This week marks the 81st anniversary of the Japanese attack on the US fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, which launched the start of the Pacific War and turned what had hitherto been a European war into a world conflict. The air attack by 353 Japanese warplanes on the US fleet at Pearl Harbor was led by flight Lt Commander Mitsuo Fuchida. His later conversion to Christian evangelism was one of the peculiar outcomes of this seminal event in 20th Century history.

In the summer of 1984, I was on a small car ferry taking me from Matsuyama, a city on Shikoku, the smallest of Japan’s major four islands, to Hiroshima, situated on the main Japanese island of Honshu. It was a journey that had a transformative effect on my future. It was here that my life intersected in a virtual sense with Mitsuo Fuchida.

It was a calm, warm summer’s evening, the sun was setting over Japan’s magical Inland Sea with its tree-covered myriad of islands. Why was I the only person deck? Inside, the saloon of the ferry was crowded with Japanese passengers watching ‘Tora! Tora! Tora!’ (Tiger! Tiger! Tiger!) the multi-Oscar nominated joint US-Japanese film which portrayed Japan’s infamous surprise attack on the US fleet. It was the code sent by Mitsuo Fuchida to Admiral Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, aboard aircraft carrier IJN Akagi, that signalled the success of the surprise attack. Fuchida’s character played a starring role in the film.

On the ferry I had watched the film astounded as, every time a moored American battleship was hit, the watching Japanese screamed ‘Banzai’, an abbreviation for Tennoheika Banzai, meaning ‘Long live his majesty the Emperor’. Particular appreciation was given to the scenes showing the blowing up and sinking of the USS Arizona, in which 1,102 Americans died. How different the post-war Japanese attitude to the second world war was to Germany’s. It was the episode on the ferry that eventually spurred me to abandon my financial career to write about modern Japanese and Asian history.

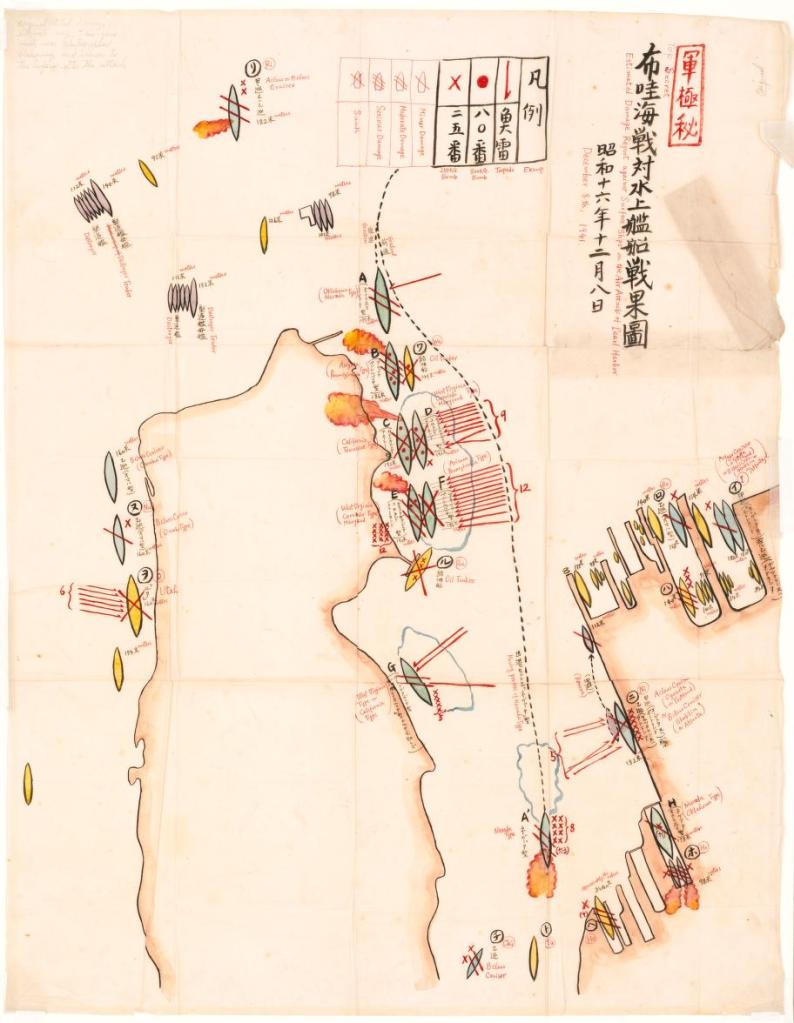

For Fuchida, Pearl Harbor was the start of a career defined by narrow escapes. At Pearl Harbor he stayed behind after leading the first wave attack to monitor the second wave and to map out the damage to the US navy. This small map, exquisitely detailed and coloured, was sold by his family for $430,000 in 2014 and later acquired by the Library of Congress. Filling in the map almost cost Fuchida his life. His badly shot up Nakajima Type 97 torpedo bomber’s controls had all but been destroyed. He was luckier than most of his crew – nine out of ten were killed before the end of the war.

Fuchida later served in carrier strikes against the British in Sri Lanka and an attack on Darwin in Australia. Most significantly he was present at the defining aircraft carrier Battle of Midway on 4 to 7 June 1942. Here the US Navy, aided by the breaking of Japan’s naval codes, scored a fluky yet crushing victory against the Admiral Yamamoto’s Imperial Japanese Fleet. Four of his six fleet carriers were sunk in the space of minutes with the loss of just one US carrier. It was a blow from which Japan could never recover.

Again, Fuchida’s luck held. Struck down by appendicitis on board, Fuchida could not take part in a battle and had to watch the ensuing US attack from the aircraft carrier’s bridge. The attack by Dauntless dive bombers from USS Enterprise, USS Yorktown and USS Hornet cost the lives of 3,057 Japanese sailors and airmen.

On the sinking and on fire IJN Akagi, Fuchida had to clamber down from the bridge on red-hot ladders until he could hold on no longer. He jumped onto a lower deck and broke both his ankles before being helped from the burning carrier’s only escape route to the nearby light cruiser IJN Nagara.

Forced by his injuries to take a desk job, providence again favoured Fuchida. On 5 August 1945, the day before the dropping of the first atom bomb, Fuchida was meant to be in Hiroshima for an officers’ conference but was called back to Tokyo. This saved his life. All his fellow attendees died.

Afterwards he was sent back to Hiroshima with colleagues from Tokyo to report on the effects of the bomb. The Japanese government knew about nuclear bombs; Dr Yoshio Nishina, who had worked with the eminent theoretic physicist Niels Bohr in Denmark, had established a nuclear facility at the Riken Institute in 1931 and had built Japan’s first cyclotron. Quite recently workable designs for a Japanese atom bomb have been found at Kyoto university in the Radioisotope Research Laboratory. However, neither American nor Japanese scientists had anticipated radiation sickness. Within weeks of going to Hiroshima, all of Fuchida’s colleagues had died of radiation sickness. Only Fuchida did not succumb.

Afterwards, returning to his family’s chicken farm he recalled, ‘Life had no taste or meaning… I had missed death so many times and for what? What did it all mean?’ He was soon to find out. Having been called to testify at the Tokyo War Crimes tribunal as a witness, Fuchida became infuriated by what he perceived as ‘Victor’s justice’. Surely, he asked, Americans had treated their POWs as badly as the Japanese?

He thus set about finding Japanese captives. To his astonishment he found that they had been well treated. He was particularly struck by the tale of a former comrade who Fuchida had thought had died at the Battle of Midway. This survivor recalled the compassion of a Christian woman called Peggy Covell, who had treated him and his fellow Japanese captives with exceptional kindness even though her own missionary parents had been murdered by the Japanese army in the Philippines. The episode sparked his curiosity about Christianity. In September 1949 he converted. ‘Looking back,’ he said later, ‘I can see now that the Lord had laid his hand upon me so I might serve him.’ He later wrote a book called, From Pearl Harbor To Calvary (1959).

Fuchida spent much of his remaining life in the United States where he toured the country as a member of the Worldwide Christian Missionary Army of Sky Pilots. On one such tour he met Paul Tibbets who had flown the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, Enola Gay, which had dropped the atom bomb, ‘Little Boy’, on Hiroshima. ‘You did the right thing,’ Fuchida told Tibbets, ‘You know how fanatical they were… they’d die for the emperor… Can you imagine what a slaughter it would be to invade Japan?’

Fuchida turned out to be a rare critic of his country’s participation in the conflict and a supporter of the use of a US atom bomb to end it. Another rare Japanese adherent of this position, nuclear scientist Masa Takeuchi, concluded that ‘If we had built the bomb first, we would have used it. I’m glad in some ways that our facilities were destroyed.’

Fuchida’s views starkly contradicted the standard narrative in the school texts approved by today’s ultranationalist Japanese government, (and revisionist US historiography) which lay the blame for the war almost entirely on the West. Fuchida’s maverick views were in keeping with what was a remarkably unusual life.

Comments