The discriminating Argentinian novelist Jorge Luis Borges once revealed his fondness for ‘hourglasses, maps, 18th-century typography, etymologies, the taste of coffee, and the prose of Stevenson’ – a list that was quirky and eclectic, adjectives that neatly encapsulate Robert Louis Stevenson himself.

The story has often been told – but it’s a good one – of how the wiry, velvet-jacketed Stevenson emerged from Edinburgh’s haute bourgeoisie to become a hugely successful writer, before ending his shortish, sickly life on the Pacific island of Samoa in 1894, a revered expatriate married to a wilful American woman a decade his senior.

Leo Damrosch, a literature professor at Harvard, offers no special sparkle, but he knows his stuff (notably unpublished drafts of Stevenson’s writing); he synthesises well; and he arrives at a thoroughly satisfying overview of his subject’s life and work.

Louis – pronounced Lewis, his given birth name – made things easy for biographers by being not just prolific but also engaging in most things he wrote and did. His childhood was spent in the shadow of his high-achieving family the ‘Lighthouse Stevensons’, whose ingeniously engineered flashing beacons saved countless lives in remote Scottish waters.

In the nursery his nanny ‘Cummy’ nurtured his romantic Scottish nationalism. His first book, written when he was 16, was a history of the Pentland Rising, the Covenanters’ revolt against English hegemony in 1666. Having had the text privately printed, his father later destroyed every copy because he regarded the style as too novelistic and sympathetic to the underdog. The cussed lad took note and transferred these features to works such as Kidnapped and Catriona.

At Edinburgh University he initially toed the parental line, studying engineering and then law. But, having discarded his Presbyterian religion, he preferred bars to lecture halls. As a friend remarked, he had ‘all the luxuries of a privileged existence but no sense of freedom’. His life there-after was spent on the move, in search of that illusory goal.

As an aspiring writer, he was fortunate to meet several leading figures who promoted his career. Visiting a cousin near Cambridge in 1873, he was introduced to Sidney Colvin, the Slade professor of fine art, and Frances Sitwell, Colvin’s married mistress, soon to be his wife, to whom (to complicate matters) Louis poured out his heart in impassioned correspondence. Colvin, who later produced a bowdlerised edition of Louis’s letters, opened many doors, including sponsoring his election to the bibliophile Savile Club. He commended his friend to Leslie Stephen, the editor of the Cornhill magazine, who commissioned essays and stories from the young Scotsman, starting in 1874 with a study of Victor Hugo. Louis was fortunate to live in the heyday of serious literary journalism, since essays were his particular forte.

Through Stephen he met W.E. Henley, another robust editor, who was in Edinburgh trying (successfully) to save his right leg from amputation (the left had already gone from a tubercular condition). Henley would become the model for Long John Silver in Treasure Island. In his Scots (later National) Observer he advocated a virile approach to fiction which prioritised the spirit of adventure over the moralising domesticity associated with George Eliot. External forces regarding character development were deemed more important than internal. Louis took naturally to this form, which became known, perhaps confusingly, as romance.

Having discarded his Presbyterian religion, Louis preferred the Edinburgh bars to its lecture halls

It was hardly a historical accident that this type of romance – whether set in the Highlands, the Caribbean or (in Rider Haggard’s novels) Africa – coincided with British overseas expansion. Louis generally averted his eyes from any imperialist context, though tensions between settlers and natives added a Conradian touch to later works such as The Beach of Falesá and The Ebb-Tide.

Louis often travelled to France, where he was attracted to the bohemian lifestyle of his painter cousin Bob Stevenson. At an artists’ colony in Grez-sur-Loing outside Paris he met the American Fanny Osbourne, whom he chased back to California and married once she had unhitched herself from her ne’er-do-well husband.

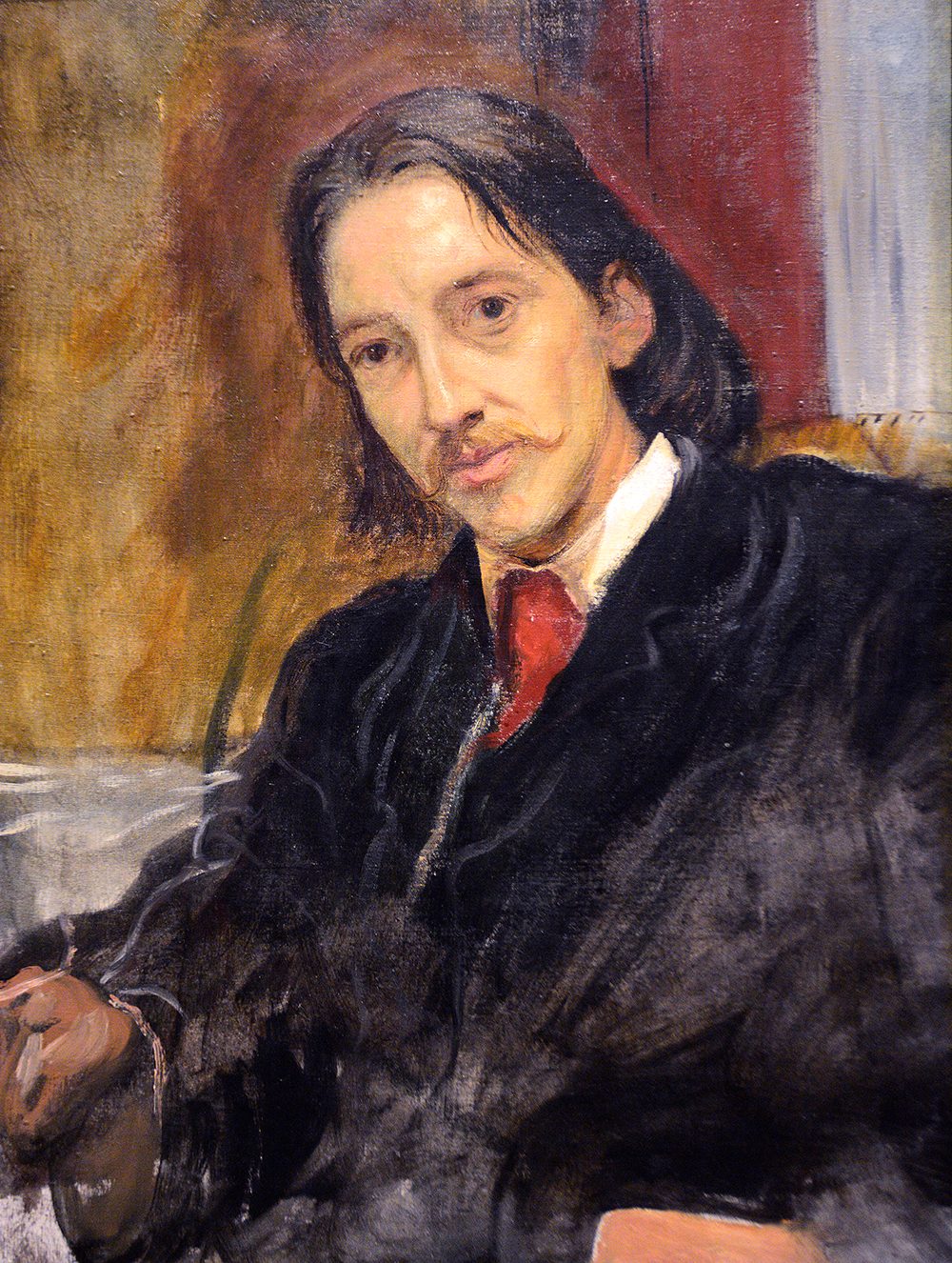

An artist friend of Bob was John Singer Sargent. Later, when Louis and Fanny were becalmed in Bournemouth, Sargent painted a remarkable joint portrait, showing husband and wife at different sides of a Burgundy-coloured room. Lanky Louis is moving in sprightly fashion to edge out of the picture, while Fanny, colourfully attired in a sari, sits implacably on a chair. It conveys all one needs to know about Louis’s restless energy and need to escape restrictions. Yet the marriage endured. Fanny became Louis’s trusted collaborator and often co-writer. Plagued by weak lungs, he was often unwell. Yet his travels – on a donkey in the Cevennes, with Fanny in the Adirondacks and Californian sierras, and eventually across the Pacific to settle in Samoa – make for gripping reading.

His break-out novel, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, in 1886, was unusual for being more horror than adventure story. It explored the nature of good and evil – a recurring theme, along with justice. There were also lesser works, such as Prince Otto, a historical thriller admired by Vladimir Nabokov. Its flirtatious heroine Countess von Rosen was described by Louis to Henley as a ‘fuckstress’ – an unusual word at any time, but in keeping with a man who declared ‘the damn thing of our education is that Christianity does not recognise and hallow sex’.

Yet he doesn’t seem to have strayed from his marriage vows. On Samoa, where he was known as Tusitala, the Teller of Tales, he and Fanny lived contentedly on an estate in the hills above Apia, the capital. He became a trusted counsellor to often warring islanders whose political causes, including independence, he advocated in the pages of the Times. At the time of his death he was working on Weir of Hermiston, a novel often described as an unfinished masterpiece. In a bizarre creative appropriation, this title inspired a Jack Bruce song on his 1969 album Songs for a Tailor. But it was typical of the enchantment that Louis wielded across generations and genres.

Comments