For those trying to argue that the evils of colonialism still hang over former lands of the British Empire, the legacy of racism suppressing their ambitions and achievements, the Republic of Singapore presents something of a challenge.

Just how did this particular colony manage to become not only one of the wealthiest countries in the world, but one of the highest-fliers in the United Nations’ Human Development Index? Indeed, the Asian city state has once again this week been promoted as a model for its former colonial master to emulate.

It can’t just be the Guinness that has attracted investment to another former corner of British soil over the past couple of decades: the Republic of Ireland.

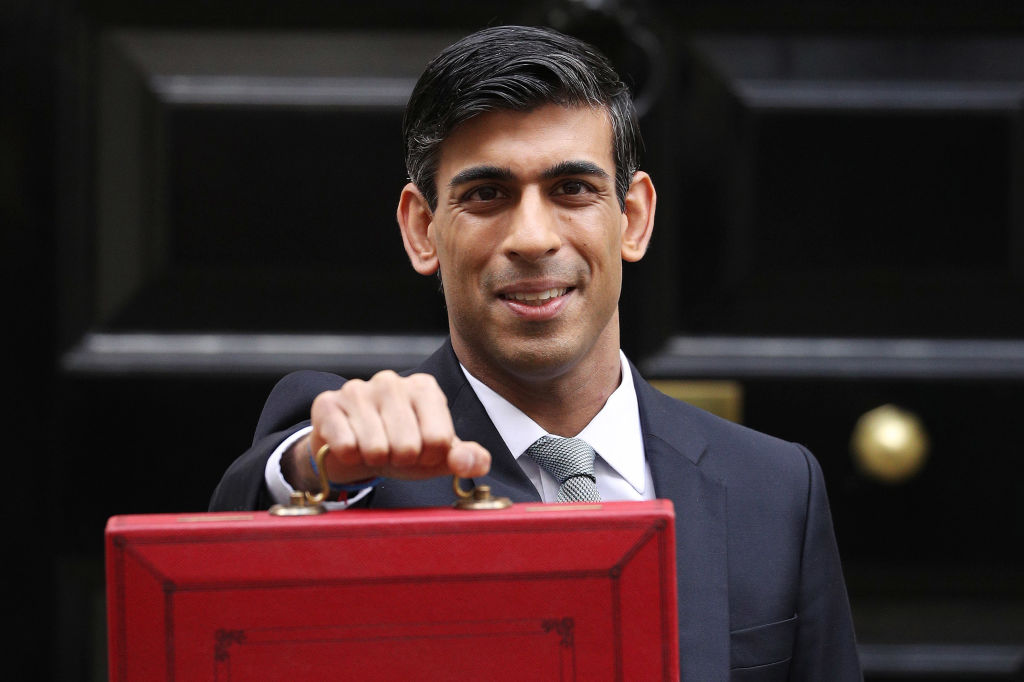

The notion of Britain becoming a European Singapore was raised during and after the Brexit referendum. But if we want to be a Singapore, increasing corporation tax would be a pretty odd way of going about it. The Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, is said to be looking for at least one tax rise for his March budget to show he is serious about trying to get the public finances back into something approaching balance.

With income tax, national insurance and VAT rises ruled out through manifesto commitments, his options are limited. But he is reported to be looking at corporation tax, partly on the basis that there is room for some increase from our current rate of 19 per cent while still remaining competitive with our European neighbours.

Sunak is said to have some evidence that our relatively low rate of corporation tax does not play a large role in attracting businesses to invest here. But then it can’t just be the Guinness that has attracted investment to another former corner of British soil over the past couple of decades: the Republic of Ireland. Like Singapore, Ireland has overtaken us in terms of GDP per capita, and I have a horrible suspicion that Ireland’s corporation tax rate of 12.5 per cent might just have something to do with it. Any increase from Britain’s current rate of 19 per cent is going to make Ireland look even more attractive. It would also take our rate above that of Poland and Slovenia, which are also set at 19 per cent.

Nor is there much room for manoeuvre before UK corporation tax overtakes that of Sweden (21 per cent), Switzerland (21.1 per cent), Denmark or Norway (both 22 per cent). Singapore, by the way, has a corporation tax rate of 17 per cent.

Is Sunak sure, in any case, that a rise in corporation tax would actually increase revenue? The recent history of the tax does not suggest much reason for confidence. In 2007, corporation tax was 30 per cent and raising £41.3 billion a year. The tax rate was then progressively lowered, reaching 19 per cent in 2017. Revenues did fall initially (there was also the small matter of the 2008/09 recession), bottoming out at £33.6 billion in 2011/12.

However, once the tax rate fell below 25 per cent, revenue began to rise. In 2019/20 it was £59.95 billion — £3 billion higher than if it had risen in line with inflation. Why? One reason is that when you have a high rate of tax, corporations have an incentive to divert their profits away from your shores. Lower the rate and you give them an incentive to move them back.

Before the 2019 general election, Boris Johnson proposed to cut corporation tax to 17 per cent, but got cold feet about the political signal it would send: tax cuts for the rich etc. With a deficit likely to reach £450 billion this year, it is not the time for tax cuts, sadly. But we could at least avoid shooting ourselves in the foot by jacking up rates of corporation tax, especially when we are trying to tell the world we are a new Singapore.

Comments