‘Had I not become a composer, I would have wanted to be a chess player, but a high-level one, someone competing for the world title.’ So said Ennio Morricone, who died earlier this month at the age of 91. Looking back on a lifetime of work, you don’t doubt that he could have done it. The Italian ‘maestro’ was best known for his transcendent film scores; the coyote howl theme from Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, came to symbolise the Italian Western genre.

Less well-known is that Morricone composed ‘Inno degli scacchisti’ (‘Chess players’ anthem’) for the Turin Olympiad in 2006. He was, in fact, a keen chess player, who picked up the game as a boy, but dropped it when it began to interfere with his music studies. Returning to the game in adulthood, he studied with Stefano Tatai, who went on to become a 12-time Italian champion. Morricone recalled games against Kasparov, Karpov, Polgar and Leko, and he even managed to draw a game against Boris Spassky.

In 2016, he won the Oscar for Best Original Score for The Hateful Eight. The music for the opening scene is laden with menace, played as the camera zooms out from a giant crucifix which stands alone in the snow. In an interview with the Paris Review last year, Morricone mused that ‘as I went through the script, I recognised the tension that silently grows among the characters, and I thought of that like the feelings one develops over the course of a chess game… this game is dominated by a spasmodic and silent tension.’ Like Minnie’s Haberdashery, the cabin in the Wyoming wilderness where the plot unfolds, the chessboard is a small but fateful place.

If there were ever a classic game that deserves a musical score, it is this one, in which a future world champion takes on a former world champion. Petrosian, the wily veteran, is saddled with a passive position in the middlegame, but lays out a triad of escalating provocations for the young gunslinger.

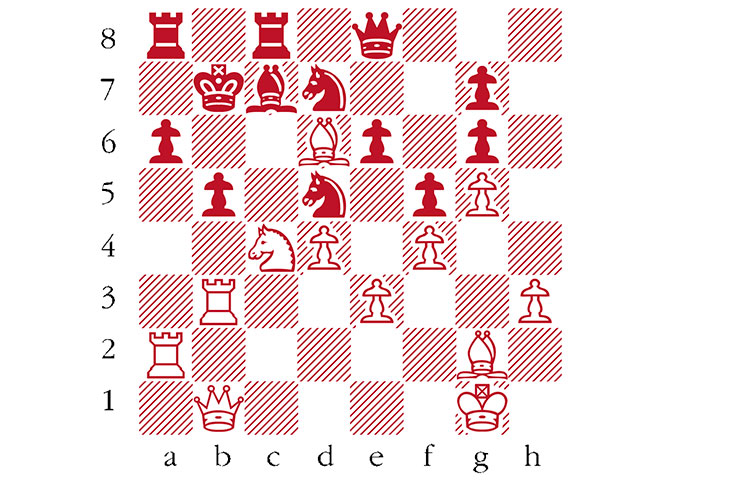

The first is the shrewd pawn-grab 20… Nxb4. It’s risky to open lines for Kasparov’s attack, but Petrosian needs some recompense for his suffering. The second is the gutsy move 30… b5. Petrosian, I imagine, saw a4-a5, Rc2-b2 and Qd3-b1 looming (a heavy piece setup known as ‘Alekhine’s gun’), and favoured fireworks over a slow death. In the third, climactic act of daring, Petrosian dances forward with his king: 35… Kc6!! This dazzling masterstroke confounds Kasparov, whose massed queenside forces somehow cannot touch the exposed king. The path to salvation (36 Bxc7) eludes him and the attack burns out in a desperate flurry. In the final position, the extra horse on d5 snorts proudly. Kasparov is out of bullets, while Petrosian lives to fight another day.

Garry Kasparov–Tigran Petrosian

Tilburg Interpolis, 1981

1 d4 d5 2 c4 dxc4 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 e3 Bg4 5 Bxc4 e6 6 h3 Bh5 7 Nc3 a6 8 g4 Bg6 9 Ne5 Nbd7 10 Nxg6 hxg6 11 Bf1 c6 12 Bg2 Qc7 13 O-O Be7 14 f4 Nb6 15 g5 Nfd7 16 Qg4 O-O-O 17 Rb1 Kb8 18 b4 Nd5 19 Na4 f5 20 Qg3 Nxb4 21 Bd2 Nd5 22 Rfc1 Ka7 23 Qe1 Ba3 24 Rc2 Qd6 25 Rb3 Qe7 26 Qe2 Rb8 27 Qd3 Bd6 28 Nb2 Rhc8 29 Nc4 Bc7 30 a4 b5 31 axb5 cxb5 32 Ra2 Kb7 33 Bb4 Qe8 34 Bd6 Ra8 35 Qb1 (see diagram)

35… Kc6!! 36 Rba3 36 Bxc7 bxc4 37 Rb7 Rxc7 38 Rxa6+! Rxa6 39 Qb5+ Kd6 40 Qxa6+ Ke7 41 Bxd5 Rxb7 42 Bxb7 Qb8 is balanced. 36… bxc4 37 Rxa6+ Rxa6 38 Rxa6+ Bb6 39 Bc5 Qd8 40 Qa1 Nxc5 41 dxc5 Kxc5 42 Ra4 White resigns

Comments