In Gerald Weiner’s book The Secrets of Consulting, there is a case study in which a bright MBA graduate tells a giant multinational burger chain to eliminate just three sesame seeds from each bun to save the company $126,000 a year, under the assumption that none of the customers will notice. This works, so the next year they remove five sesame seeds, and, each year or two, they remove some more, until the bun is barely recognisable. Suddenly, nobody buys their burgers anymore.

I get the sense that nothing on the internet really works – or at least no longer works for us

I would suggest that the same thing has happened to the internet. Except instead of removing sesame seeds, we have added them – in the form of adverts, and sponsored posts, and pop-ups, and cookie requests, and tracking notifications, and compulsory registrations, and two-factor authentication, and content farming, and a dozen other digital jack-in-a-boxes. Over time monetisation has triumphed over user experience, and the internet has become increasingly unusable.

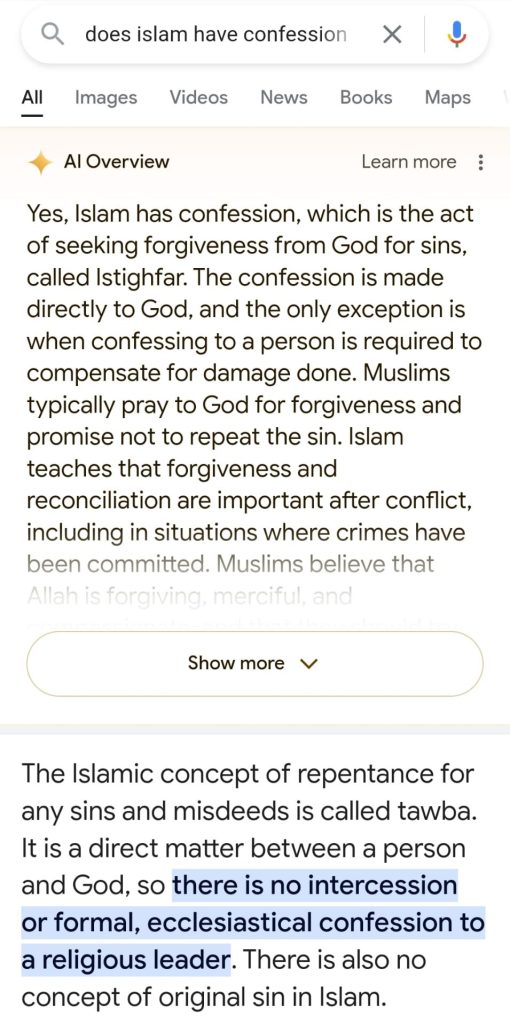

I get the sense that nothing on the internet really works – or at least no longer works for us. SEO hacks and machine learning have all but destroyed search engines, where it is now virtually impossible to get a straightforward answer without some serious scrolling. Google has just started rolling out AI-generated answers to users’ questions. The problem is that, like much AI, the results are often gobbledegook; it would be far more useful to direct us towards the right Wikipedia article (look at the example of Google’s AI answer below versus the relevant Wikipedia article on the topic). Instead, Google is trying to cannibalise the competition by keeping us on its webpages or, at a push, serving up sponsored links that serve no value beyond ad revenue for the firm.

Meanwhile, social media has fundamentally lost the ‘social’ element: Facebook is no longer about catching up with friends and followers, but is simply a graveyard of blurry photos from nights out over a decade ago. Instagram and Pinterest are no longer hubs of creativity but have been taken over by ‘content creators’, while Twitter/X is a playground for trolls and spambots and increasingly irrelevant recommended posts.

The journalist Cory Doctorow has even coined a term for this: the ‘enshittification’ of the internet. Doctorow says that platforms die because first, they are good to their users; then, they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; then finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all their value for themselves.

It might make financial sense, but it’s infuriating. I want to be able to find a recipe online without having to listen to someone’s entire life story first. I want to be able to click on a link without being asked if I would like to subscribe to their newsletter. I want to be able to read an article without feeling like I’m living through some kind of adpocalypse, desperately looking for the tiny ‘X’ button only to find that the ad stays in place even as you scroll down (a Saturday Night Live sketch calls this the devil’s work). I understand that I am the product, but I want websites to at least pretend to be useful, rather than just some convoluted data-mining exercise.

Somewhere along the way, by adding one sesame seed at a time, we lost the childlike optimism, serendipity and connection of the early online world. In the early 2000s, the internet felt like a new frontier. Sure, it was clunky – much of it was built by amateur coders and animators, featuring loud website designs, gawky animations and pixel art – but at least it offered the opportunity for something other than profit and ‘returning value to shareholders’.

Take MySpace, which once had more visits than Google in the US. In many ways, this was the peak of social media, because it was genuinely about self-expression: using basic HTML, you could customise your page to make it completely your own, adding music, games, videos, and other flash content. It was also easy to find people and friends with similar interests (no filtering through algorithmic rabbit holes) and it was full of creators who were genuinely passionate about something and not just trying to sell you a #gifted product.

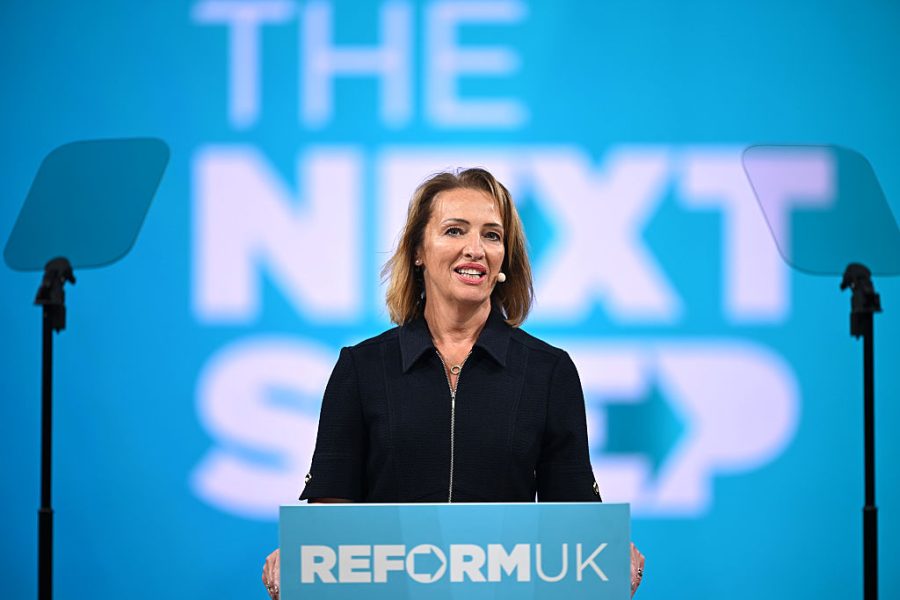

Now, all that individual liberty and community collaboration has been sacrificed at the altar of Big Tech, which has standardised and monopolised the way we communicate, and manipulated virtually every aspect of our lives. Of course there are ad-blockers and other software we can use to try and quieten the noise (I tried to reject all cookies on my phone forever, but then hardly any websites actually worked). Ultimately, though, most of us are just passively accepting the seemingly inexorable degradation of the online world, which will surely only get worse over time. Bumble founder Whitney Wolfe Herde recently said that the future of online dating is having your AI avatar date other people’s AI avatars. If that’s not a reason to spend less time on the internet, then I don’t know what is.

Comments