For me this book evokes a Gigi duet moment: ‘You wore a gown of gold.’ ‘I was all in blue.’ ‘Am I getting old?’ ‘Oh, no, not you.’ Memory plays us false, and it takes the skill of a sympathetic historian such as Virginia Nicholson to sift the evidence, written and oral, and unfold a story that is both plausible and sound.

I look back to my 1960s life and think how many of us were metaphorically clothed in gold… how we strode through the years enjoying new freedoms, new loves, music, clothes, drugs, opportunities. I have in my time contributed to the myth of unalloyed pleasure, extolling the 1960s for the quickening pace of change, the broadening mood of happiness and hope. But, as another lyricist has it, ‘it ain’t necessarily so’.

Nicholson meets the dilemma head on. There have been fine histories of the decade by David Kynaston, Dominic Sandbrook and Arthur Marwick: all of them footnoted, thorough… and male. In contrast, Jenny Diski’s agonising personal account was poignant and female. Nicholson, too, lets her own presence into the narrative. She was only four when the 1960s began: she was taken to watch the wedding of Princess Margaret on a friend’s television. In those days 79 per cent of the population didn’t have a set. Ten years later, in August 1969, she was a disaffected teenager yearning to attend the ‘biggest open air concert in history’, the Isle of Wight Festival just a short journey from home. ‘How could I be alive at such an amazing time and miss out on all this?’ She asked the question then and she asks the question now.

It is her enthusiasm as much as her scholarship that makes this such a beguiling read, especially for those of us who were there at the time and indeed have shared our recollections. In the course of answering her own question she draws on a parade of witnesses now in their sixties, seventies and even eighties, women who in their comfortable retirement remember what it was like in their youth: Mary Denness, one of four Hull trawlermen’s wives who lobbied parliament for greater safety at sea; Nina Fishman, who as an American student was roughed up by police at the Grosvenor Square anti-Vietnam rally and still bears the scars. This is history captured on the wing: soon they will all be gone and the distortions of history will begin to fudge their accounts as much as, perhaps, their cherished memories. But for the moment this is a rich and detailed story, told by those who were there.

The first thing that strikes one is how naive and trusting many of them were, setting off from dull homes around the country to join the high jinks of the glittering capital. Teresa from Cornwall who loved Cliff Richard: ‘I screamed till my nose bled.’ Caroline, who screamed at the Beatles: ‘The screaming was so loud you really couldn’t hear them.’ It becomes clear that it was on the shoulders of those screaming, suddenly liberated young women that the decade’s ethos was built.

The impact of their stories is all the stronger set against their memories of the world they came from: dull, drab, and hierarchical. Conventional fathers ruled tight little homes, while mothers served their every need and kept their daughters ignorant. At puberty, Veronica’s well-intentioned mother gave her a manual about fruit flies! Pregnancies outside marriage — not surprisingly they happened, given the fruit-fly advice — were condemned. The birth of a handicapped child was considered a social disaster.

Meanwhile, the hierarchy of wealth and power prevailed. Nicholson identifies its female emblem as long white gloves: Princess Margaret wore them at her 1960s wedding; debutantes wore them at the marriage market know as Queen Charlotte’s Ball. Those in the 1950s with social aspirations had them too: I still have mine.

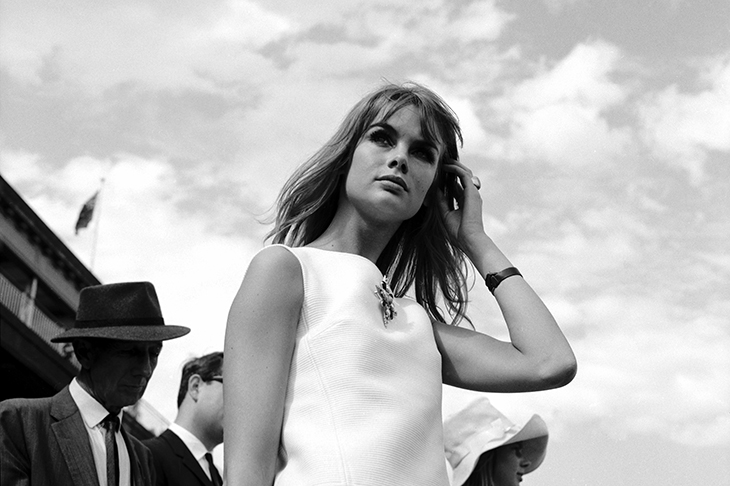

Year on year, through the decade, it was women who directed the changes. It began with clothes. Clothes changed everything: how we walked, stood, danced, played. Suddenly fusty copies of our mother’s stiff stuff were gone. Bright colours and strange fabrics were in, while skirts went progressively shorter. Tights didn’t arrive until later in the decade, so the suspender fetish flourished. John Osborne once told me he didn’t like tights: ‘They restrict access.’ Yes, women were still objects of sexual desire, but once the pill had arrived they shared enthusiastically in the new sexual freedom.

Nicholson’s story carries many accounts of how much fun it all was. The word ‘fun’ crops up so often you wonder quite what it was. Laughter, music, sex, parties, drugs? Increasing amounts of all, perhaps… many at the same time. But then the story clouds. The laughter starts to sound hollow. Women were changing, and changing fast, and these changes defined the decade. Men were thrilled with the new licentiousness, made wonderful music and simply had their ‘fun’. But the change in men’s behaviour didn’t equal that of the women.

Men still kept their traditional values of power and authority, expecting ‘the little woman’ to serve their needs. Cynthia Lennon recalls how John always left the room whenever she changed a nappy. Men were delighted by the sudden sexual availability of women, and exploited it to the full. Nicholson cites pop lyrics: ‘Light my Fire’, ‘Foxy Lady’, ‘Born to be Wild’. But they themselves didn’t pioneer the new freedoms.

Indeed, the changing morality brought many clashes: Mandy Rice-Davies and Christine Keeler were easygoing good-time girls looking for some fun in the big city. The establishment first enticed them, then used them — and afterwards, when Keeler’s sexual liaisons brought about the fall of the Macmillan government, vilified them. New values made their way into the BBC’s television plays, and then ran into trouble. The social realism of Cathy Come Home and Up the Junction prompted a schoolteacher from the Midlands, Mary Whitehouse, to launch a hugely successful campaign of righteous indignation that attracted thousands to its Trafalgar Square rallies.

And the new freedom began to eat its own. Jenni Diski was one of its casualties: ‘The idea that rape was having sex with someone who didn’t want to do it, didn’t apply very much in the late 1960s. I was raped several times by men who arrived in my bed and wouldn’t take no for an answer.’ It wasn’t all fun. Yet, as Nicholson concludes: ‘The decade may have fostered misogyny, pornography and objectification. But at its best it offered a peace-and-love Utopia that outlawed the constructs of masculinity: intolerance, greed, money and war.’

As the decade progressed, women’s impulse to change broadened from clothes to ideas: and here Nicholson’s heroine is Sheila Rowbotham. In 1967 Rowbotham had joined the East London Vietnam Solidarity Committee and found herself snubbed by its male members. By January 1969, having joined the board of the radical paper Black Dwarf, she produced a women’s issue. She followed it up that summer with a powerful polemic, ‘Women’s Liberation and the New Politics’. The stirrings of women’s liberation had become a movement, and this was its manifesto. Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch would open the next decade.

History moves in great arcs of rising hope and deepening despair. We are currently in despair mode. But the 1960s felt full of hope — and feeling it, we brought it into being. The burdens of life were easing — incomes steady, housing affordable, consumer goods plentiful — so there was a backdrop of security. Indeed, many of the freedoms were most relished by the children of rich or even aristocratic families, provided with the secure incomes that funded parties, foreign travel and, yes, ‘fun’. This economic stability enabled social change and experiment. And it bore the fruits we enjoy today, the biggest social movement of our times: the emergent equality of women.

Comments