Early in the 16th century, Fra Bartolomeo painted an altarpiece of St Sebastian for the church of San Marco in Florence. Though stuck full of arrows, the martyr was, according to Vasari, distinctly good-looking in this picture: ‘sweet in countenance, and likewise executed with corresponding beauty of person’. By and by the friars of San Marco discovered through the confessional that this image was giving rise to ‘light and evil thoughts’ among women in the congregation.

It was removed and eventually sold to the King of France (who was presumably less bothered by that sort of thing). So even during the heyday of Michelangelo and Raphael depictions of human bodies without any clothes were not necessarily all about art. This is one of the themes of The Renaissance Nude, a truly marvellous exhibition at the Royal Academy.

This show is packed with lovely things to look at. There are beautiful bodies aplenty, and the roster of artists includes many of the great names in painting and sculpture — Dürer, Titian, Raphael, Signorelli, Memling. As a visitor, that’s really all you need to know.

Those reading the hefty catalogue, however, will discover that this is a display with a thesis. Sixty or so years ago, Kenneth Clark, of Civilisation fame, made a famous distinction between the naked and the nude. The exhibition aims to qualify and complicate this venerable analysis.

The nude, Clark argued, was invented by ancient Greek sculpture, and then revived at the Renaissance. However no living person actually looked so poised and perfectly proportioned as the figures in Perugino’s painting of Apollo listening to his protégé, the flute-playing shepherd Daphnis, c.1495.

In landscape and poetic mood this little panel is what Oliver Goldsmith called ‘the pink of perfection’ — even if god and flautist are both as brown as you’d expect of someone who went around undressed in a Mediterranean climate. But it’s not exactly naturalistic. According to Clark, the truth about humanity in the buff is much closer to King Lear’s ‘poor, bare, forked animal’.

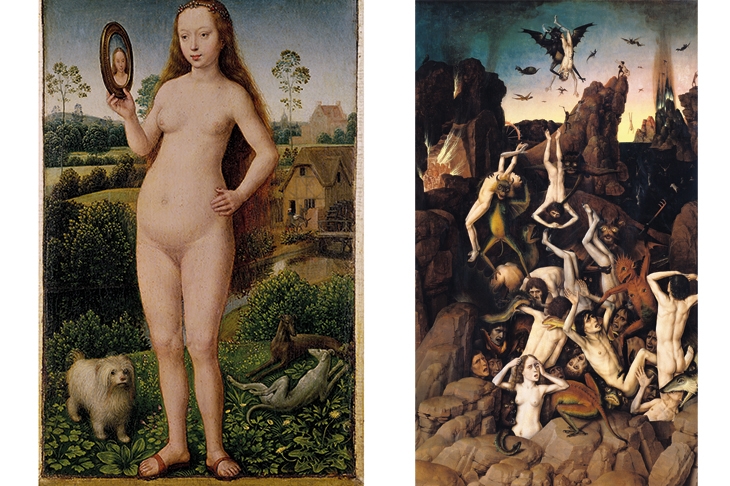

Clark also claimed that northern artists had a lot of trouble with the Italian notion of the nude, but were strong on the ‘bare, forked’ reality. When contemplating two superb panels of the blessed entering paradise and the damned tumbling into hell by the Netherlandish painter Dirk Bouts, it’s easy to believe that Bouts had looked hard at genuine bodies — especially when portraying the sinners — since the blessed have sheets to cover their shame. These ungainly physiques are just what you might see at a nudists’ colony, and precisely what Albrecht Dürer presented in his print of men washing in a public bath.

But what, you might wonder, about the other gender? The exhibition team agree that the ideal male nude was an Italian forte, but go on to point out that the unclothed female was a northern, particularly French, speciality.

Miniatures on show from 15th-century French and Flemish manuscripts do imply a late medieval interest in pictures of ladies in the altogether. Unfortunately, though, a lot of the art-historical evidence has been destroyed by prudes. Pictures of women bathing by Van Eyck and Van der Weyden, once famous, vanished long ago.

It seems from the evidence on display that 15th-century northern artists took an interest in naked woman — certainly much more than the Florentines, who were fixated on naked men — but also that they were hazy about what female bodies actually looked like. Hans Memling’s ‘Vanity’ (c.1485–90) is a beguiling picture, but anatomically hopeless.

This might have been caused by a practical difficulty. It was easy enough to ask a studio assistant to take off his doublet and pose, but woman models were hard to recruit in Renaissance Europe. The main exceptions to this rule seem to have been Venice — where Titian clearly had real models for his Venuses and nymphs — and Germany, enthusiastic about naturism then as now. Dürer was perhaps one of the first artists to draw a living, undressed woman, although — a point to Lord Clark — he was visibly much better at middle-aged and overweight bodies than the classical goddess type.

Of course, not all the art of the period was concerned with Greek mythology. Many Renaissance nudes — martyrs, Adam and Eve, risen souls, suffering Christs — were made for Christian churches. In the exhibition the ‘St Sebastian’ by Cima da Conegliano (c.1500), with soulful expression and scanty loincloth, gives an idea why Fra Bartolomeo’s altarpiece might have led the congregation astray (see p29).

This combination of the sacred and the stripped troubled pious prelates. Several popes considered obliterating Michelangelo’s Sistine frescoes; little furry jockstraps and wisps of cloth were actually added to his ‘Last Judgment’ in the name of decency. Since then the proponents of the nude as art (and not depravity) have generally won their point. On the other hand, in this age of #MeToo the subject is still controversial. Perhaps it always will be.

Comments