This absorbing book is — in both format and content — a much expanded follow-up to the same author’s very successful pictorial anthology Lost London of 2010. It replicates some of the photographs that appeared there and contains many new ones, all in captivating detail. The photographs are ones of record. There is little sense of artful composition or a striving for special effects. Many are of great beauty in their direct simplicity, as though the images were breathed onto the page with no human intervention. But of course the presence of a photographer with his cumbersome equipment in a slummy alley or dead-end court was bound to attract attention; inhabitants gather; children gawp; men in caps and boaters stand nonchalantly waiting for the click of the shutter; some are caught in the midst of their daily work; others seem to have given life the slip. There are haunting faces, yet it is extraordinary to think that some of the younger people in the later photographs might still be alive, so distant in time do the images appear.

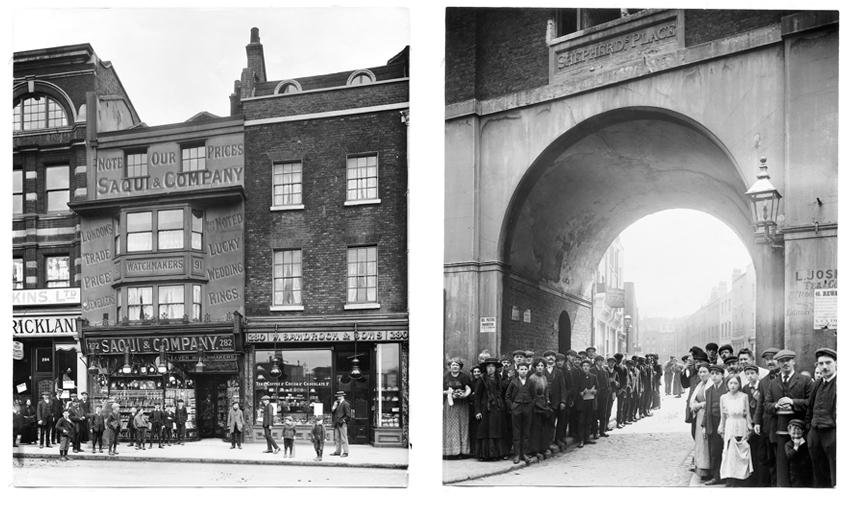

Here are streets that Dickens would recognise (although the Old Curiosity Shop in Portsmouth Street, Holborn, a rare pre-Restoration survival, was not his fictional model). Gissing is invoked in images of the shabby-genteel and the ‘London particular’, as described, for example, in The Odd Women. Going deeper into some of the most wretched quarters, we are in the world of Kipling’s story of Badalia, beaten to death by her drunken husband, of Arthur Morrison’s ‘mean streets’ and Maugham’s Lisa of Lambeth. Here are the shop fronts of backstreet Soho — Conrad’s Mr Verloc is surely behind the window of one of them — and of the Clerkenwell where Arnold Bennett places his bookshop in Riceyman Steps; shops that Sickert would have painted with all their signs, placards and posters forming an exclamatory collage, caught in these photos with minute legibility.

‘Funerals to suit all classes’ on an undertaker’s lamp is one of the more memorable; Batey’s seems to have blitzed the city with a campaign for its lemonade; a barber chalks drawings of available haircuts on his wall; and older readers will click with Saxone shoes painted across a window in 1912. Here too is the West End with magnificent views of the Criterion Restaurant, of the gentlemen’s clubs — an African carving strikes an appropriate, if unusual note in the entrance hall of the Savage Club — the interiors of Admiralty House and (little changed) those of Berry Brothers in St James’s. Here Soames Forsyte crosses Piccadilly ahead of Mrs Dalloway.

Obviously there are districts that are unrepresented because they were not about to be torn down or were not sufficiently historical or picturesque to have attracted the photographers. There is little to the west of Regent Street — a brief foray to the Thames at Chelsea; the Fulham Pottery (not redeveloped until the late 1970s); old houses in Hammersmith; and the exotic rooms of William Burges’s Tower House in Melbury Road. To the north, nothing of Canonbury and Barnsbury nor the squares of Bloomsbury, butchered by London University as much as by the Blitz.

There is an outstanding, highly detailed section on the area demolished to make way for Aldwych and Kingsway, whereby the medieval street plan was mostly obliterated, along with Clare Market where the London School of Economics now stands. Nearby Drury Lane was incredibly down-at-heel in 1906. This area’s tributaries of poverty, their source in Seven Dials to the north, oozed into the broad democracy of the Strand, its tight-packed commercial properties recorded here below the distant ghosts of St Bride’s and St Paul’s on the skyline. Most of Philip Davies’s captions are pointful and informative, although he does not always tell us when locations were demolished. Occasionally he rubs our noses in the degradation of a scene — is ‘poverty stamped indelibly’ on the faces in Bankside in 1912; is the crowd in Spitalfields so sickly and ill-dressed? Nevertheless, the book is a superb contribution to social history, the photos to be ‘read’ again and again; one can only hope there is further material for a sequel.

P.S. In spite of the book’s title, not all is ‘lost’, if we interpret the word in a physical sense. I happen to be typing this review in the Regency terrace of Duke’s Road pictured here (plate 50), a miraculous survival, with its adjoining Woburn Walk, just south of the Euston Road. Its period charm formed much of the setting for the latest Poirot, broadcast on Boxing Day, nearly two centuries after the street was built in the protective shadow of St Pancras Church.

Comments