When Samuel Richardson’s Pamela was published in 1740, it unleashed something unprecedented in literary history. This epistolary novel about a virtuous servant girl resisting her predatory master saw new depths of feeling on the printed page, reducing readers across Europe to tears.

The revolutionary impact of emotion informs Ferdinand Mount’s ambitious cultural history, Soft. The former TLS editor and one-time head of Margaret Thatcher’s policy unit has crafted what reads like an elegant love letter to the human heart itself.

Mount grasps an important truth: emotions do not mean the same thing across time, nor are they consistently valued in the same way. What one era celebrates as virtuous emoting, another dismisses as mawkish excess. Mount is very much on the side of feeling, arguing it serves as a social instinct that drives reform. He proposes that three distinct ‘sentimental revolutions’ have swept across society, transforming not merely hearts and minds but everything from legal frameworks and social structures – fuelling the building of hospitals and the abolition of slavery, divorce reform and the legalisation of homosexuality. Drawing upon William Blake’s formulation that ‘a tear is an intellectual thing’, Mount maintains that ‘it is the weight of feeling that carries the argument down the line’.

The first sentimental revolution, according to Mount, began in the 11th century. Following C.S. Lewis’s influential argument in The Allegory of Love, he connects the invention of courtly love to Christianity’s gradual humanisation: the merciful Virgin supplanting stern patriarchal deities, kindly saints proliferating as sympathetic intermediaries between heaven and Earth. This medieval flowering of feeling provoked reaction, what Mount terms the ‘stony age’ of austere Protestantism and neoclassical Renaissance grandeur. Michelangelo’s dismissal of Flemish art as inferior because it encouraged viewers to emote rather than contemplate serves as Mount’s paradigmatic example of this anti-sentimental backlash.

Michelangelo dismissed Flemish art because it encouraged viewers to emote rather than contemplate

But this is mostly prologue to his great passion – the 18th century’s flowering of sentimentality: Richardson’s tearful heroines, Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, Rousseau’s Julie (though Mount brushes off the prickly writer as unoriginal, calculated and cynical) and Henry Mackenzie’s The Man of Feeling, which he regards as the high point of sentimental fiction. He enthuses about the philosophy of David Hume and Adam Smith, who explore the moral dimensions of feeling and the epistemology of sympathy. Here Mount is particularly persuasive about the period’s genuine intellectual achievements while remaining alert to its contradictions.

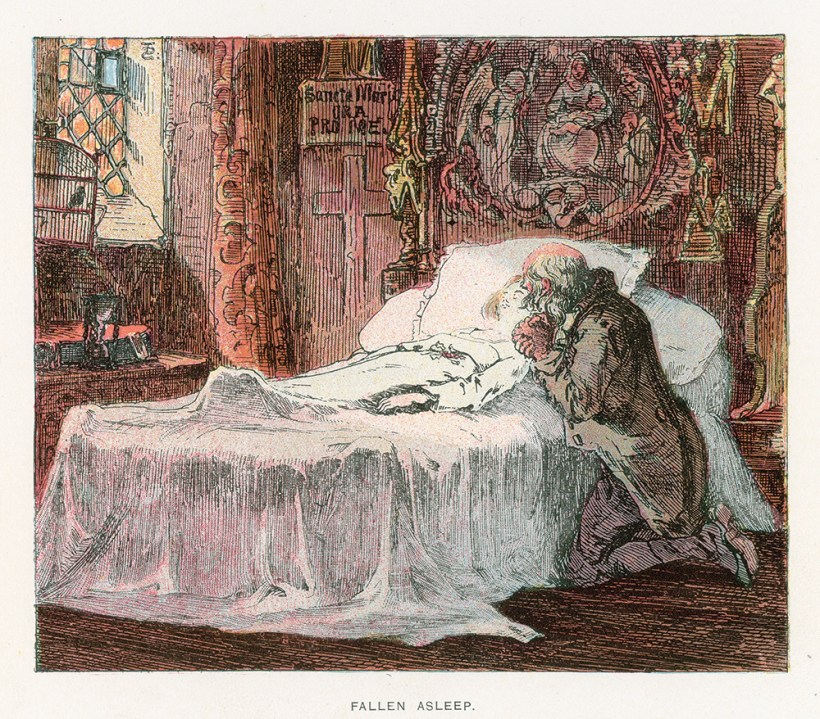

He extends his analysis to later writers such as Dickens, whose overwrought characters and scenes, such as the death of Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop, caused a nation to mourn and Oscar Wilde to quip that ‘one must have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without laughing’. Mount insists that Dickens was derided not because his writing was weak but because it was dangerously effective. So, too, was other literature. A well-worn anecdote claims that Abraham Lincoln, following the outbreak of America’s Civil War, called Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, ‘the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war’.

Arriving at what Mount identifies as the third sentimental revolution – the permissive society emerging in the 1960s and continuing in stages to the present – the argument becomes less dexterous and more of an irritable stomp. What follows reads like a checklist of progressive causes: the legalisation of homosexuality and abortion; the end of capital punishment; the passing of divorce laws – all of which, he suggests, were won by sentiment. Missing here is any serious consideration of the political activism and rational arguments that many social movements advanced, or thoughtful discussion of the opponents to such reforms. Did critics like Mary Whitehouse really just not feel enough emotion?

Mount sees a backlash against sentiment everywhere today. Here, Spectator writers Rod Liddle and Toby Young get a mention, but the evidence suggests that Mount has no reason to fear. While there is criticism of ‘emotional correctness’, the dynamics of our era – where feelings over facts is a rallying cry – suggest that those he calls ‘stony-hearted’ are very much on the back foot. We live in times where emotion floods the public realm and those who do not emote are considered lesser moral beings. Sentiment’s potential dangers do get acknowledgment in the book, particularly how the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror demonstrated how feeling could turn monstrous. But this insight doesn’t extend to today’s world.

The book opens with Paul McCartney’s question ‘What’s wrong with being sentimental?’. But this might have more force if McCartney hadn’t needed John Lennon to add necessary grit and levity to his sweeter impulses. The problem is not sentiment per se, but sentiment unmoored from reason. Feeling without accompanying rationality becomes not moral force but narcissistic self-indulgence – or worse, a kind of emotional tyranny that shuts down genuine public discourse in favour of untested individual feelings.

Like the finest love letters, this tribute to human feeling proves most persuasive when passion enhances rather than eclipses judgment – a balance the work achieves in its historical sections but loses when sentiment leads the author to mistake our current emotional turbulence for enlightened progress.

Comments