In the world of books, a modern classic is an altogether more slippery thing than a classic: it must walk a line between freshness and durability; reflect the current age but hope to outlast it. For individual publishers, given many 20th-century writers are still in copyright, a modern classics list will necessarily be partial. However, few such partial lists are as complete as Penguin Modern Classics (PMCs), founded in 1961 four years after Penguin’s general editor A.S.B. Glover said: ‘We don’t want — without outstandingly good reasons — to start any new series such as “Modern Classics”.’

The outstandingly good reasons were lots of outstandingly good books that weren’t old enough to warrant the status of Penguin Classic but demanded some recognition, or at least some marketing. The first titles in April 1961 included Thornton Wilder’s The Ides of March, Carson McCullers’s The Heart is a Lonely Hunter and Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts.

Now Penguin, never shy of raiding its own archives, gives us The Penguin Modern Classics Book by Henry Eliot, a companion to his Penguin Classics Book (2018). It is essentially a gossipy catalogue of the books, a feast of cover designs and fact-nuggets; and contains every book — more than 1,800 — ever published in the series.

Ah yes, those cover designs. From the start, PMCs have sought to present a stylish face to the world, to look, as Penguin publisher Simon Winder puts it, like ‘a series to be enjoyed, rather than something that is good for you’. The books of our youth are no less evocative than the music, and in browsing this volume you will be drawn magnetically to your own era: for me, it’s the 1990s watery-green-spined Penguin 20th-century Classics look, in which I first read Waugh, Woolf and Greene.

The book is divided by geographical region, from which it’s clear (as Eliot sheepishly acknowledges) that western Europe and America have dominated the series; even now there are only three writers from China and one from North Africa. Trends shift over time: popular semi-literary fiction added now is less likely to be general fiction (Somerset Maugham, Arnold Bennett) and more inclined to be in a genre, such as the gigantic haul of 32 Len Deightons added recently.

These shifts matter because a modern classics list is in the business of not just recognising greatness but conferring it — or at least fast-tracking it. The Ides of March, for example, was only 13 years old when it was promoted by Penguin. (This does not, of course, justify the inclusion in the series of gifted oaf Morrissey’s autobiography, a decision Eliot in a recent interview distanced himself from: ‘Before my time.’)

But in other respects, Penguin’s list dragged its heels. After a century of emancipation, during which Marguerite Yourcenar became the first woman elected to the Académie Française (Jean d’Ormesson observed that the toilet doors would need to be relabelled ‘Messieurs’ and ‘Marguerite Yourcenar’), the list is still only 20 per cent female. But efforts have been made elsewhere: in 2011, only three writers of colour were published in PMCs; in the last year there were 12.

The story of literature is a human story, and it’s the authors as much as the books that fascinate in Eliot’s commentary. In the connected 20th century we can trace six degrees of separation from, say, Ivy Compton-Burnett to R.K. Narayan. Compton-Burnett was friends with Olivia Manning (about one of whose books she nonetheless said: ‘It really is full of very good descriptions. Quite excellent descriptions. I don’t know if you care for descriptions? I don’t’); Manning had, in Stevie Smith, a mutual friend of George Orwell; Orwell went to Eton with Cyril Connolly, who befriended Graham Greene at Oxford; and Greene was instrumental in getting Narayan published.

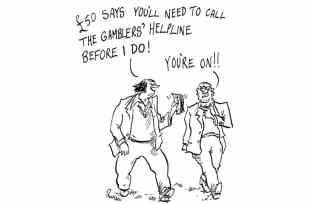

Alcohol is a frequent theme – and a really good death can give a writer’s reputation a little frisson

There are common themes in writers’ lives: ‘alcohol’ appears almost 50 times, and deaths, where a really good one — Boris Vian ‘died of a heart attack while attending a screening of an unsatisfactory film adaptation of his book I Spit on Your Graves’ — can give a writer’s reputation a little frisson. As this suggests, The Penguin Modern Classics Book is at its most entertaining when filling its sidebars with juicy trivia, such as Maugham calling the Angry Young Men ‘scum’, or the Japanese bizarrist Kobo Abe patenting a new brand of snow chains for car tyres. The cross-references — author to author, movement to movement — give it dynamism, forever suggesting new routes.

And just as writers are always joining the modern canon, so other writers fall away: who now reads Richard Pennington’s Peterley Harvest? But its day may come again, just as Dambudzo Marechera’s House of Hunger, out of print since briefly appearing in PMCs in 2002, will be reissued in the series next year. Perhaps one day David Karp will rise again, as future generations are poring overa later edition of this book and asking: ‘F. Scott who?’

Comments