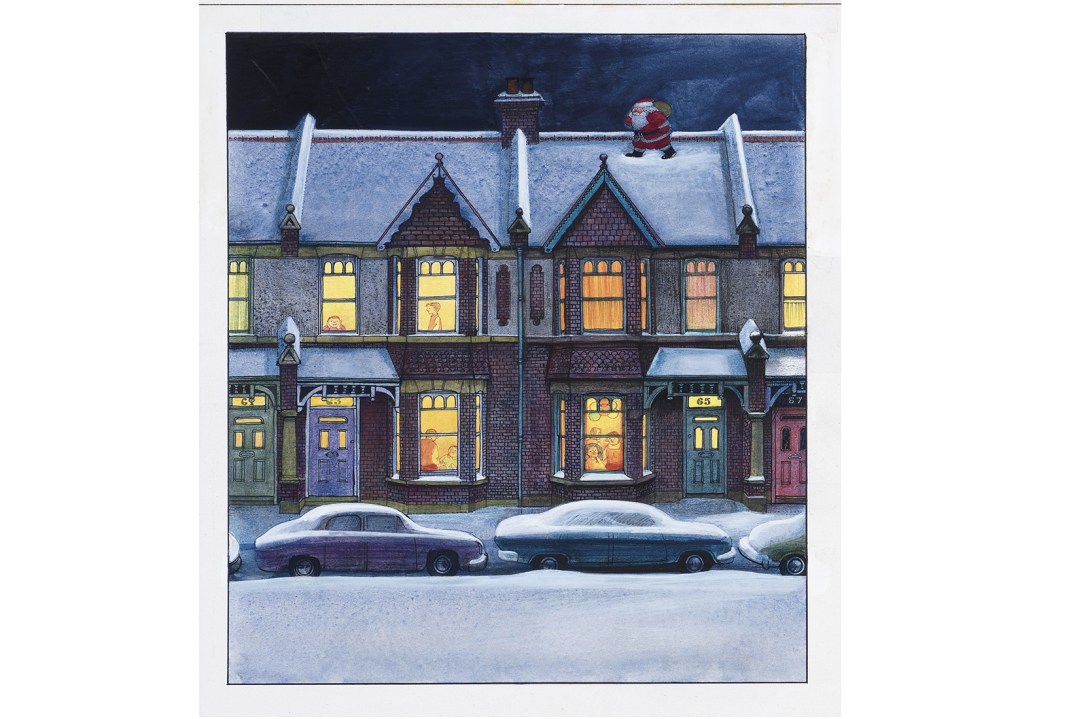

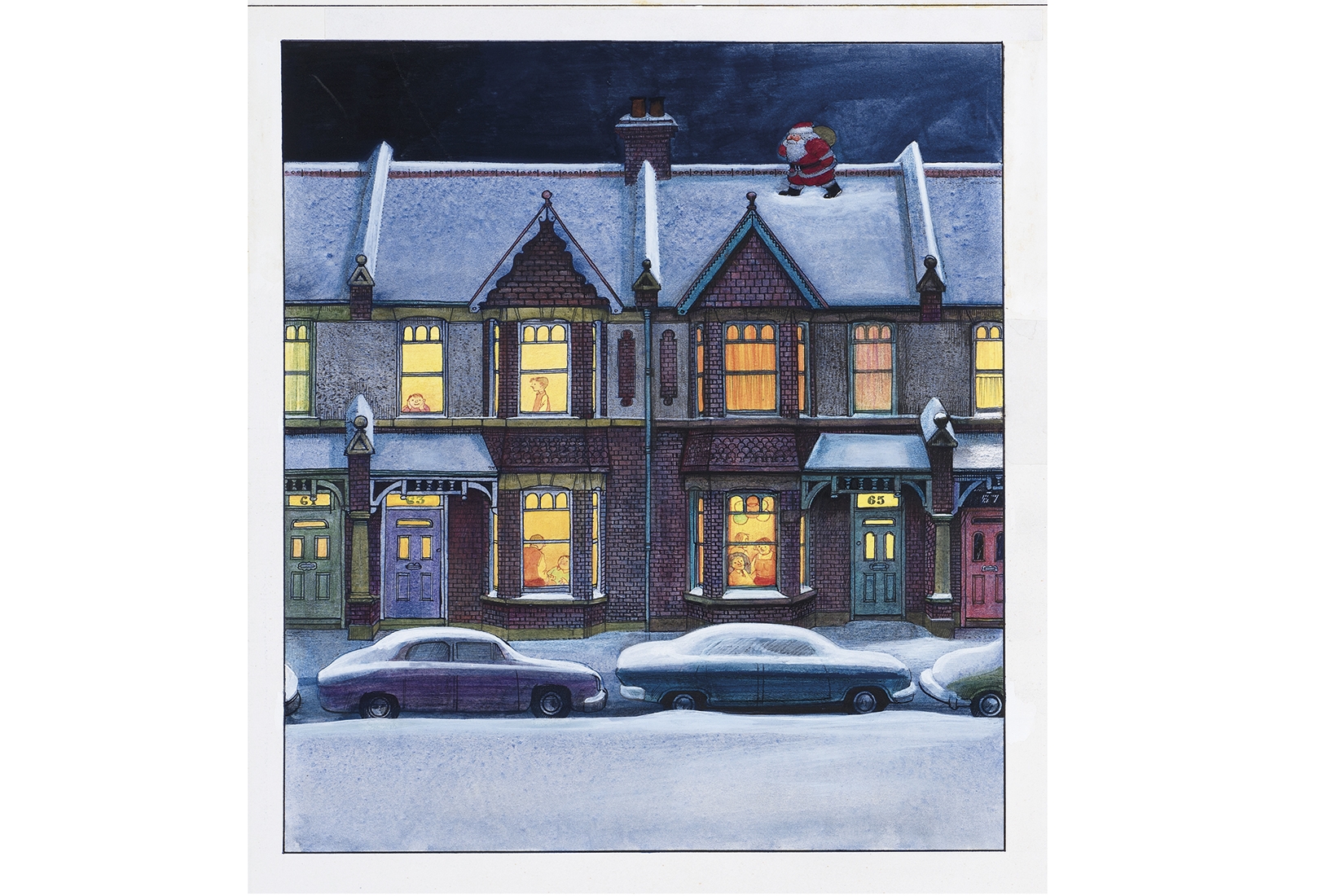

The hearth became a familiar trope in Briggs’s books. His stories may not, on the whole, be very Christmassy, but they do tend to be set in winter. Often, Briggs takes us to his own fireside, either directly, or via the rooftops. In Father Christmas, published in 1973, Santa touches down on Briggs’s childhood terrace in Wimbledon Park and squeezes into the chimney of the East Sussex cottage he has inhabited for the past 60 years. The Snowman recoils from the fire but follows a similar track, soaring over the Royal Pavilion in nearby Brighton, which glows as resplendently as Hagia Sophia (see article by Deborah Ross).

To the delight of schmaltz-haters everywhere, Briggs’s crankiness filters through to many of his characters

Raymond Redvers Briggs, an only child, was born in midwinter 1934 to Ethel, a lady’s maid, and Ernest, a milkman. Long before they appeared as themselves in the deeply moving Ethel & Ernest in 1998, Mr and Mrs Briggs floated in and out of their son’s books like kindly spirits. Believe it or not, Fungus the Bogeyman was inspired by Ethel, whose sweetness is very much at the fore. A less than earnest milkman offers Tilly 20 pints to feed her ursine guest in The Bear and greets Father Christmas with a knowing ‘Still at it, mate?’, as he makes his own chilly rounds. Briggs dedicated Father Christmas to them both following their deaths in 1971.

Briggs has written of his regret at how often people take the fact of having a family for granted. In Notes from the Sofa, a compilation of his witty columns for The Oldie, he jests about inviting his — a lone cousin — to a ‘big family get-together’ for Christmas. Should he hire a hall? Tragically, Briggs lost his wife Jean, who was schizophrenic, to leukaemia the year Father Christmas was published. Liz, his partner since around 1975, passed away in 2015. While Briggs often spends the season with her children and grandchildren, he cannot help but think of those who have no one at this time of year.

Isolation is very much at the heart of his books. Father Christmas has an entire turkey, pudding and ‘party size’ bottle of red to himself. Not too shabby, you think, eyeing his enormous feast. And yet, here’s the chap who enters more homes than anyone else, resigned to spending Christmas day alone, with only his cat, dog, and beloved deers for company. He has just about the loneliest job in the world.

As a child, of course, it doesn’t occur to you to pity him. You are too busy laughing as he brushes his hair and beard simultaneously — separate brushes, please — and rests his derrière on the outside latrine. The young imagination overcomes loneliness by conjuring company out of thin air. Such is the phenomenon Briggs’s books celebrate. Characters emerge fully formed, the Snowman so human that he covers where his genitals should be after trying on some trousers, feeling, like Adam, shame at his nudity for the first time. Only when you reread these books in adulthood do you comprehend the sadness through which imaginary friends may grow and perish.

You may not be surprised to learn that Briggs — who trained at Wimbledon School of Art, Central, and the Slade — is an admirer of Bruegel the Elder. The artist’s peasant-filled winter landscapes have a darkness that permeates the beauty of their setting. Where Bruegel’s snow is so thick it looks unlikely ever to thaw, Briggs’s is as fine as the lines that describe it. Like the imagination, it is transient, destined to melt into puddles, like those of The Puddleman.

These disappointments, often heightened at this time of year, are what Briggs captures best. He cuts through the deceit of nostalgia by reminding us that, for young as well as old, this is as much a season of apprehension and deflation as it is of excitement and celebration. As Nicolette Jones says, his stories have ‘that lived feeling’. He conveys the familiar unease through children’s faces just as Judith Kerr did through Mog, the cat who is so overcome by the festivities that she escapes to the solitude of the roof.

It feels significant when natural light, always so beautifully rendered in his art, is supplanted by artificial light in Time for Lights Out. A simple light switch — like the one the Snowman flicks on and off with such glee — adorns the frontispiece of the book, Briggs’s latest, published just last year. While we gaze or frown at snow-lit skies, it seems to say that there are only so many winters to endure before our own lights are switched off for good. Merry blooming Christmas.

Raymond Briggs by Nicolette Jones is out now from Thames & Hudson.

Comments