If you lived in the 1760s and were affluent enough – and curious enough – science could be a family affair. The instrument maker Benjamin Martin actually marketed scientific equipment for amateurs, complete with an instruction manual listing simple, edifying experiments for home enjoyment. And so in 1768, in ‘An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump’, Joseph Wright (1734-97) painted a group of family and friends attempting Experiment 42 in Martin’s manual. You’re sure to have seen it: a darkened room with a white bird wilting in a glass bulb while the faces of the participants – a magus-like scientist, a fashionable couple, a frightened little girl burying her face in her dad’s coat – are half-illumined in a pure, almost supernatural light.

So, you’ve seen it: but what did you see in it? Wright’s paintings invite you to create stories, and few artworks hold a mirror to their viewers more brightly than Wright’s candlelit visions. At a lecture in Wright’s home town of Derby last year, the art historian Bendor Grosvenor took a straw poll on whether the bird (a cockatoo) in the air pump lived or died. The audience split almost evenly. In its time, Wright’s ‘Air Pump’ has been explained as an allegory of the Enlightenment, a critique of cruelty, a bravura showpiece by ‘Britain’s Caravaggio’, and (since the go-ahead 1960s) a celebration of the Industrial Revolution then gathering steam across the North Midlands landscape in which Wright chose to live and work.

But as Christine Riding observes in the catalogue to this new exhibition at the National Gallery, the terms ‘Industrial Revolution’ and ‘Enlightenment’ were coined in the 19th century. Neither would have meant much to Wright. To paraphrase Michael Hofmann, any great work distorts its creator, and the candlelight paintings that form the focus of this small but potent exhibition belonged to a brief and relatively early period of Wright’s career. Around half of his paintings are actually portraits, realised with deep sympathy as well as truth and a technique comparable to Gainsborough. Later, Wright concentrated on landscapes, bathing the Peak District and Lakeland in a transfiguring radiance.

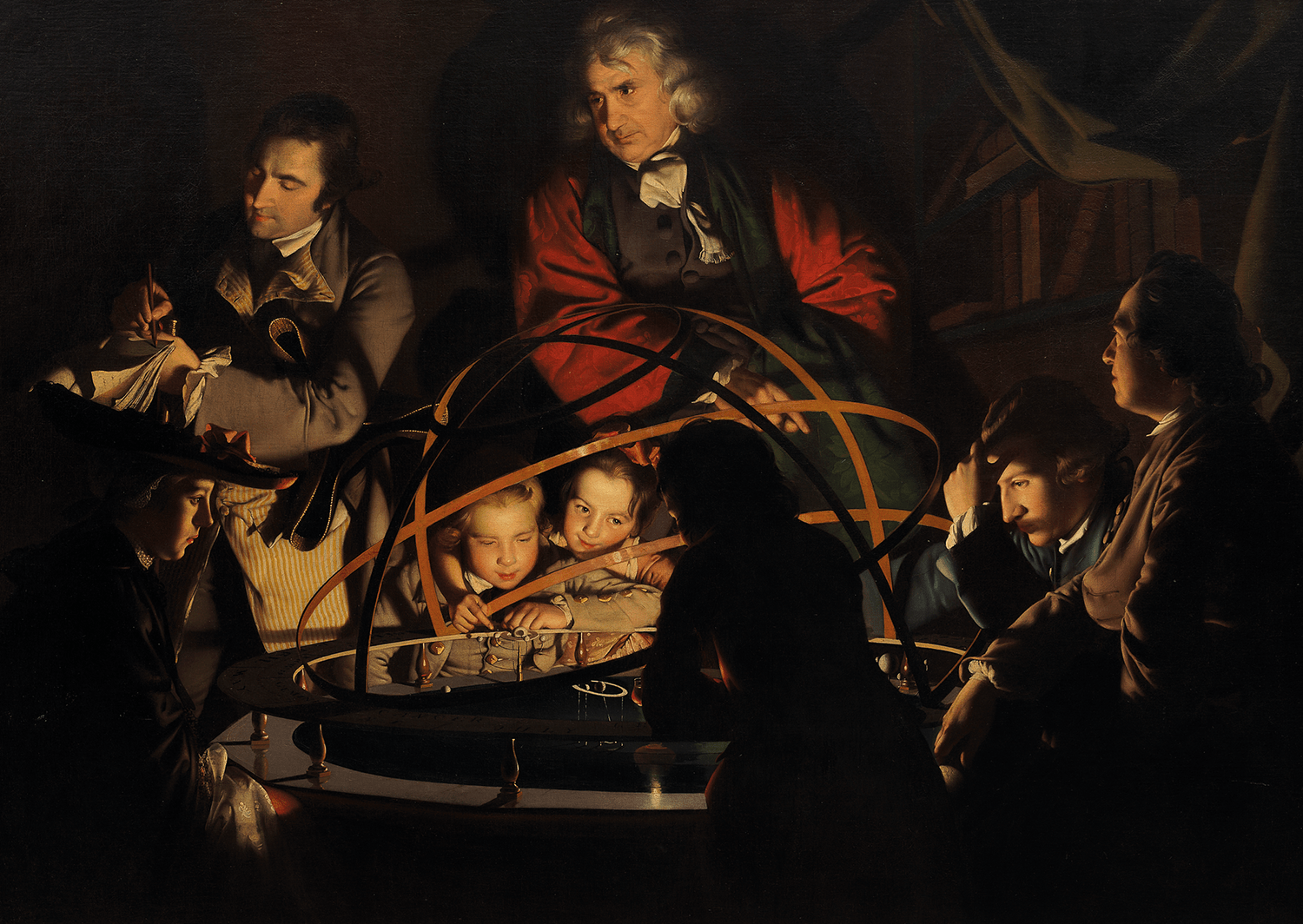

One of his finest landscapes, the tempestuous ‘Earthstopper on the Banks of the Derwent’ (1773), is displayed here, but the main purpose of this new exhibition is to assemble those early studies of light and darkness in an unprecedented concentration. Above all, for the first time in decades, we’ll get to see the ‘Air Pump’ alongside its majestic counterpart (there’s evidence that Wright conceived them as a pair), ‘A Philosopher giving that Lecture on the Orrery in which a Lamp is put in the Place of the Sun’, which usually hangs in Derby. In fact, the exhibition is produced in partnership with Derby Museum and Art Gallery, and it will transfer there next year.

That’s news to make a Midlander’s heart leap. In a climate of cuts and anti-elitism Derby has invested fearlessly in its Joseph Wright collection, reclaiming him as a source of civic and regional pride. To enter the room devoted to his work in Derby is one of the most sublime experiences on offer in any European gallery. In that small grey-walled space, the vivacity and the vibrant, penetrating luminescence of Wright’s paintings springs from the walls, flooding the eyes with a living sense of the man and his vision.

The room showing his work in Derby is one of the most sublime experiences on offer in any European gallery

There’s also the fact that this is art experienced in its home context. London connoisseurs respected and acclaimed Wright, but he didn’t reciprocate, and believed himself snubbed by the Royal Academy. At one point, he even participated in a sort of Georgian secession. The professional name ‘Wright of Derby’ (adopted early in his career to avoid confusion with another Wright) became a self-fulfilling prophecy as he returned home to the Midlands, victim to exhaustion and a recurring depression which – with an art historian’s hindsight – seems to explain much about his fondness for dark and nocturnal subjects.

That’s too easy, though. Darkness is inexpressive without light, and biography is a slippery guide to a genius as complex as Wright. Here in the Midlands, admittedly, his world can feel deceptively close. I live in Lichfield, near the house of Wright’s friend and physician Erasmus Darwin; a stroll to Tesco takes me past the cellar where, in October 1762, Dr Darwin dissected a freshly hanged criminal for the instruction of his fellow citizens. Wright lived in an intellectual hotspot at a time of radical innovation, and Jenny Uglow’s The Lunar Men presents him as an unofficial court painter to the circle around Richard Arkwright and Josiah Wedgewood; leaders of thought and commerce in a period when the counties between the Severn and the Derbyshire Derwent were effectively the Silicon Valley of the 18th century.

And yet Wright’s biographer Matthew Craske demonstrates that the artist showed no great curiosity in science or industry for its own sake. He sought the patronage of earls as well as mill-owners. Any attempt to project schematic narratives on to works like ‘The Orrery’ or the ‘Air Pump’ simply limits their power, and heaven knows, Wright has been too readily pigeonholed. In The Invention of British Art, Grosvenor records that as recently as 1958 a catalogue at the Tate insisted that Wright was a minor master: that ‘the word “provincial” should remain attached to him in the derogatory as well as in the flattering sense’.

Blind snobbery, of course. Gaze into the solar whiteness of the hot metal in Wright’s ‘A Blacksmith’s Shop’ (1771), or observe the wonder (a near-sculptural sensitivity to human expression) that Wright finds in a subject as mundane as ‘Two Boys Fighting over a Bladder’ (1767-70), and it’s obvious why Wright of Derby hangs in the Hermitage and the Met. If these are ‘provincial’ subjects, they’re provincial only in the way that Shakespeare’s Forest of Arden belongs to Warwickshire, or that Vermeer portrays Delft.

That unflinching, melancholy genius, knew that where the eye leads, the mind follows and the heart speaks

Wright took as his motto a maxim by the French art theorist Charles Alphonse du Fresnoy: ‘Nature, which is presented before your eyes, is a better mistress. For She augments the force and vigour of the Genius, and She it is from whom Art derives her ultimate perfection.’ In other words, the local really does contain the universal. The model for the sage-like philosopher in another candlelight painting, ‘Three Persons Viewing the Gladiator’ (1765), was ‘Old John’ Wilson, the head waiter in a Derby pub. When Wright toured Italy between 1773 and 1775, friends noticed that he sought out the landscapes that looked most like Matlock Tor.

Wright looked at his world with intense closeness and clarity; we get to participate in his vision and perceive our own mysteries. So, does the bird in the air pump live or die? Craske and Grosvenor both point out that if you actually read Martin’s instructions, the answer is clear. The bird appears, briefly, to die, but with the readmission of air it suddenly revives. ‘By these experiments, it is plain that there is such a thing as a temporary death,’ wrote Martin – and certain details that are obscure in the original painting are easily discerned in a contemporary mezzotint copy (also in the exhibition). A spray of condensation can be seen as the life-giving air re-enters the glass, and a church is visible outside the window.

Wright’s parable of cold rational progress, it seems, is actually a proof of the Resurrection. The dazzling fires of his forges and volcanoes are not an expression of elemental terror, but a glimpse of the almighty intelligence behind Creation itself. Or is that simply how we choose to read Wright’s work in our own unhappy, post-scientific moment: an affirmation of a resurgent age of faith? Either way, the pictures endure; still alive, still puzzling, still wreathed in that cosmic darkness. ‘Bold eccentric Wright, that shuns the day,’ mocked one contemporary, but Wright, that unflinching, melancholy genius, knew that where the eye leads, the mind follows and the heart speaks. It’s our turn, now, to follow him towards the light.

Wright of Derby: From the Shadows is at the National Gallery until 10 May 2026.

Comments