At the turn of 2007, the United States was facing defeat in Baghdad. Shia and Sunni were on killing sprees, the supply line from Kuwait was under constant attack, and F-16s were in action on Haifa Street, less than a mile from the fortified US embassy.

Yet commanders in Iraq, and civilians from Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld downwards, clung to a bankrupt strategy: withdraw US forces to colossal operating bases outside town — Camp Victory, Camp Liberty — and leave the streets to an untrained Iraqi army, the sectarian national police and to the thieves and murderers. Meanwhile, success was measured in body count whatever the cost to the population, summed up by Col. Michael Steele of the 101st Airborne, ‘Anytime you fight, you always kill the other sonofabitch’, and by the military scandals of Haditha and Abu Ghraib prison.

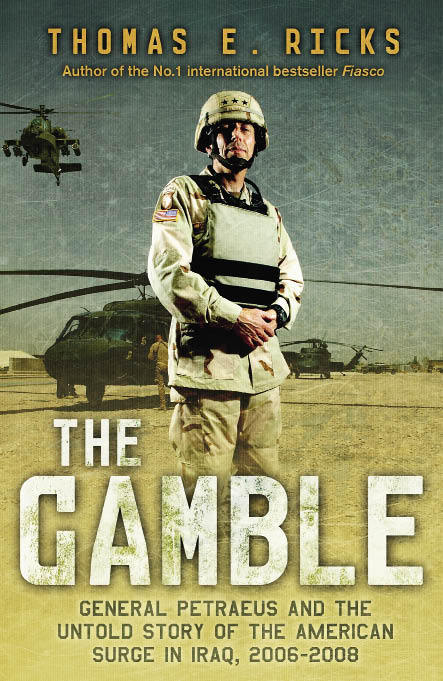

In this fine book, Thomas E. Ricks, an experienced military correspondent for the Washington Post, tells how two professional soldiers, Gen. David H. Petraeus and his deputy, Lt. Gen. Raymond T. Odierno, changed the course of the war. The one a lean military philosopher, the other a bullet-headed fighting general, they by-passed the chain of command, going behind Rumsfeld and the joint chiefs of staff, direct to the President and Vice-President. By the way, George W. Bush is presented by Ricks as a far more capable commander-in-chief than anybody in this country had imagined.

The new strategy, known as the surge, consisted not so much of the five extra fighting brigades that started arriving in February 2007 but of a recognition that Iraq was in the throes of civil war and that the key to success was to protect the Iraqi population. That meant not to move out of but into the city and ‘stop commuting to war’ in heavily armoured vehicles. In his Commander’s Counterinsurgency Guidance to his men of 21 June 2008, Gen. Petraeus got it in one: ‘Walk.’ In February 2007 with the arrival of the first surge brigade, 19 new outposts were established in Baghdad.

Odierno, notorious as a division commander for sweeping up Iraqi males and dumping them in Abu Ghraib, had had his Damascene moment. ‘I looked back: what would Saddam Hussein do?’ What Saddam did to protect himself in the 1990s was to place his best forces in the belt of troubled towns around Baghdad and devolve power to the western tribes, which is also what Petraeus and Odierno did.

It helped that officers such as Col. Sean MacFarland had begun winning over the Sunni tribes in Ramadi and the Euphrates valley against the insurgency, a process known as the Anbar Awakening. It helped that eventually Rumsfeld left, and with him what a State Department official called ‘the commissar school of management, leading with a pistol from the back’.It helped also that Petraeus promoted a more realistic definition of victory. As he said in his April 2008 testimony to Congress, ‘We’re not after Jeffersonian democracy. We’re after conditions that would allow our soldiers to disengage.’

For four months, the battle hung in the balance. In the thicket of interviews in this book — use-’em-or-lose-’em is the journalist to his notes — there are Thucydidean touches: MacFarland in Ramadi ordering every man to fill two sandbags before each meal for the move into town, Petraeus’s agony from old wounds during the interminable Congressional hearings, a dead soldier with an iPod headpiece in his ear so he did not hear the sound of mortal danger. The high point is Ricks’s magnificent account of the fight at Tarmiyah, north of Baghdad, in February 2007, where 38 men of the 1st Cavalry held off a ferocious attack in the ruins of the police station and lost two dead and 29 wounded.

For the British reader interested in military affairs, this book is no pleasure. Just as Petraeus and Odierno were adopting ‘British’ counterinsurgency doctrine, the British abandoned it, withdrawing from Basra City and taking no effective part in the chaotic but succesful Iraqi campaigns last year to retake Basra and Amara. If the surviving purpose of our engagement in Iraq was the good opinion of Americans, on the evidence of this book, boy, is that good opinion gone.

Did Petraeus and Odierno succeed? Well, American military deaths in action fell from 126 at the height of the surge in May 2007, to 12 last month, but two suicide bombings in early March inspire no confidence. A brilliant tactical success, the surge may well have been a strategic failure.

As Emma Sky, an Englishwoman on Odierno’s staff and the Gertie Bell of this story, explained to Ricks: ‘You could buy time and space for the government of Iraq, and it wouldn’t reach accommodation because the system isn’t capable of it.’ (Sky’s account of the surge is in the Royal United Services Institute Journal of last April, Vol 153, No. 2, and costs £4.) Ricks ends with the ominous sentence: ‘The events for which the Iraq war will be remembered probably have not yet happened.’

Meanwhile, Petraeus has moved to Central Command in Tampa, Florida, overseeing the military not only in Iraq but in Afghanistan and Pakistan, where a Pushtun insurgency is gaining Iraqi scale.

James Buchan’s latest novel, The Gate of Air, is published by the MacLehose Press.

Comments