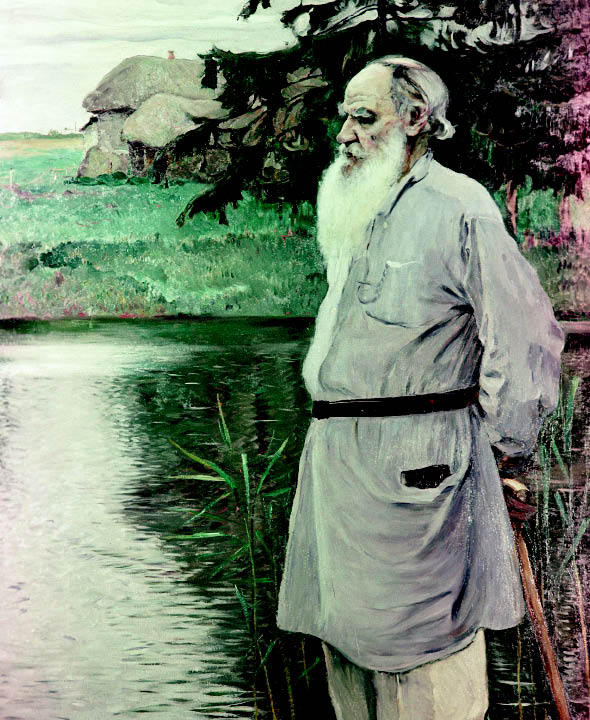

Tolstoy’s legend is not what it was; but sometimes the world needs idealised versions of ordinary men, argues Philip Hensher

The truism that Tolstoy was the greatest of novelists hasn’t been seriously questioned in the last century. The nearest competition comes from Proust and Thomas Mann, I suppose. But when you compare two similar moments in the writings of Tolstoy and one of these other supreme novelists, a difference emerges. Both War and Peace and In Search of Lost Time culminate in a glimpse of the next generation. In Proust, the two irreconcilable worlds of the novel, the Guermantes ‘walk’ and the ‘walk by Swann’s place’ meet surprisingly, at the final party, the bal de têtes, as the daughter of Gilberte and Robert de Saint-Loup emerges from the crowd. She is exquisite, like a museum object — ‘le temps l’avait petrié comme un chef-d’oeuvre’, Proust says. Impossible to imagine her thinking or even saying anything memorable.

Proust has taken this from the marvellous conclusion of War and Peace, where Nicholas Bolkonsky’s son is introduced for the first time; it is clear that his hero-worship of his dead father is going to shape the actions of his future life. The boy Bolkonsky is clearly going to be a man of action. Tolstoy said, very truly, that he was barely a novelist by the standards of his day, since when a character died, he thought first of the reactions of all those around, and for him a marriage was the beginning of the story. At the end of the action of War and Peace we are left with a turmoil of dreams, plans and ambitions in Nicholas Bolkonsky’s bedroom:

‘But some day I shall have finished learning, and then I will do something . . . Everyone shall know me, love me, and be delighted with me.’ And suddenly his bosom heaved with sobs and he began to cry.

For some of Tolstoy’s readers, his life has been an inspiration, almost beyond the value of his fiction — Gandhi and Martin Luther King were steeped in the lessons of non-violent resistance. For others, the life stands in the way of a full appreciation of his mastery. Tolstoy, like no other major novelist, gave up fiction; got to the end of it. Marvellous as the late moral fables are, such as What a Man Lives By and How Much Land Does a Man Need?, they are openly facets of a large pedagogic enterprise, and not, like the major novels, an ethical and artistic endeavour in themselves.

But if Tolstoy had never written fiction, and had limited himself to teaching and social projects, nobody but a few professionals would ever have heard of him. The novels are what really matter, above even the philosophy that the novels explicitly state, which is sometimes frankly misguided and even disproved by the ampler movements of Tolstoy’s art — one thinks of the second epilogue of War and Peace. Nevertheless, the development of Tolstoy’s ideas, and their influence over the world of action, politics and education, are what the biographer will be principally interested in.

Tolstoy must be the subject of more biographies than almost any other novelist, though the most recent in English (I think) was A. N. Wilson’s excellent one some 20 years ago. As time has gone by, voices sceptical about his life’s ambitions have become stronger. One of the most powerful has famously been that of his wife, Sofia (or Sonya, as she was known to her family), whose extensive diaries made a huge impact when they were published in an accessible English edition last year. Her rage at being separated from her husband by the thousands of well-wishers, cranks and hero-worshippers that throngedYasnaya Polyana gave a vividly human aspect to what had seemed a purely spiritual quest. Having married a brilliantly clever and civilised nobleman, who enjoyed the company of literary guests, Sofia found herself having to put up with an aged, vegetarian, Esperantist, anti-capitalist crank, determined to renounce all the worldly goods and copyrights which had made their life together so comfortable and happy. She is vividly caught in this biography, sitting up until three o’clock in the morning, in a rage, trying to erase with one of her diamond earrings her husband’s face from a photograph of him in the company of five ‘Tolstoyans’.

It is fair to say that, in the years after Tolstoy’s death, the view of him which prevailed was the version of Vladimir Chertkov, his devoted secretary. More recently, Sofia’s account has been gaining ground, and seems to me more plausible in its detail and grain. Tolstoy, from a certain point of view, has been rescued from the Tolstoyans, of whom Sofia was never one. But would Sofia’s understanding of her husband, as accurate a perception as it may be of the creative artist, ever have inspired peaceful revolutions in India and Alabama? Sometimes, the world needs idealised versions of ordinary men.

Actually, Tolstoy himself was often rather amused by the Tolstoyans. When in 1893 rumours reached him, before the publication of his principal non-violence tract, The Kingdom of God is Within You, of a Tolstoyan conference, he said:

We’ll turn up to this congress and set up some kind of Salvation Army. We’ll get a uniform — some hats with a cockade. Maybe they’ll make me a general.

Rosamund Bartlett is the author of an excellent life of Chekhov, and this centenary life of Tolstoy is, for the most part, a very accomplished and well-informed biography. She has a confident understanding of the currents and obsessions of Russian society over a very wide span, from the lives of Tolstoy’s ancestors under Peter the Great to the struggles to publish Tolstoy properly under the Soviets and today’s market- dominated Russia.

When it comes to the novels, she fits their ideas firmly within the context of historical trends. In my view, this leads to mixed results. It seems fair enough to place Resurrection against a backdrop of impoverished, ignorant and struggling clergy. But it verges on the comic to comment on Anna Karenina that ‘in his writing, Tolstoy was in some ways following a trend, as it was just at this time that the incidence of suicide in Russia reached what has been described as epidemic proportions.’ And she rather skates over the marvellous late, shorter fiction, amazingly, not even mentioning the greatest of the fables, the 1886 How Much Land Does A Man Need?

She is, however, very strong on the spread of the Tolstoyans, who were quickly setting up sects in places as unlikely as Croydon. Especially valuable is a final chapter which traces both the fate of Tolstoy’s writings in the Soviet state, and the persecution of the poor Tolstoyans. Tolstoy was, of course, a great writer to the Soviets, and his work could be twisted in directions that his fan Lenin approved of — ‘Tolstoy’s Criticism of Capitalism’; ‘Tolstoy’s Criticism of Patriotism and Militarism’. But some un- deniably awkward statements meant that the Soviet edition, embarked upon in 1928, could not be completed until 1958.

The Tolstoyans’ fate was grim. Spied on by the Cheka, they were always apt to be arrested and sent into internal exile. Bartlett has drawn on the apparently remarkable work of Mark Popovsky (which hasn’t yet been translated into English) on their surviving memoirs to show how cruel their lives were. The official line was that Tolstoy should be revered, but his followers persecuted. But officialdom did not always understand quite why Tolstoy should be admired; one informer heard discussion of

someone called ‘Socrates’; the hapless agent noted in parentheses that he did not know him, apparently unaware that Socrates had been dead for some time.

A life of Tolstoy is always going to contain different interpretations, and those who wanted to bend him to their will were always going to be disappointed, from the orth odox church, which excommunicated him, to Turgenev, writing from his deathbed to beg him to ‘return to literary activity’, to poor Sofia, and to the wretched apparatchiks of the Soviet Union. The innate dynamic quality of Tolstoy means that he is not likely ever to stop changing before our eyes.

Rosamund Bartlett tells the story of the failure of these interpretations with knowledge, insight and aplomb.

Comments