When the pound plunged a few weeks ago, Andrew Marr opened his Sunday show by saying that this might be a good thing because ‘it had been too high for too long’. It was a minority opinion, and one not seen much in the hysterical reporting of the pound’s plunge. At the Spectator’s post-Autumn Statement briefing last week, kindly sponsored by Old Mutual Global Investors, we raised this a bit. The pound’s fall might make overseas holidays more expensive for Britons, but it also makes our goods far cheaper for the rest of the world. We worry about a worst-case WTO scenario of 10 per cent tariff on cars, for example, but a 13 per cent currency plunge rather makes up for that.

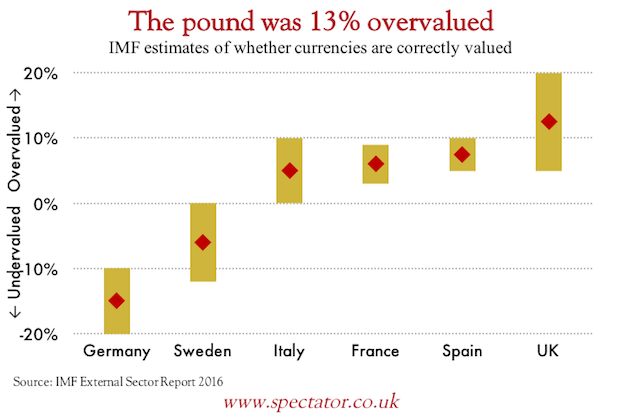

So was the pound overvalued? The IMF carried out a study on this earlier this year, and gave a range – and a midpoint. It found that the pound was about 13 per cent overvalued, which distorted the economy because we’d be more likely to import and (as Liam Fox would tell you) less likely to export. It would also be a magnet for immigration, especially for those seeking to earn here and take money back home afterwards. The IMF also showed why the Germans are so pleased to be in the euro: their currency is about 15 per cent undervalued, making their exports artificially cheap and employment artificially high.

And also, the pound’s fall has so far been along the same trajectory as the 2008 crisis and others – usually followed by a decent recovery.

Comments