Anyone with a passing interest in old British buildings must get angry at the horrors inflicted on our town centres over the last half-century or so. Gavin Stamp is wonderfully, amusingly, movingly angry. And he has been ever since the early 1960s when, as a boy at Dulwich College, he saw workmen hack off the stiff-leaf column capitals in the school cloisters.

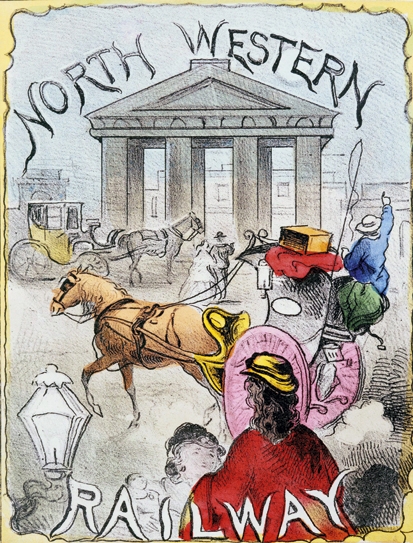

He reserves particular rage for that ‘cynical, philistine Whig’ Harold Macmillan for murdering the Euston Arch. Not that Stamp’s a ranting fogey, reserving his anger only for the demolition of Victorian buildings. A former chairman of the Twentieth Century Society, he is deeply upset by the demolition of the 1936 Guinness Brewery in Park Royal, west London — a restrained exercise in industrial jazz modern by

Giles Gilbert Scott, the man who designed Battersea Power Station and the phone box.

Even when you disagree with Stamp’s views, they are always well-expressed and peppered with intriguing facts— as when he tells you that the vast walls of the Guinness Brewery were built out of millions of special 23/8 inch Wellington facing bricks, separated by 5/8 inches of carefully tinted mortar. And how gripping to know that Pugin died on the same night, in the same county — Kent — as the Duke of Wellington, meaning that the great architect’s death was largely eclipsed.

Stamp regularly surprises, too. You might have thought he’d be a fan of Anti-Ugly Action — the 1958 activists’ group that campaigned outside two new buildings they hated: Caltex House in the Old Brompton Road and Agriculture House in Knightsbridge. But he doesn’t share their views, and he positively hates the idea, proposed in 2005 by the then President of Riba, that there should be an X-list of buildings worthy of demolition.

The Anti-Ugly Action group lend their name to the first of these two books by Stamp. It’s a misleading title for this collection of engaging articles for Apollo magazine; it suggests a series of Prince Charles-style attacks on new buildings. Stamp’s range is much wider and less predictable than that. In fact he attacks ‘the Xerox-Palladian Prince of Wales school of classicism’ and, in particular, the Prince’s tendency to regard anything with a flat roof as bad, anything with columns as indisputably good.

Palladianism — which I’d always thought of as a reliable, inoffensive option — is ‘that perennial curse of English architecture’.And Stamp also thinks undue reverence is given to the architecture of country houses, thanks to English snobbery. He even comes round to Nikolaus Pevsner’s view that all architects should work with the Zeitgeist if they want true originality and architectural success. In another surprising revelation, he credits Pevsner, and the Victorian Society, of which Pevsner was chairman, for doing more to save St Pancras than John

Betjeman.

It’s not all anger. Stamp is prepared to admit that, sometimes, as with the 1854 Carlton Club on Pall Mall, a fine Victorian building can be replaced by a really good 20th-century one. He writes with deep admiration, too, of the funniest of all architectural artists, Osbert Lancaster, and his creation of more architectural vocabulary than any writer before or since: from Stockbroker Tudor and Aldwych Farcical to By-Pass Variegated.

The second book is the paperback of Stamp’s heart-rending 2010 compendium of lost Victorian buildings. It is largely a gazetteer of those sad losses, with a long introduction that comprehensively demolishes the old anti-Victorian prejudice, best caught by P.G. Wodehouse in Summer Moonshine (1938):

Whatever may be said in favour of the Victorians, it is pretty generally admitted that few of them were to be trusted within reach of a trowel and a pile of bricks.

Sombre pictures of the lost buildings in their prime prove quite how deft the Victorians were with the trowel. How they make one long for a time machine to return to the pre-wrecking days.

Comments