Bad figurative painting is today’s hottest trend. Last autumn Artnet listed the top ten ‘ultra-contemporary’ artists (meaning those born after 1974) with the highest total auction sales so far that year. Counting down: Lucas Arruda, Jia Aili, Ayako Rokkaku, Dana Schutz, Amoako Boafo, Nicolas Party, Matthew Wong, Jonas Wood, Eddie Martinez, Adrian Ghenie. None are household names. All are figurative painters, though some play with bad abstraction as well. None are particularly exciting. Many, many others are climbing after them.

Since the list was published, Dana Schutz’s ‘Elevator’ (2017) sold for nearly £4.8 million at Christie’s Hong Kong, a new record price for the artist. The work is a poor impression of cubism. A century after Duchamp’s ‘Nude Descending the Staircase, No. 2’ (1912), Schutz paints people in clothes fighting in an elevator. She’s also painted ‘Trump Descending an Escalator’ (2017) in the style of early-20th century German expressionism, which went for £688,000 at Phillips last year.

It’s been clear for a while that art’s running out of ideas. Back in 2014, the critic Walter Robinson coined the term ‘zombie formalism’ to describe a trend for market-friendly abstract painting that took the dead formalist aesthetics of mid-century abstract expressionists and brought them halfway back to life. It was soulless, going through the motions, and had nothing new to say. ‘In our postmodernist age,’ wrote Robinson, ‘“real” originality can be found only in the past, so we have today only its echo.’ Young, ambitious painters looked for original ways of making copies, such as Jacob Kassay and his electroplating process, or Lucien Smith and his fire extinguisher filled with paint. For a brief moment their prices went up like an inferno, before falling away more slowly like ashes. It’s taken only a few years for a zombie figuration movement to rise up from the graveyard of art history and take their place.

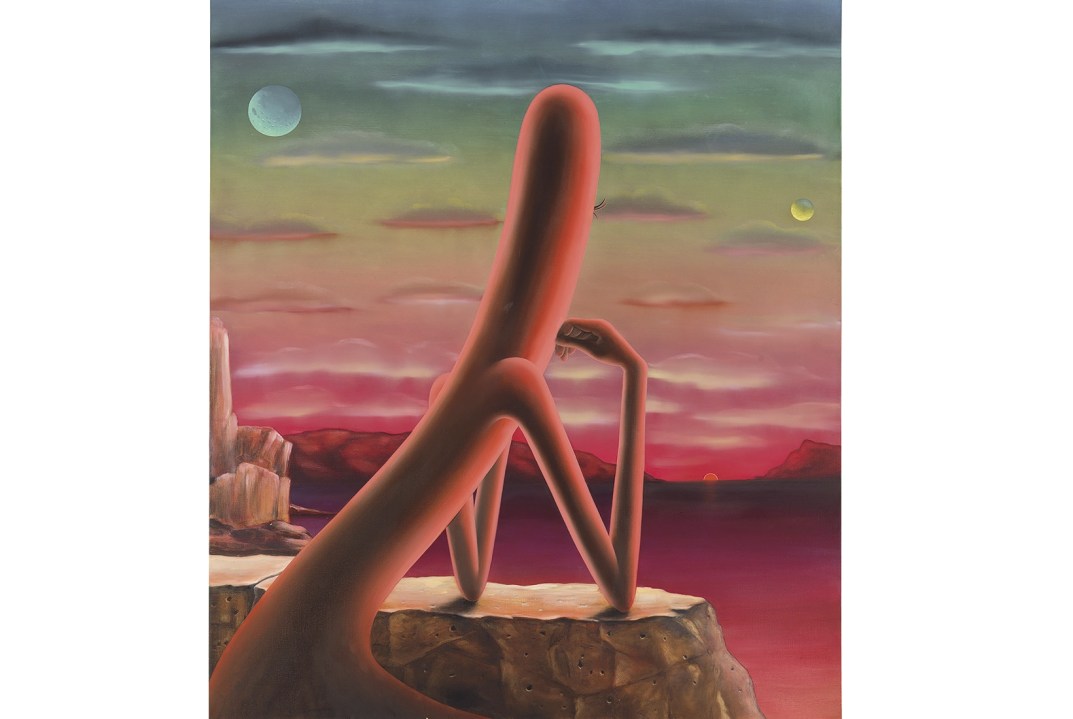

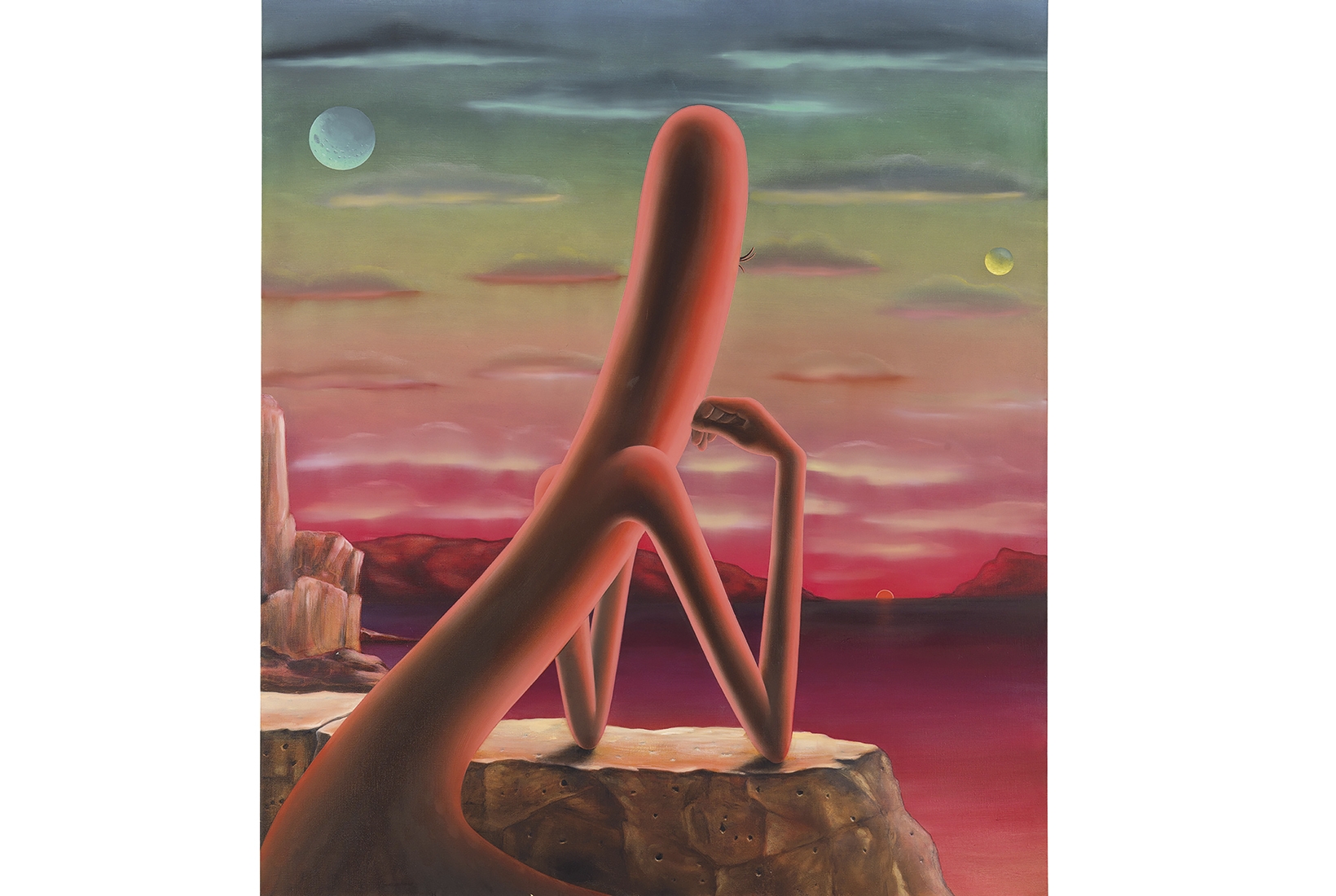

Today’s bestselling figurative painting is all stylistic gimmicks and new ways of remaking the classics. Adrian Ghenie paints Van Gogh’s ‘Sunflowers’ in the style of Francis Bacon. ‘Emily Mae Smith,’ noted Alex Greenberger, in his essay on zombie figuration last summer, ‘has gotten an unlikely number of artworks out of no more than recreating famous paintings with the human subjects replaced by broomsticks.’ Her ‘Alien Shores’ (2018), which sold for a record £277,200 at Phillips last autumn, shows a broomstick gazing wistfully at a cosmic sunset under twin moons. It’s the first-ever portrait of a household cleaning object experiencing saudade. Edward Hopper meets Space Odyssey meets Homebase. Julie Curtiss, whose work fetched a record £292,000 at Christie’s New York in winter 2019, paints in a similar manner, but rather than broomsticks, her imaginary world is full of people and objects made of coiffured, glossy brown hair. Ewa Juszkiewicz, who recently joined the all-powerful Gagosian Gallery, paints 18th and 19th century-style European aristocratic portraiture with a twist: faces are obscured by hair — again — or by plants, satin or tribal masks. I see dead people; with knickers on their face.

These paintings belong to and assume the logic of the feed: designed to be apprehended in under five seconds

Such quirky, esoteric mash-ups feel less like stylistic innovations and more like branding exercises, reflecting a present in which one’s ability to market oneself is more important than mastering a craft or coming up with fresh ideas. As critic Sean Tatol recently noted for the Manhattan Art Review: ‘Like late Mozart, artists are often only concerned with superficialities such as aesthetic ornament or self-branding and have little to no consideration of the formal qualities that actually matter.’ There’s a lack of new ideas in art, and so slipshod and incoherent bootlegs of worn-out aesthetics are revived and presented once more as the next big thing. The canon is reimagined with twists, in paintings with the uncanny appearance of having been designed by algorithm and made by Snapchat or Instagram filter. They occupy the bardo between content and art. They belong to and assume the logic of the feed: they’re designed to be fully apprehended in less than five seconds. They’re not images of reality so much as images of paintings, bled of affect. As this approach keeps selling, the art world keeps churning it out. Figurative painter go brrr.

While zombie formalism came and went quickly, and was a relatively small trend, zombie figuration is a global phenomenon. There’s just so much of it. It keeps coming in tiresome, undead waves, traipsing through the apocalyptic 2020s. Its power resides in its lifeless multiplicity. Bad figurative painting is everywhere. It crawls into every room, from museums to galleries, to cool young project spaces, to the world at large. Former president George W. Bush is a bad figurative painter now. Hunter Biden was, notoriously in art circles, painted naked by a London-based terrible painter. The most expensive painting in history, Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Salvator Mundi’, which was authenticated in 2008, in a studio above the National Gallery, as his lost masterpiece, and sold at Christie’s New York in 2017 for £342 million, has been heavily restored and looks awful. Christ’s face is too big. Conservators have moved his eyes to the wrong place. Even the saviour of the world has become a clumsy copy, another bad figurative painting. In today’s exhausted moment mediocrity can thrive as never before.

The oldest critique of modern art in the book is to say: ‘My child could make this.’ Usually this refers to a sloppy, high-concept piece. Most bad figurative painting is the opposite: these are technically proficient paintings lacking in world-views or provocations. They don’t look like they were painted by children; they look like they were conceptualised by children to please other children.

Street artist turned market darling Kaws remakes pop-cultural staples in his own comic style. In spring 2019 he shocked the art establishment, and changed the game, when his painting ‘The Kaws Album’ (2005), a remake of The Simpsons’ remake of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band cover, was sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong for £10.9 million on April Fools’ Day.

By November that year, Christie’s Hong Kong had jumped on this latest trend and given it a name, organising ‘Hi-Lite’, a 16-lot sale of Asian and Western artists working with cartoon forms and kitsch pop aesthetics: Kaws, Yoshitomo Nara, Takashi Murakami and Pharrell Williams, Mr., Madsaki, Erik Parker, Nicolas Party and Alex Israel.

‘Hi-Lite’ is high art for people who don’t like complicated ideas; people who, when they’re watching a cartoon, begin to wonder if they might be inside the cartoon. Ivanka Trump and Jared Kushner keep a large portrait of Alex Israel’s head hanging over their breakfast table. It’s art that’s easy to apprehend and enjoy, and also to post. ‘Lite’ is for light, but also for literal. It’s the bimbofication of art.

Bad figurative painting is a renunciation of art’s radical avant-garde potential, but also of traditional ideas of sublime and transcendental beauty. It’s polite, unremarkable, middle of the road. Pleasant enough, but mediocre at heart. Nice but dim. As such, it’s an apt example of what blogger Venkatesh Rao described in 2017 as today’s ‘premium mediocre’ lifestyles: ‘Mediocre with just an irrelevant touch of premium, not enough to ruin the delicious essential mediocrity.’ The examples he gave included ‘cupcakes and froyo… cruise ships, artisan pizza, Game of Thrones, and the Bellagio’.

In the 1980s, German artists such as Martin Kippenberger and Albert Oehlen, joined in the 1990s by Britain’s Merlin Carpenter, played with ideas of bad painting in an ironic and knowing fashion, looking to challenge the status quo by making paintings that were even more dumb and meaningless than everyone else’s, but bad painting has now become the status quo. If painting badly was once a punky bohemian nihilist mode, it’s since been incorporated as a sign of earnestness, integrity. Today’s bad figurative painting is inoffensive by nature, unambitious in technique, and dreadfully earnest, and it’s this total inoffensiveness and lack of ambition or edge that makes it so frustrating, and, for me, dispiriting. Its ubiquity, its decorative quality, and the ridiculous prices it commands only make the nausea worse. If I’m so clever, and these painters so foolish, how come they make more in a morning than I do in the year? Who’s the real idiot?

What does it mean, this rotten painting? The earliest figurative paintings in the caves were likely a form of hunting magic. In ancient Greece, artworks were representations of ideal forms. Later came celebrations of the glory of God, and the beauty of man, and modern explorations of perception and the subconscious, and pop art, and postmodern experiments in appropriation and irony, and conceptual gestures. But what painting does now is unclear. Jonas Wood paints plants and vases. Josh Smith paints empty streets during lockdown. These are paintings of nothing. Watered-down, cordial, dull subjectivities. There’s so much figurative painting, so little abstract thought.

Just as socialist realism produced accessible images of contented lives under communism, today’s figurative paintings reflect the banality of modern life without passion or criticality. They’re manifestations of the triumph of literalness in society: a desire for relatable images with everyday subjects that remind us of our own lives. All culture has been tending towards shallow content lately. Hi-Lite gives us cartoons that are also paintings, just as Hollywood gives us superhero movies instead of cinema, just as publishing houses give us Young Adult fiction in place of literature. We’re served Instagram-friendly cultural objects that anyone could come up with and anyone can understand without thinking. It’s zombie entertainment. It’s ‘Let people enjoy things’ culture. Don’t let people enjoy things. Enjoying things has brought us to the edge of the abyss. What we could do with instead is more challenging and unconventional painting.

Comments